IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps)

IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps)

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) is a U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) that seeks to fulfill Tehran’s ambition to become the Middle East's dominant political and military power. Iran’s hegemonic aims are detrimental to U.S. national security interests and regional stability. To understand the threat this transnational organization poses to U.S. interests, this resource first highlights a few events shaping the IRGC’s transformation from a hastily-organized militia into the Islamic Republic’s dominant military institution, responsible for exporting the Islamic Revolution abroad and protecting it from opponents at home. This resource also introduces the IRGC’s organizational structure and leadership before considering how each of the six core branches—the Basij, the Ground Force, the Navy Force, the Aerospace Force, the Intelligence Organization, and the Quds Force—advances Tehran’s internal security and foreign policy priorities. This report will provide an account of the commander of each branch, followed by the branch’s historical background, domestic activities, role in national defense, and foreign deployments. Finally, it looks at Khatam al-Anbiya Construction Headquarters, an economic conglomerate and a main source of funding for the IRGC.

- Type of Organization: Military, terrorist, transnational, violent

- Ideologies and Affiliations: Islamist, Khomeinist, Shiite, state actor

- Place of Origin: Iran

- Year of Origin: 1979

- Founder(s): Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini

- Places of Operation: Global, concentrated in the Middle East

Historical Background

On May 5, 1979, the founder of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, ordered the formation of the IRGC (Sepah-e Pasdaran in Persian) out of approximately 700 revolutionaries that were trained in Lebanon. From the early years of the Islamic Republic, which was proclaimed by Khomeini in April after his victory in a national referendum, these revolutionaries acted in accordance with their mission as stated in the preamble to the 1979 constitution. Specifically, they formed an “ideological army,” defended the country’s frontiers, and grew into an aggressive military institution devoted to “the ideological mission of jihad in God’s way.”

Moreover, the group controls extensive economic assets across all major sectors of Iran’s economy, though the total value of this portfolio is not publicly known. It also enforces conservative social rules, such as the mandatory hijab, as an auxiliary to the so-called Morality Police, a unit in Iran’s Law Enforcement Forces (LEF) dedicated to monitoring compliance with Islamic laws and responsible for enforcing rules in particularly brutal and violent fashion. The Morality Police was holding Mahsa Amini in its custody when she was killed, sparking the Woman, Life, Freedom movement in September 2022, against which the regime has deployed its security forces and agents, leading to the death of over 500 individuals in connection with the anti-regime movement, the most significant threat to the regime since its 1979 founding.

The newly-formed paramilitary was, at first, intended to serve as a check against a potential coup d’état attempt by the Army, which Supreme Leader Khomeini and his loyalists viewed with deep suspicion due to its ties to the former Pahlavi monarchy. Counterrevolutionary groups, such as the People’s Mujahedeen of Iran (MEK), also posed a threat to the regime, but the IRGC was able to suppress their resistance to the direction of the Revolution. And, critically, the IRGC asserted Tehran’s control over the country’s borders, conducting a brutal counterinsurgency against Kurdish separatist groups in 1979-1980.

The most important role served by the IRGC in the early years of the Revolution, though, was to defend Iran against an invading Iraqi army. Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Iraq, designed to thwart the Revolution from metastasizing in the region, gained the support of most Western powers, including the U.S. and Europe, leading to a two-year Iraqi offensive that met with little success.

In the spring of 1982, Iran repelled Saddam’s forces and attempted to press a counteroffensive into Iraq that dragged the war into a stalemate for another six years. The Iran-Iraq War, which came to be known to IRGC commanders as the “Sacred Defense,” is known for its brutality and high death toll, and transformed the IRGC into a more classical and effective military institution, while appearing to prove the mettle of the IRGC’s pious and revolutionary values.

After the war, battle-tested IRGC officers ascended to the top military and security posts in the Islamic Republic and established a stranglehold over the economy. This process continued after the Assembly of Experts selected Ayatollah Ali Khamenei as the supreme leader in June 1989. From key positions and often acting at the behest of the supreme leader, the IRGC swayed political decision-making in the other branches of the elected government. On one occasion, senior IRGC commanders threatened a coup d’état if then President Mohammad Khatami did not take a more forceful stance against anti-regime student protesters in 1999. Then commander of the Quds Force Qassem Soleimani, and its current commander Esmail Qaani, along with other IRGC top brass signed onto this letter, staking out their positions as Khamenei’s lieutenants, who would take action against the populace and the elected state if either threatened the revolutionary regime.

The IRGC also acquired extensive financial stakes in all major sectors of Iran’s economy in part because of its political clout. During the presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013), the IRGC received a succession of huge no-bid government contracts, leading to an expansion of its economic portfolio.

Additionally, the IRGC also became a dominant force in social contexts. The Basij militia promoted and enforced the Islamic Republic’s severe interpretation of the Quran throughout Iranian society using violence and intimidation. The IRGC thus became a dominant political, economic, and social institution, indispensable to protecting and extending the Islamic Revolution and preserving Khamenei’s supreme leadership.

Organizational Structure

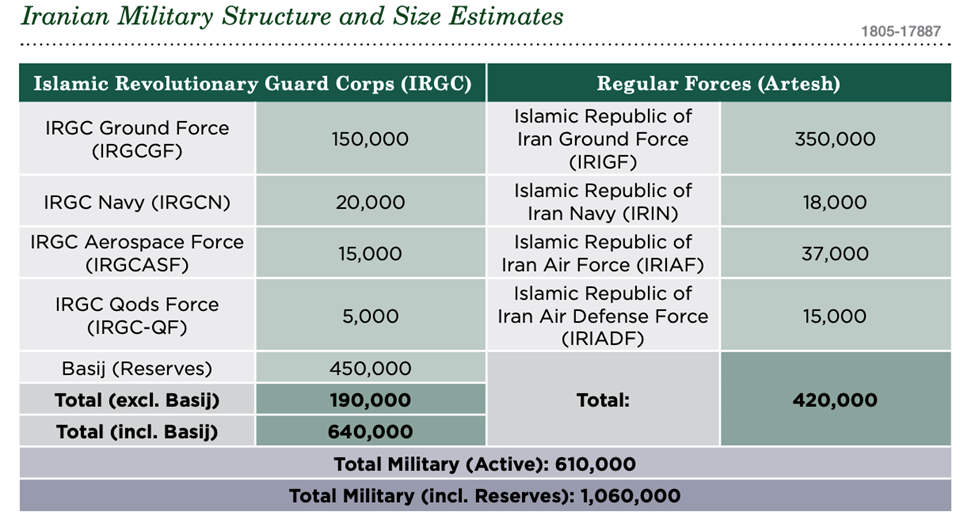

The Iranian military structure remains bifurcated to this day, with the IRGC continuing to receive preferential treatment from the supreme leader. The IRGC today exercises influence that dwarfs the Army (Artesh in Persian). However, it does not answer to the president. It answers directly to Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, the commander-in-chief. He has final authority on all matters of religion and state, according to the Islamic Republic’s foundational doctrine: velayat-e faqih. The supreme leader appoints the overall IRGC commander and installs clerical representatives in each of its branches to ensure their revolutionary character The Armed Forces General Staff, dominated by IRGC commanders, administers the IRGC, Army, and national police.

The top commander of the IRGC, Major General Hossein Salami, and his six branch commanders oversee the implementation of the IRGC’s mandate. According to Iranian law, the IRGC’s purpose is “to protect the Islamic Revolution of Iran and its accomplishments, while striving continuously…to spread the sovereignty of God’s law.” To these ends, the IRGC combines conventional and unconventional military roles with a relentless effort to pursue and punish domestic dissenters. Salami believes violence is justified as an instrument to impose conservative Islamic law and suppress opposition movements. He claims that the U.S. should be evicted from the Middle East, and the “Zionist regime” wiped off the map. The other IRGC commanders parrot similar statements, reflecting the goals that drive this hyperaggressive institution.

In 2007, the U.S. government designated Salami as a weapons of mass destruction (WMD) proliferator while he was in charge of the IRGC’s missile program as commander of the IRGC’s Air Force (later renamed Aerospace Force). Salami replaced Mohammad Jafari in 2019 as the overall commander, two weeks after the U.S. designated the IRGC as an FTO. The U.S. has not designated Salami based on his human rights crimes, despite the Basij’s and Ground Force’s killing of protesters while he was in office in November 2019. The E.U. designated him for human rights abuses in 2021, citing his responsibility for this use of lethal force. In November 2022, the E.U. levied additional sanctions against Salami for overseeing the provision of Iran-made unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to Russia for use in its war against Ukraine. Before becoming commander-in-chief of the IRGC, Salami served as deputy commander-in-chief, and prior to that, commander of the IRGC’s Aerospace Force.

The Basij

The office of the commander of the Basij oversees and deploys one of the regime’s most important resources: an abundant, loyal youth following. The first part of this section introduces the Basij commander. The second part discusses the Basij’s first major role in the history of the Islamic Republic, namely defending the country’s frontiers in the Iran-Iraq War. The final section covers the Basij’s recruitment, training, law enforcement, and business operations; and its role in national defense and foreign military operations.

The Basij Commander: A Dedicated Human Rights Abuser

Brigadier General Gholamreza Soleimani—a U.S.- and E.U.-designated human rights abuser in charge of the Basij when it massacred peaceful Iranians protesting abrupt gas price increases, repression and corruption in November 2019—commands the volunteer paramilitary. Previously, he served as commander of the Saheb-Al-Zaman Provincial Corps in Esfahan Province. While there, he hailed the need for the formation of a resistance economy for development and lashed out against the then-Rouhani government. Like most other IRGC commanders, Soleimani assumed his post with a commitment to the regime’s hegemonic aspirations. However, his branch focuses on maintaining internal security, more than promoting outward expansion. He professes that Iran’s unique democratic system of government with spiritual elements should serve as a model of governance for other countries. In this view, the pursuit of hegemony is not only achieved by way of force, but also by the supreme leader’s interpretation of Islam, which is the foundation of the Islamic Republic’s system of government.

Historical Background: The "Sacred Defense"

The charismatic Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini created the Basij in November 1979 as a militia made up of his pious youth followers—some of whom had fought against the Shah—to help manage property confiscated from the former elite and royal family. Much of the wealth seized in the revolution was supposed to be redistributed to lower-class families, but the Basij soon found itself in another role when Saddam Hussein’s army invaded, attempting to seize territory amid the post-revolution instability. The supreme leader’s call for the creation of a “twenty-million-man-army,” though never realized did foretell an effective mass mobilization effort in response to the invasion.

The ranks of the Basij swelled as hundreds of thousands of Iranians volunteered to fight in the Iran-Iraq War in the name of the nascent revolutionary government and its supreme leader. Of the 300,000 Iranians killed in action, loyal Basijis—as members of the Basij are called—died at staggering rates. Often undertrained, if trained at all, Basijis were “martyred” in so-called human-wave offensives in which they unwittingly swept minefields with their bodies and sought to overwhelm enemy forces by rushing into machine gun fire and artillery without support. Infamously, young children were sent to die in these horrific attacks, which proved to be an effective means of repelling Iraq in mid 1981.

The Basij’s sacrifice in the war contributed to its leadership’s belief that they should assume key miliary and security posts in the Islamic Republic. Notwithstanding ambitions to operate the paramilitary organization autonomously, the Basij was brought under the command of the IRGC chief in 2007, and then incorporated into the IRGC’s Ground Force in 2009 after its poor performance in suppressing the “Green Movement,” a protest movement opposed to electoral manipulation in the reelection of hardline conservative figure Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Ahmadinejad’s presidency (2005-2013) led to the empowerment of the Basij and an expansion of its domestic mandate; the Basij was called upon to exert greater social and moral control over society. Basijis were elevated to key government and security posts during this period, and the Basij’s budget increased drastically. President Ahmadinejad, a former member of the Professor Basij Organization, allocated many cabinet seats to professors from this organization. They subsequently purged university leadership and installed more conservative figures, who were deeply opposed to western academic influences and culture.

As the Basij enforced religious precepts more strictly, it became increasingly viewed as a partisan actor, part of the fraudulent reelection of Ahmadinejad, and responsible for the implementation of his policies. The Basijis were also correctly seen as brutal enforcers deployed against the “Green Movement.” What was once a disorganized group of young fighters serving as cannon fodder had become a vigilante terror squad known for using iron bars, clubs, truncheons, chains, and firearms, against protesters.

However, the Basij did not effectively quell the “Green Movement.” In some cases, local Basijis failed to attack their fellow citizens, particularly if they saw them expressing their piety with loud proclamations that “God is great.” Nevertheless, the attacks on dissidents continued. Wikileaks reported in 2010 on an eyewitness account from inside a Basij camp of the use of sadistic forms of torture against dissidents, including crushing people to death and disembowelment. Amid the overall failure to suppress the movement, then-Basij commander, Hossein Taeb, was removed from his post. He was later made the head of the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization.

The Basij's Functions: Internal Security and National Defense

The Basij fulfills several internal security and national defense functions. The first, and arguably most important is recruitment for public service. The Basij oversees a vast recruitment network that penetrates all segments of society. Typically, poor, uneducated, young, and devout Shia are targeted in this campaign with promises of upward mobility. They are enticed by a small stipends, loans, housing, welfare, and pilgrimages. The Basij members are also allowed to bypass mandatory conscription; they are provided with preferential university placement; and sometimes promoted to military and security posts. The Basij also offers technical training, which is appealing in underdeveloped areas.

Basij members run clubs, known as Paygahs, at virtually every mosque across the country, and use religious studies and recreational activities such as sports and field trips to lure potential recruits. The underlying aim of these programs is to build a loyal political constituency, whose average age and strong religious beliefs are meant to guarantee the longevity of the Islamic Republic.

Today, there are approximately 450,000 active reservists in the Basij, and hundreds of thousands more who are inactive but mobilizable. Estimates of the total number of active members run as high as three million, with an average age between 15 and 30 years old.

Once recruited, Basij members are trained in ideology. Manufacturing an enemy whose existence represents a threat to the survival of the Islamic Republic is central to indoctrination. The existence of an external threat is essential to any revolutionary regime because it provides legitimacy and a higher purpose for existing. That enemy, of course, is the United States, also known as the “Great Satan,” and its partner Israel, known to the IRGC as “Little Satan.”

Domestically, the Basij carries out a grassroots campaign to counter influences that are opposed to the regime. This insidious campaign depends not only on brute force, but also Basij presence in all areas of society; its members are well-organized and represented at schools, workplaces, factories, mosques, and every major public institution. They work as recruiters and proselytizers and spy on and harass critics, dissidents, intellectuals, bloggers, and activists. On university campuses, they organize against leftists, reformists, traditional (less radical) conservative groups, and student unions. At workplaces, they bust strikes, with branches devoted to countering unions and professional organizations.

The Basij also operates as an auxiliary law enforcement unit deployed—sometimes alongside the IRGC’s Ground Force—to support the Law Enforcement Force (LEF) in times of acute crisis at home, entrusted to employ violence against fellow citizens. They shot and killed hundreds of protesters in 2019 and have deployed to suppress the Mahsa Amini protests, armed with anti-riot weapons such as tear gas, pellet-loaded shotguns (“Birdshot”), and paintball guns, riding on motorcycles and pickup trucks. Basijis often carry out their abuses and destroy vehicles and property without showing any government identification, reportedly to afford the regime some degree of plausible deniability.

As an auxiliary law enforcement unit, the Basij also serves alongside the so-called “Morality Police,” a unit under the LEF that pursues and punishes women and men for transgressions against conservative Islamic law. Like the “Morality Police,” which was responsible for beating Mahsa Amini to death, the Basij often target and brutalize women for removing the compulsory hijab. To the regime, the hijab and mandatory gender segregation in public places, are a bulwark against decadence, corruption, and promiscuity associated with Western infidels.

Moreover, the Basij polices relationships, opposing same-sex behavior and certain dating practices, and enforces bans on some types of music, movies, and art—especially those with Western influences. Alcohol and drug use, theft, and other criminal activity, including the use of satellite antennae, also fall under its purview.

Though some are motivated by materialistic interests, Basijis tend to be true believers in the view of Islam as put forward by clerical figures in the regime and in particular the highest religious leader, the supreme leader. They are like the ruling party of an authoritarian government, working to amplify pro-regime propaganda and organize pro-regime rallies and religious ceremonies, which invariably call out the “Great” and “Little Satan.” They work with other suppression entities, such as Ansar-e Hezbollah, who in 2009 countermobilized against the “Green Movement,” advocating for the punishment of peaceful protesters whom they perceived to be seditious rioters and conspirators. By supporting the Islamic Republic, they contribute to the perception, however deceiving, of regime legitimacy. The Basij and the IRGC comprise the Islamic Republic’s core constituencies and political power base.

Less ideologically-driven Basijis also achieve their aims because the regime funnels wealth, power, and prestige into their ranks. The Basij conducts its economic activities through the foundation Bonyad Taavon Basij (“Basij Cooperative Foundation”), which receives preferential loan and tax treatment and government subsidies.

In 2018, the U.S. Department of the Treasury designated a vast financial network supporting the volunteer paramilitary, and assessed that the Basij held multiple billions of dollars-worth of assets in a network of shell companies in major industries, such as metals, minerals, automotive, and banking. The Basij owns at least 20 corporations and financial institutions, including Mehr Eqtesad Bank, a financial offshoot of Bonyad Taavon Basij that pays dividends and provides hundreds of millions of dollars-worth of interest-free lines of credit for Basij members, helping them to develop businesses. As the Basij became more wealthy and powerful, its brutality and oppression have generated a strong public backlash against its activities. The anger and resentment against the regime and its enforcers in response to Mahsa Amini’s death is only the most recent manifestation.

Another function served by the Basij is national defense. In the event of an invasion by a military power capable of quickly destroying communications and the command-and-control structure inside Iran, the Basij would be called upon to conduct asymmetrical warfare throughout the country. These operations would aim at thwarting an occupation and repelling the foreign power through attrition. If the Basij mounted an effective mobilization effort and its units dispersed throughout the country remained loyal to the Islamic Republic, a modern war in Iran could resemble the 2003 Iraq War in which the U.S. and coalition forces fought a domestic insurgency to establish a democratic form of government.

Although the Basij tends to serve domestic interests, in the context of the Syrian Civil War and Iran’s involvement in the fight against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), the Basij also supported foreign military operations. In 2018, the U.S. Department of the Treasury noted that the Basij had recruited child soldiers who later deployed to the Syrian battlefield. The Basij’s Imam Hossein Battalion—a light infantry unit trained in counterinsurgency tactics—offered support to the IRGC’s Ground Force in Syria at the height of the civil war. The Basij and IRGC officers also deployed to Iraq to coordinate the fight against ISIS, gather intelligence, and sometimes fight themselves.

Finally, it is notable that the Basij serves as a model for foreign militias, such as Lebanese Hezbollah, Iraqi militias, and the pro-Assad National Defense Forces (NDF) in Syria, in that it doubles as a social welfare provider and organizes cultural and religious events. The Basij uses social welfare to build a patronage network. In one such instance, the Basij sent medical practitioners to rural areas to provide care to sick people unable to afford treatment. The export of this model—more commonly known as the “Hezbollah model”—helps Tehran create spheres of influence. Iran-backed militias gain influence not only through the use of violence, but by organizing formidable constituencies and fielding candidates for government posts.

The Ground Force

This section begins with a brief account of the U.S. and European perspectives on the current commander of the Ground Force, Brigadier General Mohammad Pakpour. The second part includes a historical account of the Ground Force’s national defense doctrine, which is based on assumptions similar to those of the Basij. The third part covers the Ground Force’s role in internal security, national defense, and foreign military operations.

The Ground Force Commander: An Unpopular Regime's Muscle

Mohammad Pakpour is the commander of the IRGC’s Ground Force; former IRGC top commander Mohammad Ali Jafari promoted him to the post in 2009. The 2015 nuclear deal, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), lifted U.S. sanctions against him. However, the Trump administration designated Pakpour in 2019 under counterterrorism authority Executive Order (E.O.) 13224, noting that the Ground Force deployed to Syria to support the Quds Force under his command—a mission that Pakpour publicly admitted to in 2017. The U.S., however, has not sanctioned Pakpour under human rights authorities, even though he commanded the Ground Force when it indiscriminately gunned down hundreds of peaceful protesters in November 2019. The E.U., on the other hand, sanctioned Pakpour as a human rights violator in 2021, citing his command role during that slaughter. Before heading the IRGC’s Ground Force, Pakpour served as the deputy for coordination of the IRGC’s Ground Force, commander of the IRGC’s 8th Najaf Division, and commander of the IRGC’s 31st Ashoura Division.

Historical Background: "The Mosaic Doctrine"

Four years after the 2003 U.S.-led invasion and occupation of Iraq, Mohammad Jafari took the helm of the IRGC. He implemented a plan, the “Mosaic Doctrine,” that originated as a response to the U.S.’s lightning-speed toppling of Saddam Hussein. The “Mosaic Doctrine,” assumed that if Iran was invaded next, the invading forces would have technology and conventional capabilities that far surpassed Iran’s. The “Mosaic Doctrine” is an asymmetric warfare concept that envisages a protracted and dispersed insurgency to compensate for Iran’s weaknesses. To that end, in 2007, the year in which the Basij was brought under the command of the IRGC, the Ground Force was divided into 31 provincial units plus one for Tehran, in addition to its operational combat units that include infantry, artillery, engineering, airborne, and special operations. The decentralization was intended to improve unit cohesion at the local level and command and control in the event of a devastating air campaign against operational centers and to enable the Ground Force to rapidly deploy to hotspots in urban areas in times of unrest.

The Ground Force's Functions: A Foreign Fighting Force

Like the Basij, the IRGC’s Ground Force preserves internal security, protects the nation from foreign invasion, and participates in military operations abroad. The Ground Force, with its 100,000 to 150,000 active personnel, split between provincial and operational units, can implement larger operations at home than the LEF and Basij and larger operations abroad than the Quds Force.

The Ground Force’s internal security focus involves protest suppression through the use of excessive force. It has deployed tanks, armored vehicles, and military-grade weaponry against protesters. It also conducts counterinsurgency campaigns against Kurdish militant separatists in northwest Iran and Baluchi separatists in the southeast. The Ground Force’s special operations unit, known as the Saberin, often takes the lead on such operations, and has been deployed in discrete areas against protestors in the aftermath of the death of Mahsa Amini.

The Saberin’s skills blend well into the irregular warfare approach to national defense called for in the “Mosaic Doctrine.” It specializes in airborne operations, which could assist attacks on the enemy’s rear area supply-lines and communications. This unit is also skilled in explosives, a low-cost and effective means of targeting enemy convoys with roadside bombings, and demolition, which enables it to destroy roads and bridges needed by the enemy for supplying its troops. Furthermore, the Saberin is trained in mountain warfare, an advantage in Iran’s mountainous terrain.

The Ground Force appeared to deviate from its fighting doctrine in deploying to Syria to rejuvenate a faltering ground campaign against anti-Assad rebels. Its forces fought alongside the Artesh, the Basij, the Quds Force, its proxies, and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s army and pro-Assad militias in key operations such as “Dawn of Victory,” which led to the fall of Aleppo in 2016. The Syrian Civil War, therefore, motivated the IRGC’s Ground Force to adopt expeditionary and conventional power projection roles. Some Ground Force soldiers remain in the country at permanent bases run by the IRGC.

The Navy Force

The IRGC’s Navy Force, under the leadership of Rear Admiral Alireza Tangsiri, is a threat to international maritime security. First, this section highlights Tangsiri’s aggressive disposition, which has endeared him to the supreme leader. Then, it identifies the role that this branch would likely play in the event of military escalation. Finally, it points out some of the operations the IRGC’s Navy Force conducts to intimidate and retaliate against its enemies and deter military action against Iran.

The Navy Force's Commander: Khamenei's Favorite

The Navy Force Commander Rear Admiral Alireza Tangsiri was appointed to lead the branch of approximately 20,000 active personnel in 2018. He is known to be one of Supreme Leader Khamenei’s favorite commanders, which is not surprising given his antipathy toward the U.S. He sometimes boasts that Iran is willing and able to retaliate at sea for what he perceives as acts of aggression against his country. The U.S. Department of the Treasury designated Tangsiri under E.O. 13224 in 2019, noting his threats to block the Strait of Hormuz—a strategic channel through which 30 percent of total global oil consumption flows. He directs the branch’s sabotage of commercial vessels in international waters and occasionally echoes Khamenei in asserting ownership over the Persian Gulf. He disdains world order, once saying that the “law of the world is the law of the jungle,” an implicit affront directed toward U.S. global leadership. Before becoming commander of the IRGC’s Navy, Tangsiri served as Navy deputy commander and commander of the IRGC’s 1st Naval District.

The Navy Force's Function: A Threat to Maritime Security

The IRGC’s Navy has developed anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities, including the use of airborne, coastal, undersea, and surface warfare assets, to prevent enemy vessels from operating in the strategic Persian Gulf. In 2019, the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency’s report on Iran’s military power listed some of these assets. The IRGC’s Navy has contact and influence mines; an arsenal of drones, or unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs); unmanned sea vessels (USVs), including unmanned submarines; fast attack crafts (FACs) and fast inshore attack crafts (FIACs); and shore-launched anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), anti-ship ballistic missiles, and anti-radiation missiles. It operates out of several bases, including Bandar-e Abbas on the Strait of Hormuz.

In the event of military escalation, the IRGC’s Navy could conduct asymmetric attacks against a superior navy, for example, using FACs equipped with machine guns, unguided rockets, torpedoes, and ASCMs. Many of these speedy vessels, seeking to avoid direct or sustained confrontations, could ambush and overwhelm large enemy vessels, the mainstay of an advanced navy. Moreover, since large vessels cannot maneuver well in the Strait of Hormuz, a 30-mile-wide chokepoint, Iran could deploy its A2/AD capabilities to try to shut down the Strait of Hormuz, but doing so could inflict major costs on its own oil-dependent economy. Iran could also target its adversaries’ naval assets, such as ports, oil installations, and desalination facilities. Tehran’s asymmetrical capabilities at sea, and its potential to obstruct key shipping lanes, add to its naval deterrent.

Tehran continues to signal that it remains a threat to maritime security by conducting attacks against commercial vessels in international waters as well as harassing the U.S. Navy. The IRGC’s Navy has seized foreign vessels that it claims are freighting smuggled oil, often as part of an effort to retaliate and seek leverage against governments worldwide. In 2021, for example, the IRGC’s Navy boarded and took control of a South Korean vessel as tensions flared over frozen Iranian assets held in South Korean banks. In May 2022, it seized two Greek vessels in the Persian Gulf a month after Athens impounded an Iran-flagged, Russian-operated tanker in the Aegean Sea that the U.S. had designated for its ties to a Russian bank. Greece later handed over the vessel to the U.S., which confiscated the Iranian oil onboard.

The IRGC has since at least 2016 patrolled the waters near the Bab al-Mandeb Strait, supporting and enabling the Houthis with intelligence to conduct attacks on international shipping. The first vessel that was tasked with this responsibility, the Saviz, was attacked with a limpet mine in 2021, which caused damage to the vessel and forced it to return to Iran. Tehran replaced the Saviz with another cargo vessel, likely equipped with ship-tracking and other intelligence capabilities, that has been present in the waters near the Bab al-Mandeb Strait throughout the Houthis’ assault on international shipping and is providing the Houthis with data they need to accurately target ships with missiles and drones.

The Aerospace Force

This section opens with an account of the Aerospace Force commander’s ascent through the ranks of the IRGC. The remainder is organized around the Aerospace Force’s core capabilities—missiles, air defense systems, and drones. These capabilities are discussed in terms of establishing deterrence against Iran’s enemies and setting up the option for an unprovoked strike.

Amir Ali Hajizadeh: The Next Soleimani?

Since 2009, Amir Ali Hajizadeh has commanded the IRGC’s Aerospace Force. He began his military career in the Iran-Iraq War as a “special unit” sniper, but he was closely associated with an artillery division. With the backing of Hassan Tehrani Moghaddam, the renowned “godfather” of Iran’s missile program, Hajizadeh ascended the ranks of the IRGC, and soon became commander of a missile unit in that war. In 2003, he was elevated to command Iran’s air defense systems.

IRGC's Aerospace Commander Amir Hajizadeh

In the years since becoming the Aerospace Force commander, Israeli security officials have begun to question whether Hajizadeh is taking on the role formerly played by the revered late Quds Force commander Qassem Soleimani. Hajizadeh is responsible for drone strikes against Israeli-linked vessels in international waters—attacks which the former Quds Force general may have likely assigned to proxies. His close relationship with the supreme leader, indicated by his longevity at the helm of the Aerospace Force, has increased his stature at home.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury designated Hajizadeh in 2019, explaining in a press release his role in overseeing Tehran’s missile program and his responsibility for the shooting down of civilian airliner MH17 on July 17, 2014 with a surface-to-air missile, which caused the death of 300 people. Three years later, the E.U. designated Hajizadeh, citing his role in UAV-related defense cooperation, including the supply of Iranian-made drones to Russia. Iran’s drones are not only a threat to regional security, but therefore also a threat to European security.

Iran’s ballistic missile arsenal—the largest and most diverse in the region—poses a major challenge to regional security as well, especially as the regime improves the range, accuracy, and lethality of these munitions. Hajizadeh once said, "the reason we designed our missiles with a range of 2,000 km is to be able to hit our enemy the Zionist regime from a safe distance.”

The Aerospace Force's Function: Deterrence?

Hajizadeh’s appointment to lead the Aerospace Force coincided with an expansion of the branch’s scope to include Iran’s missile and space programs, the latter which is dedicated, in part, to testing missile systems and technologies. Iran is seeking to improve the accuracy of its ballistic missiles to enhance the credibility of a long-range strike against targets in Israel from secure positions inside Iran. This capability would compensate for the weakness of its air force, which has degraded over time because Iran cannot import the materials it needs for its planes.

Iran’s missiles have already proven accurate enough to strike U.S. targets in the region. For example, in January 2020, Iran hit an Iraqi military base housing U.S. troops in retaliation for the assassination of Qassem Soleimani. The Aerospace Force’s ballistic missile arsenal expands Iran’s options for retaliation or an unprovoked strike against targets in the region.

Iran has also claimed ballistic missile attacks on the Kurdistan region of Iraq in March 2022 and January 2024; in both, it claimed to be targeting Israeli spy posts when in fact it hit civilian housing belonging to wealthy Kurdish businessmen. Iran also fired ballistic missiles at alleged ISIS targets in Iraq and Syria in January 2024, claiming retaliation for a deadly ISIS bombing in Kerman, Iran on the anniversary of Soleimani’s assassination by the U.S. Additionally, Iran struck Baluchi groups in Pakistan in January 2024, to which Pakistan responded with its own strikes in Iran against separatist groups.

Operational control of Iran’s ballistic missile arsenal is delegated to the Aerospace Force’s Al-Ghadir Missile Command, first designated by the U.S. Department of the Treasury in June 2010 under E.O. 13382, which is intended to block the property of persons and their support networks engaged in the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD). This element within the IRGC Aerospace Force has been involved in medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) test launches since at least 2008.

Al-Ghadir Missile Command works with Iranian entities that develop and produce ballistic missiles, such as Shahid Bagheri Industrial Group (SBIG), which produces Iran’s solid-propellant ballistic missiles. It has participated in SBIG’s Fateh-110 short-range ballistic missile and its Ashura medium-range ballistic missile projects. The Al-Ghadir Missile Command is currently under the direction of Mahmud Bagheri Kazemabad, whom the U.S. Department of State identified as a WMD proliferator in March 2022. Most of Iran’s missiles are known to be nuclear-capable. If Iran produces a nuclear-armed ballistic missile, its deployment and management would likely fall to this element in the Aerospace Force.

Iran’s air defense systems have been strategically deployed in Iran to increase the potential costs of aerial incursions or strikes on its homeland. In 2019, Iran fired surface-to-air missiles and struck a $100 million U.S. Navy RQ-4A Global Hawk reconnaissance drone allegedly infringing on Iran’s airspace. The U.S. claimed the drone was flying over the Strait of Hormuz, an international waterway.

Iran’s air defense systems also protect nuclear installations, which Iran already goes to great lengths to shield by building underground and deep within mountainsides. These systems also protect missile silos, which are sometimes called “missile cities” due to their proximity to population centers. In recent years, the Aerospace Force has displayed advanced air defense capabilities. In October 2021, for example, in the Velayat Sky 1400 air defense drill, Iran showcased several surface-to-air missile systems, along with upgraded radar, surveillance, communications, and electronic warfare systems.

Iran’s UAVs serve a function similar to its missiles; allowing Iran to strike distant targets in the region. Iran launched the Shahed-136 drone—the same type being shipped to Russia—at the Israeli-linked oil tanker Mercer Street in the Gulf of Oman in 2021, killing two Europeans and denying that it played a part. This attack is what led one analyst to surmise that “the balance of power” within the IRGC had shifted toward the Aerospace Force’s preference for overt retaliatory strikes, as opposed to proxy wars. Again, in a separate incident in November 2022, a U.S. Navy forensic investigation revealed that the Shahed-136 was used to attack an Israeli-linked tanker. Some analysts believe the attack may have been retaliation for an Israeli strike on a convoy at the Iraq-Syria border a week prior. If viewed as retaliation, these attacks might be understood as an effort to deter Israel from future strikes. However, Iran’s true intentions are seldom clear; its attacks could also be intended to seek leverage or for intimidation.

The Intelligence Organization

This section begins by pointing out the recent leadership transition in the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization. Then, it mentions the impetus behind Supreme Leader Khamenei’s decision to rename and expand the scope of the IRGC’s Intelligence Branch in 2009. Finally, it indicates the entity’s roles at home and abroad.

The IRGC’s Intelligence Organization is led by Mohammad Kazemi, who replaced Hossein Taeb in June 2022 after a series of intelligence failures, including the high-profile assassination of Quds Force Unit 840’s deputy commander Hassan Sayyad Khodaei that Iran blamed on Israel. Kazemi was previously the head of the IRGC’s Intelligence Protection Organization, which is responsible for counterintelligence and is separate from the Intelligence Organization. In June 2009, shortly after the reelection of Ahmadinejad, Supreme Leader Khamenei established the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization, expanding the scope of the former IRGC Intelligence Branch, and putting it in charge of suppressing the rapidly growing “Green Movement.” The new intelligence and security organization, brought under the leadership of Taeb after he was removed from his post as the head of the Basij, incorporated seven separate divisions, including Khamenei’s personal intelligence body known as Department 101, a Basij volunteer unit, a cybersecurity unit, and a directorate in the Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS). Domestically, the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization pursues, arrests, interrogates, and tortures dissidents, even running its own section at the notorious Evin Prison. Abroad, it provides material, logistical, technical, and operational support to the Quds Force, which takes the lead on external military operations. The IRGC’s Intelligence Organization also conducts counterintelligence operations, the primary goal of which is to protect IRGC personnel, operations, and facilities from infiltration, espionage, and information leaks.

Quds Force

The Quds Force is the IRGC wing responsible for external operations. Thus, this section focuses on foreign activities, although it should be noted that the Quds Force’s training and skills would lend well to the “Mosaic Doctrine” and its focus on unconventional tactics. The first part describes Esmail Qaani, the current Quds Force commander, in comparison with the former Quds Force commander, Qassem Soleimani. The second part discusses the IRGC’s operations abroad; and its focus on proxy warfare, the primary way in which Tehran advances its foreign policy objectives in the region. The third part touches upon Quds Force operations in the strategic countries of Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen.

The Quds Force Commander: Soleimani's Successor

Esmail Ghaani commands the Quds Force, the expeditionary wing of the IRGC made up of between 5,000 and 10,000 special operations personnel. Its operatives typically keep a low profile to afford Tehran plausible deniability when operations fail or have the potential to escalate hostilities. Ghaani ascended to this position in January 2020 after a U.S. Reaper drone struck and killed then-commander Qassem Soleimani at Baghdad International Airport while he was allegedly plotting to kill Americans. Upon assuming this post, Ghaani became the commander not only of the Quds Force but of the proxy forces stood up by Soleimani.

IRGC's Quds Force Commander Esmail Qaani

Qaani lacks several of the characteristics that made Soleimani effective in the Levant. First, he does not have the same experience in the Arab world, as he was earlier in his career a member of the Quds Force’s Ansar Corps, which operates in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia. Soleimani had longstanding relationships with militia leaders in Iraq, some of whom had roots in Tehran’s support for rebels fighting against Saddam Hussein dating back to the Iran-Iraq War. Qaani also does not speak Arabic, the language used by militia leaders, as well as Soleimani did. Moreover, Qaani, Soleimani’s longtime deputy commander, is known to be more bureaucratic than his former boss, whose charisma made him a symbol of “resistance” against Western powers and Israel.

Still, the Quds Force is a global enterprise with directorates and cells in every region of the world. The U.S. government and its allies have uncovered and disrupted plots in Africa, Germany, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Kenya, Bahrain, and Turkey. But the Quds Force, sometimes working in coordination with terrorist groups such as Hezbollah, criminal organizations, or drug cartels to mask its activities, has been implicated in many other violent activities worldwide. Soleimani’s death was a major blow to the effectiveness of the IRGC’s proxy operations in the Levant. However, the Quds Force will continue to pose a grave threat to international peace and security for the foreseeable future.

Qaani may have exceeded expectations in terms of his ability to unite the Axis of Resistance in a quasi-military alliance that resembles NATO Article 5. An attack on one is supposed to trigger the intervention of all other Iran-backed militias in the network. Like his predecessor, Qaani has coordinated among various factions across the Middle East, each of which has their own domestic circumstances and pressures. Qaani’s contributions, though, have deepened the Axis of Resistance’s integration. This has been shown in that other members have joined in war against Israel, ostensibly in defense of Hamas, which the Israeli military and political establishment vowed to destroy. This is the case with Hezbollah, launching daily missiles and drones across the border into Israel, and also the Houthis, who claim to be attacking international shipping to harm Israel.

Iran and the militias it stood up are not only aligned in terms of strategic vision, but also coordinate at an operational and even tactical level of warfare, where Qaani as Tehran’s emissary has authorized and directed anti-Western and anti-Semitic attacks worldwide, including the October 7 Hamas terrorist attacks via a series of meetings in Beirut that hosted Qaani, along with Hezbollah and Hamas officials in the months leading up to the assault.

Unconventional Warfare Operations

Using subversion, kidnapping, assassination, bombings, sabotage, and proxy wars, the Quds Force continues to target dissidents and journalists in foreign countries; Jewish, Israeli, American, and Western targets; and regional adversary governments, particularly those bordering the Persian Gulf. Tehran’s subversion of foreign adversary governments typically relies on terrorist organizations. This is the case in Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, for instance, where Tehran sponsors violent groups that oppose the ruling monarchies. These groups are known to carry out attacks on civilians and government officials alike, often using weapons and training provided by the Quds Force.

Kidnapping and assassination plots against Western targets are often thought to be the responsibility of Quds Force Unit 840, though personnel from the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization also assist in these operations. On several occasions, kidnapping plots have targeted American journalists but were uncovered and disrupted by U.S. law enforcement agencies. In August 2022, for instance, a man armed with an AK-47 showed up at the home of an outspoken Iranian-American activist and journalist named Masih Alinejad, allegedly to abduct or kill her. More recently, the IRGC has targeted London-based journalists working at Iran International and BBC Persia for their coverage of the Mahsa Amini protest movement. The Islamic Republic has no qualms about killing activists or journalists who expose its malign domestic and foreign activities.

In April 2022, a Quds Force operative from Unit 840, held at an unspecified location in Europe, admitted to plotting attacks against an Israeli national working at the Israeli consulate in Istanbul, an American general in Germany, and a French journalist. He claimed he was offered $150,000 for organizing the assassinations and $1 million if they were carried out successfully. A month later, Colonel Hassan Sayyad Khodaei—believed to be Unit 840’s deputy commander tasked with planning antisemitic attacks around the world—was assassinated in Tehran. Shortly after his assassination, the Mossad foiled three Iranian plots to use terrorist cells in Turkey to attack Israeli citizens there, possibly in retaliation for the assassination of Khodaei.

More recently, the U.S. Justice Department revealed that the Quds Force had tried to kill former National Security Advisor John Bolton in a murder-for-hire scheme, an act of war interpreted as retaliation for the Soleimani assassination. In early June 2023, the U.S. Department of the Treasury designated Mohammad Reza Ansari, a member of a Quds Force external operations unit, as an accomplice in the assassination plot. Ansari’s involvement in intelligence gathering, as well as planning and executing of lethal operations against Iranian dissidents and non-Iranian nationals in the U.S., the Middle East, Europe, and Africa, was also highlighted. Furthermore, the U.S. Treasury designated Hossein Hafez Amini, an IRGC affiliate in Turkey, for providing material assistance to Quds Force operations in Turkey through his connections in the airline industry.

In December 2023, Quds Force Unit 400 was recruiting Afghans and working with al-Qaeda to target Israelis. Israel’s intelligence services have also uncovered plots targeting Jewish people in Turkey, where the government of Israel warned its citizens not to travel because of active plots backed by Iran in June 2022. Kenya foiled a terrorist plot against Israeli interests in 2021 and in 2012 discovered 33 pounds of RDX explosives, stored by Iranians who were deemed by Kenya to be Quds Force operatives. A report from the time added that Kenya suspected the highest levels of the regime approving of an operation to target public gatherings, Kenyan officials, and foreign establishments.

The U.S. and Israel discovered an operation in Ethiopia to surveil and gather intelligence on the Israeli and Emirati embassies, though public reports did not clarify which intelligence branch was responsible, whether the Quds Force, the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization, or the Ministry of Intelligence, or some combination. There have also been thwarted Iran-backed attacks in Georgia, Thailand, and India.

Proxy war, however, is Iran’s favored means of achieving its foreign policy interests. Its proxy network, sometimes referred to as the Iranian Threat Network (ITN) or Axis of Resistance, comprises between 80,000 and 200,000 radicalized individuals, many who adhere to the Shia sect of Islam and are dispersed throughout the strategic countries of Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen. The main groups in the Quds Force-led proxy network are Lebanese Hezbollah, Iraqi Shia militias, the Houthis in Yemen, the Fatemiyoun Brigade, the Zainabiyoun Brigade, and Palestinian terrorist groups Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ). These groups loyally conduct operations at the behest of Tehran, but some operate independently—even at times against Tehran’s interests. These trends have become exacerbated in the aftermath of Soleimani’s death and Qaani’s difficulty in managing the sprawling terror enterprise.

The Quds Force recruits from mosques, cultural centers, shrines, and universities. For example, the Quds Force is believed to recruit foreigners in Qom, one of the holiest Shia locations in Iran. Recruits are identified at religious seminaries and transferred to Quds Force training centers, such as the Manzariyah training center near Qom. Foreigners from Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, and Syria frequently travel to Iran on religious pilgrimages and sometimes find themselves motivated to join the Axis of Resistance.

Iran’s Al-Mustafa University also doubles as a recruitment site. In December 2020, the U.S. Department of the Treasury designated the university, which has branches in more than 50 countries, because Afghan and Pakistani students were recruited for intelligence purposes and for brigades deployed to Syria. The Quds Force’s ability to implement violence worldwide depends on effective outreach to grow the numbers of loyal, radicalized individuals. It also depends on the propaganda campaigns of its proxies, which the Quds Force manages and coordinates through its Iranian Islamic Radio and Television Union (IRTVU).

As with Basij recruits, however, Quds Force recruits are not all equally loyal to Tehran. Materialistic motives compete with ideological motives, the latter which can be more powerful in promoting subservience to Tehran’s interests. Therefore, the Quds Force’s training regimen relies heavily on inculcating recruits with the Islamic Republic’s unique brand of antisemitism, anti-Americanism, and anti-Westernism—concepts often cloaked in the rhetoric of anti-colonialism and anti-Muslim oppression.

Iran vows to support the muqawama (“resistance”) movement, opposed to what it perceives as imperial powers present primarily in the Middle East. However, the notion also aligns with anti-capitalist, anti-American leftist groups in the Western hemisphere. To intensify the commitment to “resistance” and thus grow the propensity for violence, the IRGC also perverts the commonly-held Shia belief in the eventual return of the Twelfth (“Hidden”) Imam from occultation, transforming it into an apocalyptic fantasy in which Imam Mahdi returns and leads an army of good to triumph over evil.

This framework convinces members of the IRGC and its proxy network that violence against the U.S. and Israel is justified as part of Mahdi’s crusade. The religious and ideological training regimen also incorporates velayat-e faqih, the Islamic Republic’s foundational doctrine, which contends that Iran's supreme leader is the preeminent Shia religious authority and should be emulated and followed by all Muslims worldwide.

These aspects of Iran’s radicalization campaign, focused on creating hatred against Iran’s adversaries, are part of Tehran’s long-standing policy of exporting the revolution. However, it should also be noted that the Quds Force extends its outreach and recruitment to Sunnis, such as the Palestinian terrorist groups, as well as Kurds. Tehran seeks legitimacy through pan-Islamism, calling for the unification of the ummah (“the Muslim community”). These pan-Islamic appeals broaden the pool of potential candidates for recruitment.

The Quds Force carries out military training as well. Basic weapons training typically lasts 20 to 45 days, but some recruits are introduced to more advanced weaponry, including explosives, mortars, and drones; logistics and support; and strategy. The Imam Ali training complex, west of Tehran, features a firing range for rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) and other weapons; and driver and combat training courses, which include simulations of cityscapes and mountainous terrain. Facilities in Esfahan provide demolition and sabotage training. The Quds Force also trains its trusted proxies to facilitate training courses. Lebanese Hezbollah has become an ideal recruiter, trainer, and commander, given its ability to communicate in Arabic, like most potential Iraqi, Syrian, Palestinian, and Yemeni recruits; its religious and ideological ties to the Islamic Republic; and its guerilla, UAV, cyber, and propaganda capabilities.

Furthermore, the Quds Force arms and equips its proxies and partners. Quds Force Unit 190 is believed to be tasked with weapons transfers, according to a Fox News report from 2017. To deceive foreign intelligence services, it has used front shipping companies to smuggle weapons and equipment, oil tanker convoys, and even heavily-guarded pilgrim convoys that cross into Syria ostensibly to visit religious shrines—some of which Iran built. Among the weapons it provides are UAVs; USVs; rockets; cruise, ballistic, and anti-tank guided missile systems; small arms ranging from machine guns to sniper rifles; land and limpet mines; improvised explosive devices (IEDs); explosively formed penetrators (EFPs); explosive materials; mortars and artillery systems; RPGs; claymores; man-portable air defense systems (MANPADs); and radars, night vision goggles, and armored personnel carriers.

In addition to Quds Force Unit 190, Israeli media reported in June 2023 on a separate unit responsible for weapons smuggling and logistical operations, known as Unit 700. The newly-identified unit, headed by Gal Farsat, who is known to have extensive connections to senior officials in Syria, Lebanon, and Iran, is believed to be responsible for transferring military equipment to Iran-aligned militias, particularly in Syria and Lebanon. These responsibilities appear to overlap and could conflict with those of Unit 190.

The Quds Force’s mission to build up its proxies and partners’ military capabilities is a low-cost way to project power, but Tehran takes a risk that these entities, once empowered, will pursue divergent interests. The following part of this section looks in more detail at how the Quds Force accomplishes its aims in major theaters of operation. It offers a historical account of the Quds Force operations in Iraq during the U.S. occupation and a description of the challenges facing the proxy leadership structure in Iraq. Then, it turns to Syria, with an account of the Quds Force’s role in the Syrian Civil War and a view of the assets, capabilities, and personnel under its management in Syria. Finally, it touches upon Quds Force activities in Lebanon and Yemen.

Iraq: Pulling Baghdad into Tehran's Sphere of Influence

While U.S. and coalition forces occupied Iraq in 2003, the Quds Force under Soleimani’s leadership was transferring weapons, including the IEDs frequently used as roadside bombs against the U.S. and even deadlier EFPs, to insurgent militias. In overseeing the transfer of these weapons, Soleimani was responsible for the deaths of an estimated 600 U.S. servicemen and women, a staggering 17 percent of all U.S. deaths in the war. Iraqi militias were also trained in Iran in guerrilla tactics, light arms, IEDs, marksmanship, and anti-aircraft missiles to bolster the insurgency against U.S. and coalition forces.

A powerful Iran-backed militia during the Iraq War, Muqtada al-Sadr’s Mahdi Army, was responsible not only for the death of many Americans but thousands of Iraqis in a bloody two-year sectarian civil war that began in 2006 after Shia militants retaliated against Sunni civilians for an al-Qaeda attack on the al-Askari shrine, considered to be one of the holiest Shia sites. Today, unlike most Iran-backed militias, the Mahdi Army, rebranded as the Peace Brigades, opposes Iranian meddling in the Iraqi political system and society.

The U.S. completed the withdrawal of most of its troops in 2011. Three years later, Mosul fell to ISIS, a Sunni extremist offshoot that emerged from the remnants of Abu al-Zarqawi’s al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI). After the U.S. withdrawal, ISIS eventually took control of one-third of the country. In response to this metastasizing terrorist group, then-Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki established the Popular Mobilization Forces in 2014. The PMF was dominated by Iran-backed militias, some of which were loyal to Iran’s supreme leader; others were loyal to Muqtada al-Sadr. Shia youth responding to Grand Ayatollah Sistani’s fatwa calling for young men to join the fight against ISIS also joined the ranks but retained their loyalty to Sistani.

Therefore, the PMF groups were united in their opposition to ISIS but not in their allegiances. Both the U.S. and the PMF fought against ISIS separately, and it was largely defeated in 2017, but the PMF remained divided regarding its loyalties to these three powerful Shia figures. Today, despite divergent loyalties, the PMF is a government-funded state institution, nominally under the command of the Iraqi prime minister. At the same time, the pro-Tehran militias in the PMF, such as the Badr Organization, Asaib Ahl al-Haq (AAH), and Kataib Hezbollah (KH), often act in Tehran’s foreign policy interests, undermining Iraqi independence and sovereignty.

These militias rank among the most powerful of Iran’s proxies. Their management remains the Quds Force’s responsibility. Supreme Leader Khamenei, Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS), and the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization each recognize the Quds Force’s primacy in Iraq. A Quds Force unified command structure, the Ramazan Corps, manages military, intelligence, terrorist, diplomatic, religious, ideological, propaganda, and economic operations in Iraq. Ghaani implements policy in Iraq and is probably more powerful than the current Iranian ambassador. With that said, it should be noted that diplomatic posts are often appointed to members of the IRGC, rather than the foreign ministry. A former ambassador to Iraq, Iraj Masjedi, was, prior to his ambassadorship, a Quds Force operative and confidant to Soleimani. Iran’s current ambassador to Iraq, Mohammad Kazem Al-e Sadeq, was also close with Soleimani. He served in several positions in the Iranian embassy in Baghdad, at one point a member of the board of directors of an association which honors IRGC martyrs, particularly those who have served in its Intelligence Organization.

Ghaani manages the Iraq file in a way similar to Soleimani, paying attention to the religious, political, and military dimensions of Tehran’s interests in Iraq. For example, he meets with Iraqi clergy in Najaf; influential politicians and PMF commanders in Baghdad; militia commanders in Samarra; and Kurdish leaders in Erbil. However, though he is in charge of Iraq's proxy and partner network, other senior Quds Force commanders have likely stepped into the void created by Soleimani’s death. This is not to mention that other Iranian entities like the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization and the Ministry of Intelligence are also playing a role in managing the Iraq file. Ghaani cannot command the many roles that Soleimani played, so a sort of committee may emerge atop the proxy leadership structure in Iraq.

The leadership vacuum in the proxy network in Iraq resulted not only from the death of Soleimani but also from the death of the PMF’s former de facto commander, the Persian-speaking KH commander Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, in the same January 2020 U.S. drone strike in Baghdad. Muhandis administered personnel, coordinated logistics, and set and implemented policy within the PMF. The absence of Muhandis and Soleimani—who together mediated between militia leaders inclined to compete for state resources, prestige, and rank in the PMF—inflamed divisions in the Iraqi proxy network. Competition between KH and AAH has occasionally devolved into internecine turf wars and assassinations. The Iraqi militias became less cohesive in the absence of these two individuals.

They also became more disobedient. The PMF militias have an interest in remaining on good terms with their benefactor Iran. However, they also face internal pressures to conduct attacks that may not be in Tehran’s interest. The regular attacks against Iraqi government assets and U.S. diplomatic and military personnel could be a response to demands from the groups’ radicalized elements. They could also have been directed by the IRGC. The Iraqi government remains a target of KH and AAH, despite Ghaani’s efforts to rein them in. Throughout the Biden Administration’s nuclear negotiations with Tehran, Iraqi proxies picked up the tempo of missile and drone strikes against the U.S. military—which remains in Iraq to advise, assist and train its partners in preventing the resurgence of terrorist groups. The increased frequency of attacks demonstrates a lack of deterrence, likely resulting from the Biden Administration’s reticence to use force in response.

Therefore, Iran’s interests may have shifted, but that does not mean the militia members will adjust their religious and ideological motivations. With the obedience of the militias in question, the Quds Force adopted a new approach. Beginning after the death of Soleimani and Muhandis, the Quds Force began to identify its most ardent loyalists from the larger groups and re-form them into smaller, elite units that report directly to the Quds Force. The recruits are often sent to Quds Force or Lebanese Hezbollah-run training camps and receive instruction in core capabilities, such as drone and information warfare. The newly-formed groups are sometimes mistakenly identified as KH front groups, but they are often in fact separate entities.

Despite its occasional disobedience, KH remains one of Iran’s most trusted Iraqi proxy groups. The Combatting Terrorism Center (CTC) at West Point reported in late 2021 that KH and groups linked to it coordinate logistics in Iraq with the support of the IRGC and Lebanese Hezbollah. PMF Brigade 17’s commander Hassan al-Sari, aka Saraya al-Jihad, is a key logistician for KH in southern Iraq. He oversaw missile systems deployed in Iraq’s Maysan governorate, near its southeast border with Iran, as of October 2020, along with then-Quds Force commander of operations in southern Iraq, Brigadier General Ahmad Forouzandeh. The Quds Force trusts KH to help manage the weaponry it deployed in Iraq.

The CTC reported that rockets and missiles are brought into Iraq in their constituent parts—body, engine, and warhead—and then reassembled, probably with the help of Quds Force engineers and technicians. By transporting them in parts, they are easier to conceal. The weapons deployed to Iraq—particularly missiles, rockets, and drones—severely undermine internal security and stability. Iraqi officials accused KH and AAH of ordering a drone strike on former Prime Minister Mustafa al-Khadimi’s residence, weeks after pro-Iranian groups were routed in national elections in late 2021, to demonstrate their willingness to resort to violence if political outcomes are unfavorable. The officials added that Tehran probably did not direct the attack, given that it wishes to avoid an escalation of hostilities between Shia groups in Iraq. However, it is seldom clear where orders originate, allowing Tehran to disavow any knowledge of them.

Pro-Tehran political figures—often from Shia militias—hold high-ranking posts in the government that they are willing to defend with violence. From these posts, the militias can advance Tehran’s security interests. On one such occasion, the Obama administration could not convince Iraq's prime minister to close down its air space to Iranian planes flying supplies to the Assad regime during the Syrian Civil War, as then-Minister of Transport Hadi al-Amiri came from the powerful Iran-backed Badr Organization.

Up to 70 percent of personnel in the Interior Ministry, which controls the Iraqi police force, reportedly owe their loyalty to Iran-backed militias. In 2014, the ministry came under the effective control of Badr Organization commander Hadi al-Amiri. Given the Interior Ministry’s personnel composition, the police force tends to permit the militias to operate freely in strategic areas of Iraq. This helps them secure the “land corridor” through Iraq for the transshipment of weapons and equipment to Syria and Lebanon. According to a U.S. Department of Defense report, Iraq’s police and emergency response division, both subunits of the Interior Ministry, as well as the Iraq Army’s Fifth and Eighth Divisions, “are the units thought to have the greatest Iranian influence.” However, the report notes, “officers sympathetic to Iranian or militia interests are scattered throughout the security services.”

Through the IRGC, Iran has built a network of proxies and partners in Iraq that are well-represented not only in Iraq’s security agencies, but also in the elected branch of Iraq’s government. While formally integrated within the Iraqi government’s chain of command, which is headed by the prime minister, the Iran-backed Iraqi militias operate independently of the Iraqi state. They often do the bidding of Tehran, thereby eroding the sovereignty of Iraq’s government. In other words, they operate outside the chain of command to conduct attacks against the U.S. military in Iraq.

There have been over 70 attacks against U.S.-operated facilities in Iraq, between Hamas’ October 7 terrorist attack against Israel and early February 2024. These attacks were launched without the approval or directive from Iraq’s government. The cues and directives for these attacks come from Tehran.

Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed al-Sudani has implored the militias to stop attacking, as he likely wants to avoid tit-for-tat escalation between the militias and the U.S. He said in mid-January 2024, ahead of planned bilateral negotiations between the U.S. and Iraq regarding the U.S. troop presence, that “halting all [militia] attacks…is our objective.” Then, he added that “we [also] call for stopping the coalition’s drone flights across Iraq.” Yet, the militias have continued to advance their rocket and drone campaign in Iraq, with the aim of evicting the U.S. military from the region and particularly Iraq. This goal is shared by the militias and Tehran.

Sudani is aligned with the Iran-backed militias, but he seeks to balance the interests of his hardline constituency, which advocates for more attacks on the U.S. and demands a complete U.S. troop withdrawal, with broad Iraqi foreign policy interests that include maintaining relations with the U.S. He has condemned the U.S. retaliatory strikes in Iraq, calling them a violation of Iraq’s sovereignty, and he has publicly stated that the U.S. military presence in Iraq is no longer necessary, while at the same time asking for strong relations with the U.S.

The U.S. is not the only foreign power that has received Sudani’s ire for military actions taken inside Iraqi territory. Iran has also conducted missile attacks inside Iraq. One such attack took place in January 2024, leading Iraq’s prime minister to recall the ambassador to Tehran. The Iranian regime conducted these attacks to relieve pressure from hardliners to take action against Israel and ISIS, because the regime had blamed Israel for being involved in the above-mentioned ISIS suicide bombing in Kerman, Iran.

Syria: Assets, Capabilities, and Personnel

Syria is another major theater that demonstrates how the Quds Force thrives in an environment of instability and weak central governance. Just as Tehran’s influence in Iraq rapidly grew out of the chaos it fueled and promoted after the fall of Saddam Hussein, the Arab Spring-inspired uprising against Assad provided a ripe opportunity for Iran to expand its presence in Syria. The Arab Spring hit Syria in 2011—the same year the U.S. withdrew most of its troops from Iraq.

The IRGC quickly came to the defense of its longstanding ally, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. At first, the Quds Force advised, assisted, and trained the Syrian army and pro-regime militias, but as the rebels gained the upper hand, the IRGC increased its presence in Syria. In 2015, Soleimani was dispatched to Russia to request its air support. Russia obliged, then began dropping barrel bombs—often on civilian populations—in support of Iran-backed proxy groups and Assad’s army. The IRGC provisioned its proxies with weapons and heavy-equipment and provided artillery support.

In 2016, the IRGC’s Ground Force, the Basij, and the Artesh, participated in operations that led to the fall of Aleppo, turning the tide of the war in Assad’s favor. Quds Force operatives then transformed Syria into a forward operating base to threaten Israel. In 2018, more than 2,000 Quds Force operatives and tens of thousands of proxy fighters remained in Syria. Their mission evolved from being covert and plausibly deniable to overt military entrenchment.

The Quds Force set up assets and capabilities in Syria that give Iran strategic depth, or the ability to fight a war closer to enemy territory. A study published by the Jusoor Center at the end of 2021 identified an IRGC presence at more than 180 sites in Syria, including military, security, and operational bases, and logistics hubs and outposts. The study shows a heavy concentration in the Damascus countryside, Aleppo, and the western banks of the Euphrates River in Deir Ezzor province.

The Quds Force oversees the IRGC’s construction of permanent basing, and then often runs the facilities. Among the most significant bases in Syria is the Imam Ali compound in Deir Ezzor province, near the strategic Al-Qaim-Abu Kamal border crossing with Iraq. On September 3, 2019, Western intelligence sources revealed that the compound, then under construction, would soon become operational. Six days after this report, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) struck the base, reportedly causing severe damage, and again in March 2020 strikes were carried out against the base. A human rights organization on the ground claimed that the U.S.-coalition conducted the latter strikes, but the U.S. denied the allegation.

An October 2022 Alma Center report notes that the base remains “very significant in bringing weapons [including ballistic missiles] into Syria.” The Imam Ali compound is the largest IRGC base in Syria, with the capacity to house thousands of personnel and store missiles underground. After the IDF struck the base in 2019, the IRGC reportedly began expanding the base’s underground storage facilities. The base is equipped with missile launch platforms and air defense systems.

Also strategically positioned in Deir Ezzor, the Al-Kum (“T-2”) base was assessed to hold high-value to the IRGC as recently as February 2022. The Tiyas (“T-4”) airbase—positioned 60 km west of the historic desert city of Palmyra, where another key IRGC compound is located—serves as a drone operations center. It was equipped with a Khordad air defense system in 2018, the same year in which the Israeli Air Force bombed the facility on two separate occasions. The Imam Ali compound, the T-2, and the T-4 bases are positioned along a straight line running through Syria from the border with Iraq to Homs. The network also crosses through Palmyra.

Iran’s forward deployment of air defense systems is the responsibility of the Quds Force and the Aerospace Force working together. Soleimani reportedly led efforts to coordinate their shipment, but the Aerospace Force’s deputy coordinator, Brigadier General Fereydoun Mohammadi Saghaei, took the lead on deploying them and possibly managing them, with the assistance of Lebanese Hezbollah. Israel insists that Iran withdraw these systems, along with its long-range missiles, as they impede its freedom of action and pose a threat to Israel’s homeland.

The Quds Force’s central command headquarters in Syria, known as Beit al Zajaja (“the Glass House”), was operational as of 2020, despite being struck by the IDF in late 2019. Located near the Damascus International Airport, militia commanders and government officials are believed to convene at the Glass House to plan, coordinate, and conduct military operations across the country. Additionally, field communications are received, and intelligence is aggregated here. There are also departments dedicated to military intelligence, counterintelligence, logistics, propaganda, communications, and operational command and control. Israel has struck Damascus International Airport on multiple occasions since 2019 to prevent its use as a transshipment hub, though public damage assessments have not indicated the command headquarters’ condition. On January 3, 2023, Israel fired missiles at the international airport, putting it out of service and causing material damage in nearby areas.

In addition to permanent basing, the Quds Force operates a network of research and manufacturing facilities in Syria. The Quds Force and Lebanese Hezbollah continue to implement Qassem Soleimani’s plan, dubbed the “Precision Project,” to assert control over the weapons facilities in Syria’s Scientific Studies and Research Center (CER). Iranian mechanical engineers in the past led efforts to develop Scud missiles with North Korea in a project known as “Project 99” at CER’s Institute 4000, located in Masyaf, Syria. Critical operations were moved there during the civil war.

The IRGC was tasked with rebuilding Institute 4000 after Israel bombed it in August 2022. A month later, Israeli Defense Minister Benny Gantz revealed the location of ten production facilities used for “mid- and long-range, precision missiles and weapons,” four of which were located outside the city of Masyaf, near the Lebanon-Syria border in northern Lebanon. These sites intend to secure the transfer of advanced weaponry. They enable engineers to reassemble missile, rocket, and drone components shipped from Iran, and upgrade existing arsenals with precision technologies. Quds Force Unit 340 oversees tech transfers, its proxies’ missile development, and the export of production capabilities.

The Quds Force, furthermore, operates a complex network of hubs and warehouses woven throughout Syria that allow it to ship weapons westward, toward the Israeli front. This logistics network, known as the “land corridor,” was a core interest motivating Iran’s intervention in the Syrian Civil War. The network has been used to move weapons to Assad, IRGC bases, and Lebanese Hezbollah, further enhancing the credibility of a threat to Israel’s homeland.

The IRGC coordinates logistics in Syria via an operations center, known as Unit 2250, located in Damascus, with satellite offices throughout the country. The Quds Force’s extensive involvement in logistics was revealed by the targets struck in a massive IDF missile and aerial campaign launched in 2018, after Israel’s air defense batteries intercepted 122-mm Grad rockets and 333-mm Fajr-5 rockets launched by the Quds Force at Israeli assets in the Golan Heights. In response to this unprecedented Quds Force rocket attack, the IDF hit 50 Quds Force targets, including a logistics complex in the Damascus countryside, and a weapons storage facility at Damascus International Airport.

The Iraqi Heyadrioun Division, stood up in 2015, supports Quds Force logistics operations in Syria. This division was trained to specialize in moving personnel and military cargo across borders en route westward from Iran and through depots at major Syrian airports; it is also responsible for escorting officials in Syria. Additionally, the Fatemiyoun and Zainabiyoun, largely made up of Afghanis and Pakistanis respectively, facilitate cross-border weapons transfers from the “Afghani security square,” near Albu Kamal’s city center in Deir Ezzor.

Senior Quds Force operatives embed in these units in a command role. They aim to create a cohesive proxy army out of an amalgam of languages, cultures, ethnicities, religions, and nationalities. Like its ballistic missiles, its proxy network in Syria allows Tehran to more credibly target Israel’s homeland in lieu of a modern air force. The proxies add to the asymmetric deterrent Iran seeks to establish through the use of terrorist organizations in Lebanon and Gaza.