Iranian Infiltration of Africa

Download PDFPage Navigation

The Islamic Republic of Iran advances its interests on the African continent on multiple fronts, employing some of the same tactics Tehran utilizes in the Middle East. Iran is infiltrating Africa not only to spread the regime’s Shiite Islamist ideology and terrorism against Western interests but also to develop political and economic partnerships. This resource, “Iranian Infiltration of Africa,” seeks to show where, when, and how the Islamic Republic has made strides toward its foreign policy objectives and notable failures on the continent.

The first section of this report introduces Tehran’s foreign policy interests on the African continent. The second section provides a historical overview of Iran’s Africa policy, referring to Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s reign from 1953 to 1979. The third section comprises country reports detailing the Islamic Republic’s political, economic, and ideological interests and the presence of Iran-backed terrorist activity in each profiled state. Each country report takes stock of Iranian foreign policy successes and failures and concludes with policy recommendations.

Iran’s Interests on the African Continent

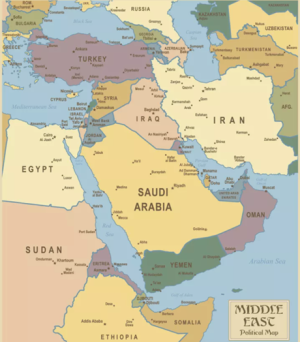

Map of the Middle East (Source: Trip Savvy)

Map of the Middle East (Source: Trip Savvy)

Iran’s interests in Africa run the gamut, from strategic interests in its ability to provide arms routes for the regime’s various proxy wars to Tehran’s more ideological and diplomatic battle with Saudi Arabia over influence on the continent. The Iranian-Saudi dispute has spurred many of Iran’s sectarian activities in Africa. The Islamic Republic has established a clerical network in a bid to radicalize the Shia religion and recruit individuals for terrorist operations, but these sectarian endeavors are only one dimension of Iran’s multifaceted campaign. Iran has notched other victories in Africa, including docking its naval assets at ports in the Red Sea and deploying Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) operatives to the Horn of Africa. Iran remains motivated by the continent’s strategic and diplomatic stakes.

Historically, Iran had strategic interests in East Africa, particularly in the Horn of Africa. Red Sea ports used to serve as a critical link in Iran’s arms distribution network. The Iran-sponsored Houthi rebels in Yemen have been from armed Eritrea via the Red Sea and from Somalia via the Gulf of Aden. When dictator Omar al-Bashir ruled Sudan, the country’s Port of Sawakin and Port Sudan were also common destinations for weapons intended for Palestinian militants, with supply lines running through Sudan, Egypt, and the Sinai Peninsula and into Palestinian territories. Additionally, the Red Sea connects to the Suez Canal, through which weapons may be shipped to the Mediterranean and received at ports in Lebanon or Syria. As land routes through Iraq and Syria are vulnerable to Israeli airstrikes, Iran has sent vessels through the Suez Canal—even on one occasion with a Russian naval escort.

East Africa’s strategic value to Tehran should not be underestimated, even though the region has become more resilient against Iran’s malign activities. Throughout the 1990s, Sudan provided refuge and training for Islamist insurgencies opposed to Western-aligned governments like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Tunisia, and Algeria. Iran transferred arms to the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) in Algeria through Sudan in the early 1990s. Sudan, a U.S.-designated sponsor of terrorism between 1993 and 2020, also cooperated with Iran-backed militias and terrorist organizations, including the Palestinian terrorist group Hamas.

Moreover, Sudan and Eritrea allowed Iran to deploy its naval assets and challenge the Bab al-Mandeb Strait, a vital shipping lane, given that nearly nine percent of the total seaborne oil trade transits. Starting in 2008, Iran deployed naval vessels at Eritrea’s Port of Assab, with the purported mission to combat piracy off the coast of Somalia. In 2012, the regime docked a destroyer at the Port of Sudan on a visit. These docks provided an advantage to the IRGC Navy, whose modus operandi is to menace international shipping to extract leverage.

However, the late 2000s and early 2010s marked the highpoint of Iranian political influence in East Africa, as the U.S., Israel, and Saudi Arabia have accumulated more sway in the region since then. Sudan, Djibouti, and Somalia severed diplomatic ties with Iran in January 2016 under pressure from Saudi Arabia, which had broken relations with Iran after an attack on its embassy in Tehran. Eritrea did not follow suit but allowed the Saudi-led coalition to access its ports and airspace to conduct anti-Houthi operations in Yemen. Thus, after years of estrangement, which saw improved ties with Tehran, Eritrea repaired its relations with Western powers, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. In 2018, it reached a UAE-brokered peace deal with its regional rival, Ethiopia, at Tehran’s expense. Sudan signed the declarative part of the U.S.-sponsored Abraham Accords to recognize Israel in January 2021.

In addition to protecting strategic arms routes and challenging Red Sea shipping lanes, Iran holds geopolitical interests in Africa. Since the inception of the Islamic Republic, Iran and Saudi Arabia have competed for leadership in the Muslim world, including in Muslim African countries. Iran’s activities in Africa have sparked fears it seeks to extend and operationalize its religious footprint in Sub-Saharan Africa as it has done throughout the Middle East in its proxy wars. While neither Iran nor Saudi Arabia have deployed overt military force to change political events in Africa, both use soft power to spread their unique brands of Shia and Sunni Islam.

Iran’s third set of interests on the continent derives from Africa’s sizeable Muslim population. Just over three-quarters of Africa’s approximately 500 million Muslims practice Sufism, a mystic set of practices found in Sunni Islam. These beliefs differ from Iran’s version of Shiism, so Sufis are less susceptible to Iranian weaponization than the ten percent of Africa’s Muslim population who are Shia. The Shia Lebanese diaspora in West Africa, for example, has proven vulnerable to Hezbollah, Iran’s Shia proxy based in Lebanon. In 2013, the U.S. Department of the Treasury sanctioned a network of Hezbollah operatives in Sierra Leone, Senegal, Ivory Coast, and the Gambia, where the group was engaged in massive money laundering operations. Islam’s prevalence in Africa appeals to Tehran because it creates a constituency that sympathizes with Iran’s self-image as the defender of Islam against Western powers.

The Iranian regime’s sectarian interests in West Africa dovetail with its fourth objective: terrorism. Iran spreads its extremist variant of Shia Islam, with a focus on Nigeria, Senegal, and Tanzania. Moreover, Iranian regime officials believe that enmity toward the U.S. can be exploited to coopt groups that adhere to different Islamic movements. The most striking example of an Iran-backed Sunni terrorist group in Africa is al-Shabaab, an al-Qaeda affiliate active in Somalia and East Africa that has conducted multiple deadly attacks against the U.S. With the support of IRGC-Quds Force operatives deployed in Eritrea, al-Shabaab waged a violent insurgency against Somalia’s central government in the mid-2000s.

Iran’s main vehicle for exporting the Islamic Revolution is the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)—and, in particular, its special operations branch, the Quds Force. To export the Revolution, the IRGC employs violence and subversion, especially directed at governments that are aligned with the U.S. and with Israel. The Quds Force commander, Brigadier General Esmail Qaani, was in charge of the Quds Force’s Africa portfolio under his predecessor, Major General Qassem Soleimani. In 2010, Qaani was implicated in the shipment of 240 tons of arms destined for the Gambia but seized in Nigeria. In 2012, the U.S. designated Qaani for his role in financing Quds Force elements in Africa.

In 2020, following Soleimani’s assassination in a U.S. Reaper drone strike in Baghdad, the IRGC-linked Tasnim News published a piece claiming that U.S. interests are vulnerable in Africa and calling on the IRGC to train and arm non-state actors in the region. Quds Force Unit 400 is thought to be one of the units involved in organizing and directing anti-Western and anti-Israel terrorist elements in Africa. A commander named Hamed Abdallahi leads the unit in close coordination with Hezbollah.

From a terrorist financing perspective, the IRGC-linked Fars News Agency published a piece highlighting how transactions in gold facilitate sanctions evasion in Venezuela and stating that this strategy should be applied to Africa. Given that Iran has transferred proceeds from Venezuelan gold to Hezbollah, Iran could seek to exploit Africa’s natural resource wealth as well.

Iran also seeks to break out of its international isolation through diplomatic channels with African countries. Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian was formerly deputy foreign minister for Arab and African affairs and has close ties to the IRGC. He has sought African governments’ diplomatic and economic cooperation to circumvent Western sanctions. Many African states take a neutral position on Iran’s nuclear program, condemning nuclear weapons on the one hand and affirming Iran’s “right” to nuclear energy on the other, disregarding Iran’s noncooperation with International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) investigations. African countries are generally receptive to Iran’s messaging when it comes to its nuclear program, international sanctions, and its knack for denying and deflecting attention from its engagement in terrorism and other malign behaviors.

As a result of Iran’s diplomatic endeavors in Africa, several African countries have allied with Tehran. Tehran’s most important partner on the continent is South Africa, which, in December 2023, filed a genocide case against Israel at the International Court of Justice. South Africa called for lifting all sanctions against Iran in 2007, advocated for Iran’s accession to BRICS in 2017, then joined a unanimous vote in BRICS supporting Iran’s entry in 2023. Other states like Kenya hedge when it comes to Iranian malign activities. Kenya has repeatedly refused to condemn the Iranian regime for its covert activities on Kenyan soil, as Kenya wants to preserve its relations with the Islamic Republic for commercial and technological reasons (discussed below). Despite Africa’s receptivity to Tehran, Iran has fewer than 20 embassies on the continent, underscoring its lack of diplomatic partnerships compared to Western capitals, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Finally, there are economic reasons for Iran to involve itself in Africa. For instance, Sudan, Djibouti, Eritrea, and Ethiopia are experiencing 5-9 percent growth annually. However, because the Horn of Africa prefers financial incentives from Gulf states over cooperating with Tehran, these nations don’t serve as a lucrative alternative to Western markets for Iran. Nor does Africa more broadly provide access to large investment or trade deals. Iran’s foreign ministry expects $2 billion in trade with Africa in 2023, up from $500 million in 2022. Even if Iran realizes its expectations, which seems unlikely, it lacks economic depth compared to its adversaries. UAE-Africa trade, for instance, reached $50 billion in 2022.

In addition to gold, other significant natural-resources in Africa also attract Iran. For instance, uranium deposits exist in many African countries, such as Malawi, Niger, Sierra Leone, Togo, and Uganda. Because former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who served from 2005 to 2013, sought to maximize negotiating leverage by escalating Iran’s nuclear activities, he prioritized relations with these countries to ensure access to uranium.

Historical Overview of Iran’s Africa Policy

Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in Egypt after the Shah's exile from Iran (Source: Radio Farda)

Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in Egypt after the Shah's exile from Iran (Source: Radio Farda)

This section provides a brief historical overview of Iran’s policies towards Africa, from the Shah’s reign (1953-1979) to the current Raisi administration in Iran. It shows how, after the change of regime in 1979, the Islamic Republic of Iran has demonstrated a consistently anti-American foreign policy in Africa through each of its presidents, especially under the Raisi administration.

The Shah’s overall policies towards Africa reacted to the dual threats he saw from the African continent in the 1960s and 1970s: pan-Arabism and communism. Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser was the chief proponent of pan-Arabism, an ideology that calls for unity among Arab nations. He referred to the Shah as a “tool of imperialism” and a “traitor to Islam” because of his relations with the West and Israel. The Shah, in turn, aligned with pro-Western governments in Africa to counter Nasser’s ideological influence. In 1970, Nasser’s death and the rise of the more moderate Anwar Sadat in his place paved the way for Egypt to ally with Iran. Furthermore, the Shah deepened relations with the new Egyptian president, the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, South Africa’s anti-communist apartheid regime, and the Moroccan monarchy to contain communism. He sought these alliances to prevent the spread of communism to the Middle East and curry favor with the U.S. in the context of the Cold War.

The 1979 Islamic Revolution transformed Iran from a secular, Western-oriented monarchy into a Shia theocracy staunchly opposed to the West and Israel. The Islamic Republic’s new foreign policy—geared toward ideological rather than national interests—upended Iran’s diplomatic relations, not only across the Middle East and with the U.S. and Israel but also in Africa. Iran’s strategic interests on the continent were fundamentally reassessed in terms of regime security and the new leadership’s allegiance to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s unconventional system of religious thought. That system’s doctrine, known as velayat e-faqih (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist), endowed Khomeini with the divine right to rule as the preeminent religious and political leader of the Islamic Republic and Muslims worldwide.

Iranian presidents have exhibited notable differences in foreign policy, with some claiming reform and others proposing hardline opposition to the West. However, the president is not the chief decision-maker in Iran; the supreme leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, is. This fact explains the pronounced consistency in foreign policy throughout the history of the Islamic Republic. Further, even the so-called reformist presidents like Mohammad Khatami and Hassan Rouhani have been regime insiders committed to the regime’s revolutionary tenets. Steadfast loyalty to the supreme leader drove the policies of each successive administration, with none going so far as to challenge Khamenei’s strategic vision.

Where the Shah sought to build alliances with Western-aligned African governments, the Islamic Republic viewed these governments as a potential threat and actively sought to undermine them. Like the Shah, the Islamic Republic tied political developments on the continent to its security interests but immediately reversed many of the Shah’s cordial diplomatic relations. For example, after Morocco received the deposed Shah in exile, Khomeini severed diplomatic ties with that country and later recognized the sovereignty of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) in Western Sahara, an area in West Africa that Morocco claims as its sovereign territory. Iran severed diplomatic relations with Egypt in May 1979 in protest of the newly-signed Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt, and tensions escalated when Egyptian President Anwar Sadat gave the Shah refuge in Egypt and refused to extradite him to Iran.

The most striking examples of Iran’s post-revolutionary policy shift in Africa were driven by the regime’s ideological interests, which contrasted with the national interests that motivated the Pahlavi monarchy. The Shah had supplied oil to South Africa despite international sanctions on the latter since the early 1960s for its apartheid policies. The Islamic Republic, in contrast, joined the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) oil embargo against South Africa, slashing oil exports, even though South Africa was then a large importer of Iranian oil. Further, the Islamic Republic claimed to oppose South African apartheid as grounds to express support for the then-outlawed South African political party, the African National Congress (ANC), and severed diplomatic relations with South Africa.

Iran’s revolutionary goals abroad prompted other policies in Africa. By the spring of 1982, Iran had repelled Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Iran. Then, it attempted to press a counteroffensive to claim Iraqi territory, causing the war to continue for another six years. As Tehran at this time was utterly isolated on the international stage, it sought African states’ condemnation of Iraq’s invasion at the UN.

Throughout the 1980s, Iran intensified its religious outreach on the continent through its revolutionary goals, implementing an effort to build a Shia clerical network that has since been operationalized for several aims, including terrorism. A 1984 U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) declassified report revealed that Iran’s Ministry of Islamic Guidance sent clerics to Africa to encourage Shia Muslims to resist what they viewed as illegitimate governments. The clerics used ideological propaganda to instill in their followers that it was their religious duty to establish Shia-dominated governments loyal to the supreme leader of Iran. The CIA’s report cited eyewitness accounts from hundreds of students from Ghana, Mali, Mauritania, Nigeria, Niger, and Senegal attending theological institutions in Iran.

The Islamic Republic gained its first foothold in Africa in Sudan as the latter’s relations with the West deteriorated after Omar al-Bashir’s rise to power in 1989. In 1991, Bashir attended a conference in Iran intended to promote the Islamic Revolution and undermine the U.S.-sponsored Middle East peace process. This event conveyed the regime’s intention to continue to export its revolution despite eight costly years of war with Iraq. In December 1991, Iranian President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani traveled to Sudan and declared, "The Islamic Revolution of Sudan, alongside Iran's pioneer revolution, can doubtless be the source of movement and revolution throughout the Islamic world." Both Bashir and Supreme Leader Khomeini derived the legitimacy of their rule from Islamic and revolutionary ideologies, making the two militant Islamic regimes natural partners. Both became state sponsors of terrorism and developed relations with Hamas and other U.S.-designated terrorist organizations.

However, Iran’s influence in East Africa was weakened during Mohammad Khatami’s 1997–2005 administration as African countries’ relations with the U.S. improved. Most critically, the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks precipitated warmer relations between the U.S. and African countries, such as Ethiopia, Djibouti, Somalia, Kenya, and even Sudan—each of which cooperated with American counterterrorism objectives. With the exception of Eritrea, which was at war with Ethiopia at the time, East Africa primarily aligned itself with the West. Still, Khatami visited Sudan in 2004 and Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Mali, Benin, Zimbabwe, and Uganda in 2005, his last year in office.

The virulently anti-Western and anti-Israel Mahmoud Ahmadinejad became president of Iran in 2005. Once in office, he amplified the regime’s rhetoric about American exploitation of Africa’s resources. As the face of Iranian public diplomacy, he attempted to shame the U.S. and presented Iran as a global leader against oppression. His pursuit of allies in Africa intended to achieve moral and diplomatic cover for Iran’s nuclear and terrorist activities while also compensating for Iran’s then-deteriorating relations with Europe and Asia. He sought to immunize the Iranian economy against Western sanctions and undercut international efforts to isolate the regime.

However, he faced challenges with African countries, most favoring the West. Iran notched a diplomatic victory in 2006 when it attended the African Union (AU) summit as a guest of honor. Still, Ahmadinejad’s policy, if not his anti-American rhetoric, largely failed to achieve significant success—except for with Sudan and Eritrea. In late 2010, following Ahmadinejad’s state visit to Uganda, each of the African members of the UN Security Council (Gabon, Nigeria, and Uganda) voted in favor of sanctions against Iran for its nuclear program. The vote resulted in UN Security Council Resolution 1929, further underscoring Tehran’s isolation on the continent.

The Rouhani administration, which took power in 2013, prioritized a nuclear deal with the West and downgraded Africa as a priority. Rouhani focused on outreach to the U.S., China, Russia, the U.K., France, and Germany (also known as the P5+1). He never traveled to Africa during his tenure, and the only presidents of African countries who visited Iran were those of Ghana, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. After the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was signed in 2015, Africa didn’t feature in Iran’s efforts to open its economy to the world. Despite the JCPOA, Iranian-African trade relations stagnated because Rouhani prioritized Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Trade with Sub-Saharan Africa reached an all-time low in 2015 and never exceeded 1 percent of Iran’s total trade during Rouhani’s time in office.

Nevertheless, Rouhani began paying more attention to Africa after Iran’s tensions with the U.S. ratcheted up during the Trump administration. The U.S. withdrew from the JCPOA in 2018. Iran then sought ways to circumvent U.S. sanctions with the help of African companies. In March 2020, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced sanctions against several South African companies for their illicit Iranian oil trade involvement.

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi receives an honor guard during his state visit to Nairobi in July 2023 (Source: CNN)

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi receives an honor guard during his state visit to Nairobi in July 2023 (Source: CNN)

The 2021 election of Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi marked another turn in Tehran’s foreign policy. Iran’s centers of power aligned in opposition to détente with the West and in favor of intensifying Iran’s nuclear program and terrorist activities. To compensate for the costs of this escalation, Iran sees Africa as an alternative to Western markets. Raisi’s July 2023 trip to Kenya, Uganda, and Zimbabwe—the first trip to the continent by an Iranian president since Ahmadinejad went in 2013—is evidence of Iran’s re-prioritization of Africa. Raisi has viewed Africa as an element of the supreme leader’s concept of a “resistance economy” to neutralize sanctions. Iran’s trade with the African continent is small compared to its oil trade with China because Africa complies with U.S. sanctions on Iran’s oil sector whereas China does not. The ongoing economic relations between Iran and Africa are meant to stabilize Iran’s political partnerships, essential to Iran’s wide array of endeavors on the continent.

Conclusion

Iran’s relations with Western capitals have significantly deteriorated due to Iran’s support for Russia’s war against Ukraine, its brutal human rights violations, its rapidly advancing nuclear program, its active threats to foreign nationals on foreign soil—including current and former U.S. officials. Additionally, its ongoing drone and rocket attacks against U.S. forces in the Middle East, and its decades of financing and arming Hamas and other terrorist organizations that destabilize the region, have contributed to Iran’s isolation.

Under the supreme leader’s direction, Iran’s hardline foreign policy establishment has remained intent on subverting U.S., Israeli, and Saudi influence worldwide. Africa is no exception. Even the reportedly more moderate administrations of Khatami and Rouhani, which sought to ease tensions with the West, viewed Africa as an important ideological battlefield. They gave less attention to Iran’s political and economic ties with African countries than the Ahmadinejad and Raisi administrations, but continued to promote the Islamic Republic’s radical version of Shia Islam, which demands loyalty to the supreme leader and injects anti-Western and anti-Israel sentiment. In contrast, the Ahmadinejad and Raisi administrations deprioritized relations with the West and turned to Africa for diplomatic support and sanctions relief. If the past is prologue, the Raisi administration will face an uphill battle on the continent, especially as it vies for influence against its geopolitical and sectarian rivals.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox.

Eye on Iran is a news summary from United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI), a section 501(c)(3) organization. Eye on Iran is available to subscribers on a daily basis or weekly basis.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox

The Iran nuclear deal is done. And the world's biggest companies have already visited Tehran ready to strike a deal when sanctions end. These businesses will add even more to Iran's bottom line. And that means continued development of nuclear technologies and more cash for Hamas and Hezbollah.