Afghanistan

Support for Afghan Proxies

Iranian influence in Afghanistan has deep-seated roots reaching back to the 15th century when the Afghan city of Herat was the capital of the Persian Empire. Iran also shares ties with various groups in Afghanistan, particularly the Persian-speaking Tajiks and the Shi’a Hazara. During the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan (1979-1989), Iran supported Shi’a resistance efforts and opened its borders to Afghan refugees. After the Soviet Union withdrew, the first Gulf War occurred in 1990. A U.S.-led international coalition mobilized to repel Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait. As a result, Iraq, the major proximate threat to Iran since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, was effectively neutralized. Throughout the early to mid-nineties Afghanistan went through a civil war, which eventually led the extremist Sunni jihadist movement, the Taliban, to rise to power with the backing of Iranian geopolitical rivals Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. Afghanistan supplanted Iraq as the main threat facing Iran.

During the Afghan Civil War, Iran cultivated military and political influence in Afghanistan by backing elements hostile to the Taliban with ethnic, sectarian, and linguistic affinities toward Iran, namely the Hazaras in the West of the country and Tajiks in the North who formed the core of the United Islamic Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan, more commonly referred to as the “Northern Alliance.” By 1998, Iran had amassed 70,000 IRGC troops along its border with Afghanistan to defend against spillover from the conflict next door.

In August 1998, tensions between Iran and the Taliban reached a boil after the Taliban captured the city of Mazar-i-Sharif, a cosmopolitan and diverse city with a large Shi’a Hazara population. The Taliban brutalized the town’s Hazaras, raping and massacring hundreds. Amidst the chaos, Taliban soldiers besieged an Iranian consulate and executed nine Iranian diplomats and an Iranian journalist. As demands for retaliation grew, Iran stationed an additional 200,000 conventional forces along the border.

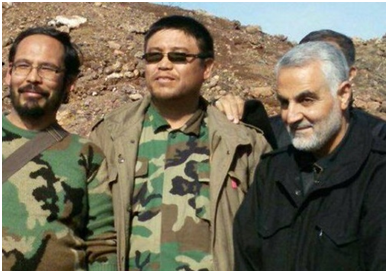

Since the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War, Iran has sought to avoid confrontation and heavy casualties, and so it refrained from direct intervention and opted instead to escalate its strategy of proxy warfare. Iran ramped up its support for the Northern Alliance, with former IRGC-Quds Force Commander Qassem Soleimani reportedly taking an active role in directing the Northern Alliance’s operations from Tajikistan, where the group had established bases from which to launch attacks into Afghanistan and coordinate efforts to resupply its fighters.

After the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) discovered that the Taliban was providing Al Qaeda safe haven in its territory, it authorized covert assistance to the Northern Alliance in 1999 to facilitate operations against the growing Al Qaeda threat. This marked a rare instance of the U.S. and Iran independently backing a guerilla movement, albeit for different ends. Following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks by Al Qaeda, America initiated hostilities against the Taliban government, a welcome development for Iran at the time.

While wary of the expanding U.S. military footprint in its environs, Tehran was willing to leverage American military might to neutralize its most pressing adversary. The U.S. and Iran held several rounds of secret shuttle diplomacy, leading to covert cooperation that went as far as Iran sharing intelligence detailing Taliban positions for the U.S. to strike. While many in Iran were skeptical about the efficacy of partnering with the U.S., Soleimani saw the situation as a win-win for Iran. He posited that even if the U.S. ended up betraying Iran after toppling the Taliban, their enemy would be defeated, and America would end up entangled in Afghanistan, similar to the Soviet Union. “Americans do not know the region, Americans do not know Afghanistan, Americans do not know Iran,” warned Soleimani.

Relations between the U.S. and Iran would ultimately sour following President George W. Bush’s 2002 State of the Union, in which Iran, Iraq, and North Korea were labeled the “axis of evil,” and the subsequent March 2003 invasion of Iraq. Iran’s threat perception changed as the U.S. was no longer the distant “Great Satan,” but a proximate threat with an expanding military footprint in the region that had toppled two neighboring governments and was ultimately bent on Iranian regime change.

As such, Iran’s primary objectives in Afghanistan shifted toward ensuring that the country remained sufficiently weak in order to preclude a further military threat toward it, and toward imposing costs on the U.S. to compel its withdrawal. Iran’s long-term interest is in a stable, friendly, and weak Afghanistan in order to prevent drug trafficking, terrorism, and refugee flows from spilling over into Iran. To that end, Iran pursued foreign direct investment in Afghanistan’s reconstruction and assistance in the fields of infrastructure, agriculture, energy, and communications.

At the same time, however, Iran played what former U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates termed a “double game” in Afghanistan, seeking good relations with the central government while also modestly funneling arms to insurgents of various ethnic and ideological stripes through the IRGC-Quds Force, according to U.S. intelligence. The haphazard way Iran has sought to play all sides off each other in pursuit of its short-term interests imperils its longer-term interest in a stable, friendly Afghanistan. It has also engendered enmity among broad swathes of the population, as evidenced by pushback and demonstrations against Iranian meddling in recent years.

Economic and Cultural Influence

Tehran has dramatically expanded its economic ties with Afghanistan in recent years to buy influence in the country. According to the Afghanistan Chamber of Commerce, Iran surpassed Pakistan as Afghanistan’s largest trading partner from March 2017-2018—with Iran exporting goods worth $1.98 billion. While foreign investment supports Afghanistan’s development, Iranian investment sought to undermine NATO and the Afghan regime’s efforts to stabilize the country. In 2010, Afghan President Hamid Karzai admitted that Iran was paying his government $2 million annually, but U.S. officials believe that this was just the “tip of the iceberg” in a multitude of Iranian cash inflows to Afghan groups and officials.

Iran’s economic influence in Afghanistan is best illustrated by its development of the western city of Herat, where Iran has developed the electrical grid, invested heavily in the mining industry, and invested over $150 million to build a school, mosque, residential apartments, a seven-mile road, and even stocked store shelves with Iranian goods. According to the head of Herat’s provincial council, Nazir Ahmad Haidar, “Iran has influence in every sphere: economic, social, political and daily life. When someone gives so much money, people fall into their way of thinking. It’s not just a matter of being neighborly.”

Furthermore, Iranian influence in Afghanistan extends past its economy and into Afghan culture and religion. Coordinated by an official under the office of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, Iran has funded the development of Shi’a organizations, schools, and media outlets in order to expand Iranian influence in Afghanistan. Mohammad Omar Daudzai, Afghanistan’s former Ambassador to Iran, has stated that “thousands of Afghan religious leaders are on the Iranian payroll.”

Recently, Iran has bridged its regional influence by creating the IRGC-backed Fatemiyoun Division, a group of Afghan Shi’a fighting in support of the al-Assad regime of Syria. Often recruiting Afghan Shi’a refugees in Iran, and to a lesser extent, Shi’as within Afghanistan itself, the IRGC offers a $500/month stipend and Iranian residency in return for joining pro-Assad militias. The Fatemiyoun was upgraded from a brigade to a division in 2015, indicating the militia’s ranks had grown to at least 10,000 fighters, with some estimates reaching as high as 20,000. The Fatemiyoun militants in Syria have typically been dispatched to dangerous fighting on the front lines with inadequate training and tactical preparation, leading to high casualty rates. Fatemiyoun survivors and deserters have described heavy-handed recruitment methods, including threats of being expelled from Iran and handed over to the Taliban in order to coerce marginalized Afghan refugees to fight in a war they have little understanding of or connection to. Human Rights Watch has identified at least 14 minors who fought and died in Syria for the Fatemiyoun Division.

Support for the Taliban

Demonstrating the lengths Tehran was willing to go to repel U.S. influence after the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, one of the primary groups the IRGC-Quds Force began arming was its former mortal enemy, the Taliban. Beginning in 2006, the IRGC-Quds Force began “training the Taliban in Afghanistan on small unit tactics, small arms, explosives, and indirect fire weapons” in addition to providing armaments “including small arms and associated ammunition, rocket propelled grenades, mortar rounds, 107mm rockets, and plastic explosives.” Iran has also permitted the Taliban free movement of foreign fighters through Iranian territory to support its insurgency in Afghanistan.

On October 25, 2007, the U.S. Department of the Treasury designated the IRGC-Quds Force under Executive Order 13382 for providing material support to the Taliban and other terrorist organizations. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Treasury added three Iranian IRGC-Quds Force operatives and one “associate” to its list of global terrorists for their efforts to “plan and execute attacks in Afghanistan,” including providing “logistical support” in order to advance Iran’s interests in the region. The Treasury Department has stated that these designations “[underscore] Tehran’s use of terrorism and intelligence operations as tools of influence against the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.”

Iran’s support for the Taliban was at times short-sighted. For example, the governor of Helmand Province accused the IRGC in 2017 of giving the Taliban weapons to attack Afghanistan’s water infrastructure so that Iran could receive a larger portion of water from the Helmand River. While this was self-serving in the immediate term, such tactics served to weaken the Afghan government and ultimately undermined Afghanistan’s longer-term stability.

In 2018, the U.S. Department of the Treasury sanctioned additional individuals who spearheaded cooperation between the Taliban and Tehran. They included Mohammad Ebrahim Owhadi, a Quds Force operative, who, according to the U.S. government, provided “military and financial assistance” to the “Taliban Shadow Governor of Herat Province,” Abdullah Samad Faroqui, in exchange for Taliban forces launching attacks against the Afghan government.

Additionally, the U.S. government identified Esma’il Razavi, an operative who ran a training camp for Taliban forces in Birjand, Iran, and also “provided training, intelligence, and weapons to Taliban forces in Farah, Ghor, Badhis, and Helmand Provinces.” News reports indicate that Iran directly supported the Taliban offensive against Farah Province in May 2018.

Brigadier-General Esmail Qaani became the head of the IRGC-Quds Force following the death of Qassem Soleimani in January 2020. Qaani has deep contacts and experience in Afghanistan—dating back to the 1980s. After Soleimani’s demise, Iranian media began circulating unconfirmed reports that high-ranking Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) officials perished in a plane crash in Taliban-controlled territory of a Bombardier E-11A electronic surveillance plane, and that one of those officials was involved in the death of Soleimani. Days later, the U.S. government announced two U.S. Air Force pilots were killed in the incident, and there was no indication of hostile action in the downing of the jet.

There has been speculation that this story was produced as part of an Iranian propaganda campaign. Such allegations came on the heels of an increasingly close relationship between Tehran and the Taliban, with Iranian media repeatedly interviewing its officials. Days after the plane crash, the head of U.S. Central Command warned of a “worrisome trend” in intelligence pointing to an uptick in Iran’s malign activity in Afghanistan. This was evidence of the new Quds Force commander seeking to deploy his existing network inside Afghanistan against U.S. forces.

Iran's Destabilizing Double-Game

On February 29, 2020, the U.S. and the Taliban signed a peace agreement in Doha that envisioned a complete U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in exchange for assurances from the Taliban that the group would prevent Afghanistan from becoming a safe haven for terrorists. The agreement was meant to pave the way for negotiations between the Taliban and the Afghan government on a power sharing agreement that would shape Afghanistan’s future.

After the agreement was reached, Iran continued to play a destabilizing double game in Afghanistan, as it sought to ensure that it would retain influence in the country regardless of the outcome of the peace process. On one hand, Iran sought to ingratiate itself with the Afghan government and encouraged various stakeholder factions from across the political spectrum in the government to form a joint committee to ensure a unified front in future talks with the Taliban. Iran even offered to mediate in future talks between the government and the Taliban. In July 2020, Iran announced that it had formulated a "Comprehensive Document of Strategic Cooperation between Iran and Afghanistan" whose fundamental principles are "non-interference in each other's affairs," "non-aggression," and "non-use of each other's territory to attack and invade other countries."

On the other hand, however, Iran maintained contact with the Taliban to retain leverage over the Afghan government and peace process. Moreover, Iran evidently worked to sabotage the peace process by backing more radical elements and splinter groups from the Taliban who opposed negotiations and sought to keep fighting the central government and the U.S. military presence. An August 2020 CNN report revealed that U.S. intelligence agencies assessed that Iran had provided bounty payments to the Haqqani Network, a terrorist offshoot of the Taliban, for attacks on U.S. and coalition forces. The report found that Iran had paid bounties for six Haqqani Network attacks in 2019 alone, including a major suicide bombing at Bagram Air Base in December 2019 that killed two civilians and wounded over 70 people, including four U.S. service personnel. The U.S. ultimately refrained from retaliation for the attack in order to preserve the peace process with the Taliban, but Iran’s role in financing these attacks against the U.S. showed the potential for Tehran to play spoiler through its ties to the Taliban.

Iran was hard hit by sanctions and the COVID-19 pandemic, so it sought to avoid pushing the envelope too hard in terms of proxy confrontation with the U.S., instead pursuing strategic patience in the hopes that the U.S. would withdraw on its own accord. At the same time, by retaining its influence over radical Taliban elements, Iran ensured that it would be able to marshal such forces to reengage in hostilities against the U.S. at a time of its choosing should the U.S. have vacillated on leaving Afghanistan. Iran’s influence over both the Taliban and its most radical elements allowed it to protect against hostilities from Afghanistan in the event of a Taliban takeover.

In July 2021, after years of playing arsonist in Afghanistan, Iran tried to take on the unlikely role of firefighter, hosting a round of peace negotiations that brought together the Afghan government and the Taliban. The talks signaled that with the U.S. departing from the scene, Tehran sought to become a major power broker going forward in Afghanistan. Chairing the talks, Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif hailed the defeat of U.S. forces and called for a political solution to the escalating hostilities between the Afghan government and the resurgent Taliban.

Iran’s diplomatic overtures were too little too late, however. The last-ditch attempt to revive the stalled intra-Afghan peace process broke down for many reasons. The Trump Administration effectively sidelined the Afghan government by bypassing it and entering a bilateral agreement directly with the Taliban in February 2020, signaling that the government would not be a major stakeholder in shaping the country's future trajectory. Further, the Trump Administration telegraphed its determination to withdraw from Afghanistan, securing only vague promises from the Taliban to govern more inclusively and prevent terrorist safe-havens. The U.S. did not attach any conditions to its withdrawal based on progress on the peace process or suitable power sharing arrangements, removing any incentive for the Taliban to negotiate in good faith or make concessions.

Reading the tea leaves, the Taliban opted to wait out the clock on the U.S. withdrawal, convinced that its takeover of Afghanistan was a fait accompli. The Taliban, therefore, dragged its feet on entering negotiations and became bolder on the ground, heavily rearming and reclaiming territory at a rapid clip in the months after the Doha agreement. This confluence of factors—the Taliban’s growing strength, the U.S.’s desire to check out, and the Afghan government’s increasingly apparent weakness—had a demoralizing effect on the country’s military and law enforcement forces, contributing to their unwillingness to fight back against the Taliban’s rapid retaking of two-thirds of Afghan territory, including the seat of government in Kabul, in August 2021.

Iranian officials were cautiously optimistic in the preceding months about the return to power of the Taliban, clinging to the hope that a new Taliban regime would be a different beast from the 1998 perpetrator of the Mazar-i-Sharif massacre.

Iran’s support for the Taliban, though rooted in a marriage of convenience to repel the U.S., won Iran influence with the group it hoped would endure even after the departure of their common foe. Faced with the challenge of governing Afghanistan’s disparate ethnic, sectarian, and tribal factions and seeking to avoid again becoming an internationally isolated pariah, the Taliban then sought to portray itself as a nationalistic, as opposed to strictly Pashtun, force, capable of inclusive governance. As such, it has dialed back its persecution of Shi’a Hazaras, going so far as to appoint a Hazara cleric as a northern district governor.

After the Taliban declared the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, Iran reached out to the Taliban with an olive branch. Newly inaugurated President Ebrahim Raisi issued a statement hailing the U.S. military defeat in which he declared, "Iran backs efforts to restore stability in Afghanistan and, as a neighboring and brother nation, Iran invites all groups in Afghanistan to reach a national agreement." By invoking “all groups,” Raisi was signaling Tehran’s willingness to work with the Taliban.

Tensions between the Taliban and the Iranian regime escalated in mid-2023. At the border of Iran’s Sistan and Baluchestan provinces and Afghanistan’s Nimroz province, in May 2023, Taliban and Iranian forces exchanged fire amid a dispute over water rights. The dispute centers around the Helmand River, which empties into the Helmand swamps on the border with Iran. Iran claims rights to the river, which it depends on for irrigation in the Sistan and Baluchestan province. It has asserted that the Taliban have violated a 1973 agreement that guarantees Iran’s access. Iran alleges that the Taliban is allowing a mere four percent of the agreed amount and has rejected the Taliban’s claim that the reduced flows are due to a lack of rain and drought.

.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox.

Eye on Iran is a news summary from United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI), a section 501(c)(3) organization. Eye on Iran is available to subscribers on a daily basis or weekly basis.