Iran’s Relations with African Countries

Download PDFPage Navigation

Read Iranian Infiltration of Africa

The following country reports provide historical context and discuss recent developments in Iran’s relationship with each nation. They aim to expose Tehran’s political, economic, and ideological interests in each country and determine whether it has advanced those interests. Africa is not the main arena of Iranian terrorism and destabilization to undermine Western security interests; the Middle East is. But Tehran has applied the same methods to its Africa portfolio to the same ends. Therefore, each report also traces Iran’s subversive activities in the country in question, focusing on the IRGC and Hezbollah.

Algeria

Algerian Foreign Minister Ahmed Attaf meets with Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi in Tehran (Source: Tehran Times)

Algerian Foreign Minister Ahmed Attaf meets with Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi in Tehran (Source: Tehran Times)

Overview: Algeria is a North African country that borders Morocco, its rival. The Tindouf refugee camp in Algeria at the border with Morocco, Mauritania, and Western Sahara doubles as an operational and recruitment center for the Polisario Front. This Algerian-backed militia receives support from Tehran and Hezbollah to contest Morocco’s Western Sahara sovereign claims. Iran’s support for the Polisario Front and its cooperation with Algeria serve as vectors to impose costs on Morocco, which joined the Abraham Accords in December 2020. Algeria also serves as a ripe ideological breeding ground with a long history of anti-Israel sentiment and has taken measures to obstruct Israeli diplomatic initiatives on the continent. Algiers stands with Tehran on issues ranging from the latter’s nuclear program to its recent charm offensive in the Middle East.

Historical Background: Algeria, a former French colony that gained independence in 1962, sympathized with the Islamic Revolution due to the Revolution’s ostensibly anti-imperialistic stance. This sympathy—framed in terms of resistance against Western powers—contributed to Algeria becoming a palatable interlocutor to Iran throughout the November 1979 Iran hostage crisis after armed followers of Khomeini seized the U.S. embassy in Tehran and captured the diplomats inside. The U.S. severed diplomatic relations with Tehran and eventually settled on the Algeria-brokered Algiers Accord in January 1981, which freed the hostages.

Notwithstanding this history of ideological similarity, Algerian-Iranian diplomatic relations were strained in the early to mid-1990s when Iran began supporting the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS). This Algerian Islamist party started an insurgency in 1992 after the military canceled elections and dissolved the party. The FIS was on the verge of winning the elections and framed the military’s intervention as a U.S.-backed coup. By appealing to anti-imperialist ideas and Islamic religious and cultural identity, the FIS was able to recruit members and attract Tehran’s attention. The FIS became a vehicle for Tehran to win ideological points and undermine U.S. regional interests.

In 1993, Algeria accused Tehran of backing the FIS and severed diplomatic relations. The following year, the New York Times reported that Sudan was allowing its territory to be used as a transit point for Iranian weapons destined for the Algerian guerillas and was the site of training facilities. The guerillas also received training in Lebanon, suggesting Hezbollah’s involvement. The FIS would wage an insurgency against the government for the next decade within the context of a civil war involving various other radical Islamist groups. According to some estimates, the civil war claimed 200,000 civilian lives by the end of the 1990s.

Political Interests: Iran’s first political interest in Algeria is obtaining Algeria’s support for Iran’s nuclear program. In 2000, diplomatic relations between Algeria and Iran were reestablished, one year after President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s rise to power. After Algeria issued statements claiming that Iran’s nuclear program was exclusively intended for peaceful purposes, in 2007, Iran offered Algeria support in developing its civilian nuclear program. Although Algerian officials toured a uranium conversion facility in Esfahan soon after Iran made the offer, Algeria did not ultimately accept it.

Iran’s second goal in Algeria is to ensure that the latter continues to align with Iran-backed Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad. In 2012, Algeria and Iran were the only countries in the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) that opposed that body’s decision to suspend Syria’s membership over its brutal armed response to a popular uprising in Syria. In 2022, Algeria supported Syria’s return to the Arab League. It also benefits Tehran that Algeria has refused to join the Saudi-led coalition fighting the Houthis in Yemen.

Thirdly, Iran stokes tensions between Algeria and Morocco to counter Israel. In August 2021, Algeria severed diplomatic relations with Morocco, citing Morocco’s alleged use of Pegasus spyware, its support for a separatist group in Algeria, and its failure to uphold bilateral commitments over Western Sahara. Iran welcomed the decision, claiming it showed Algeria’s support for the Palestinian people in the context of the newly signed Abraham Accords, which included Morocco. Algeria also obstructs Israel’s diplomatic efforts on the continent. In February 2023, an Israeli diplomat attending the African Union (AU) as an observer was expelled, a move that Israel blamed on Algeria, South Africa, and Iran. Israel obtained its observer status in 2021 despite Algeria’s objection that it would violate the AU’s previously adopted pro-Palestinian resolutions. In 2023, Iranian Foreign Minister Abdollahian praised Algeria’s commitment to the Palestinians.

Algeria also supports Iran’s recent charm offensive in the Middle East, which includes diplomatic outreach to its arch-rival, Saudi Arabia, and other Arab states in the Persian Gulf. On a July 2023 trip to Tehran, Algerian Foreign Minister Ahmed Attaf met with senior regime officials, including President Ebrahim Raisi, and indicated his preference for Iran’s regional integration. Attaf characterized the Chinese-brokered Saudi-Iranian normalization agreement from a few months before this meeting as a “positive movement” in Arab-Iranian relations. Abdollahian, for his part, expressed his government’s interest in expanding cooperation with Algeria in various non-military fields.

While relations between Saudi Arabia and Algeria were tense due to Saudi Arabia’s ties with Morocco, Amwaj Media finds that Saudi Arabia and Algeria “have taken important steps towards détente,” mainly since President Abdelmadjid Tebboune came to power in December 2019. The Saudi-Iranian normalization agreement could open Algeria to pursue relations with Saudi Arabia and Iran. In contrast, Iran’s proxy war in Yemen against Saudi Arabia led Saudi Arabia to pressure African countries to sever ties with the Islamic Republic.

Economic Interests: In 2007, Ahmadinejad traveled to Algeria, urging Algerian companies to engage in cooperative trade and investment agreements with Iranian companies in the automobile, petrochemical, and gas sectors. Over the following year, bilateral trade doubled to $50 million. In 2009, Algeria and Iran—the world’s second and sixth largest natural gas producers, respectively—discussed forming a gas-producer cartel similar to the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). That year, they coordinated oil production cuts. In 2016, Iran Khodro established an automobile manufacturing plant in Algeria. In 2018, Iran exported 29 million dollars worth of goods to Algeria. Iran has expressed optimism about continuing to increase bilateral trade, with Iranian media reporting that between May 2023 and July 2023, Iran exported twice the quantity of non-oil products to Algeria compared to that period in the prior year.

Ideological Interests: Iran has targeted Algerian Shia with propaganda since the early 1980s. Tehran amplified its anti-Israel messaging in Algeria during the 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah, attracting some Algerians to travel to the Middle East to convert to Shiite Islam and then build a clerical network in their home country. In early 2015, Iranian sectarianism intensified as a result of Amir Mousavi, who is believed to have been an Iranian intelligence agent and brigadier general in the IRGC, being stationed as cultural attaché at the Iranian embassy in Algiers. Known for supporting Hezbollah and the Popular Mobilization Force (PMF) in Iraq, Mousavi set up “cultural exchange programs that aimed to spread Shiism through mosques and educational institutions.” In 2018, Moroccan Foreign Minister Nasser Bourita alleged that Mousavi “supervis[ed] the spread of Shia [religion] in the Arab world and in Africa" and served as a liaison between Hezbollah, Algeria, and the Polisario Front.

These soft-power initiatives paid off. Between 2000 and 2022, the total number of Shia with sympathy for the regime in Tehran, if not outright allegiance, reportedly doubled. Further, Algeria has sought to provoke a backlash against Israel in response to Morocco’s entry into the Abraham Accords in December 2020. Algerian security services blame Israel and Morocco for supporting separatist groups in Algeria and perceive Morocco’s relations with Israel as a security threat. The prospects for a joint Moroccan-Israeli military base south of Melilla, situated on the Mediterranean Sea to the north of Morocco, probably heightened this perception. In 2022, Israel sold drones to Morocco. Tehran has taken advantage of this situation to inculcate loyalty and cultivate pro-Palestinian views among Algerian Shia.

Terrorist Activity: The IRGC and Hezbollah maintain ties with the Polisario Front, an independence movement seeking to realize its sovereign claims over Western Sahara. Since Morocco and Mauritania established control over Western Sahara after Spain unilaterally withdrew from the area in 1975, Rabat has remained in conflict with the Polisario Front. Algeria provides sanctuary for Polisario Front members and may also offer arms, but it has denied the latter charges.

Hezbollah’s support for the Polisario Front dates back to 2016 when Hezbollah established the Committee for the Support of the Sahrawi People in Lebanon. The following year, Kassim Tajideen, a U.S.-designated senior operative in Hezbollah’s Africa financing arm, was arrested on an Interpol warrant at Casablanca airport for fraud, money laundering, and terrorism. Morocco extradited Tajideen to the U.S., where he pled guilty to roughly $1 billion in unlawful transactions. According to Moroccan Foreign Minister Nasser Bourita, Hezbollah retaliated for the extradition by transferring a variety of surface-to-air missiles (SAM) to the Polisario Front under the supervision of the Iranian embassy in Algiers.

Since 2017, the IRGC and Hezbollah have allegedly used the Tindouf refugee camp in Algeria to provide the Polisario Front with military training. Hezbollah deployed advisors to assist the group as it upgraded its anti-air capabilities to deter the Moroccan Air Force. Consequently, Morocco terminated diplomatic relations with Iran in 2018. A Polisario Front member claimed in 2022 that Algeria would facilitate Iran’s transfer of drones to the group, though it is unclear if such transfers occurred.

Conclusion: Algeria opposes the Abraham Accords, partly because they resulted in the U.S.’s recognition of Morocco’s sovereignty over Western Sahara. Algeria, which already receives Russian arms, could look to Iran to bolster its capabilities, mainly if the Israeli-Moroccan security partnership deepens. The U.S. should, therefore, consider how facilitating a deeper Israeli-Moroccan partnership could benefit both Israel and Morocco, which share an interest in countering the Islamic Republic. Additionally, the U.S. must take the necessary steps to support Morocco’s capabilities to disrupt the flow of arms and training into the region, especially as Iran aims to escalate vis-à-vis Morocco because the latter joined the Abraham Accords. To those ends, the U.S., Israel, and Morocco should share intelligence and monitor the supply routes that could be used to transfer weapons to the Polisario Front or Algeria, including the Mediterranean Sea.

Central African Republic (CAR)

Overview: Known for its weak and unstable central governance, including multiple coups, the Central African Republic (CAR) provides a fertile breeding ground for terrorist activity. CAR also has gold and diamond mines, which attract illicit actors, including the Russian private military contractor, the Wagner Group. The IRGC–Quds Force remains active in CAR but does not appear to have sought illicit financing in Africa through a stake in the aforementioned mineral resources.

Historical Background: The Seleka group, a coalition of primarily Muslim armed organizations, seized control of CAR’s government in 2013, ousted President Francois Bozize, and brought Michel Djotodia into power. That same year, President Djotodia announced that the Seleka group would be disbanded, though many of the militia commanders did not comply with his order. Only a few months later, Djotodia resigned, reportedly in a bid to end the violence between Christian and Muslim militias that had engulfed the nation since his rise.

Terrorist Activity: Amid this sectarian strife, the IRGC-Quds Force has recruited and worked with Ismael Djidah—a former member of Seleka—to target Western, Israeli, and Saudi interests in several countries. Djidah, who is believed to have been recruited by the IRGC-Quds Force in 2014, allegedly received tens of thousands of dollars from the IRGC-Quds Force on his trips to Lebanon, Iraq, and Iran. He was arrested in his home country of Chad in April 2019.

Djidah’s former boss, former CAR President Djotodia, also reportedly assisted the IRGC-Quds Force’s and Djidah’s efforts to carry out attacks against Western interests. However, the extent and timing of his contributions were unclear based on reporting. Furthermore, IRGC-Quds Force Unit 400 has recruited, trained, and armed the terrorist group Saraya Zahara in CAR to coordinate cells in Chad and Sudan and stand up new ones in Cameroon, Ghana, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Niger. There are up to 300 militants in the network that take their orders from cells in CAR. After his arrest, Djidah admitted that he had worked with the IRGC-Quds Force to form Saraya Zahraa. Between 2017 and 2018, Djidah recruited militants from rebel groups in CAR for firearm training at Iran-run camps in Lebanon, Iraq, and Syria.

Conclusion: Iran-backed terrorism is a potential threat to Western interests in failing and weak states. CAR falls into that category, with the current president, Faustin-Archange Touadéra, showing an inability to prevent terrorism from metastasizing and to provide his citizens with necessities. According to a U.K. delegate to the UN, some progress was made in electoral reform in CAR, but terrorism and violence remain pervasive. The IRGC-Quds Force’s activities in CAR have not made headlines like the Wagner Group’s human rights abuses in the country have. Still, the country’s instability and weak central government remain conducive to the IRGC’s operations.

Eritrea

Overview: Bordering Djibouti, where the U.S. has a naval base at the mouth of the Bab al-Mandeb Strait, Eritrea is strategically positioned to allow external navies to challenge a key international shipping lane. In the mid-2000s, Iran reached an agreement with Eritrea that gave Tehran’s naval assets extended access to the Port of Assab. While Iran claimed to be combatting piracy, its true intentions were clear: to counter the U.S. naval presence in the region, to seek leverage by endangering passage through the Bab al-Mandeb Strait as the Houthis have done from Yemen by targeting international shipping, particularly vessels headed towards Israel, and to establish the logistical routes needed to transfer weapons to militants in Egypt for onward transfer to the Palestinian territories. Iran’s naval assets in this region gave the regime a degree of strategic depth that would allow it to target shipping and conduct operations further from its territorial waters, a core military objective.

Historical Background: Iranian-Eritrean relations were historically influenced by Eritrea’s alignment with the West in the 1990s and its international isolation, which resulted from its war with Ethiopia. After Eritrea gained independence from Ethiopia in 1993, it aligned with the U.S. and Israel against Sudan, then Tehran’s ally in East Africa. Eritrea received U.S. and Israeli support to contain Sudanese dictator Omar al-Bashir’s anti-Western, Islamist military regime. Eritrea and Sudan backed armed opposition groups in each other’s countries, leading to tensions between Eritrea and Iran, given that Tehran sought to protect Bashir’s rule.

A 1998 border dispute between Ethiopia and Eritrea led to the latter’s isolation on the international stage. Although hostilities officially ended in late 2000 with the signing of the Algiers agreement, which established the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC) to draw up the new borderlines, conflict over the border would persist for the next two decades. In 2003, Ethiopia rejected the EEBC demarcation line. Still, because the U.S. viewed Ethiopia as its chief Global War on Terror partner in the Horn of Africa, it did not censure Ethiopia. In 2005, a Hague Commission blamed Eritrea for the 1998 border dispute, which further underscored Eritrea’s isolation at this time.

In 2006, the year in which Iran attended the African Union (AU) as a guest of honor, Ethiopia invaded Somalia and spearheaded U.S.-backed efforts to oust Somalia’s Islamist government. Eritrea, in turn, supported Somali Islamist insurgents against the subsequently formed Ethiopian-backed government. Some of the deposed Islamists took sanctuary in Eritrea and received support there as they sought to regain power. These actions deepened Eritrea’s international isolation. The U.S. Department of State banned arms sales to Eritrea due to concerns it was aiding terrorists in the Horn of Africa. The UN also found that Eritrea supported militant Islamists in Somalia, and so it imposed an arms embargo on the country.

Therefore, the border dispute between Ethiopia and Eritrea had a major impact on Eritrea’s foreign relations. Eritrea opposed the U.S., which was working in concert with Ethiopian interests. Given that Eritrea’s relations with the West were in shambles, Iran was able to expand its influence. In 2008, an Eritrean opposition website alleged that Iran transferred long-range missiles to Eritrea’s Port of Assab. That year, Iran began docking its warships at the port. Additionally, Iran deployed IRGC-Quds Force operatives, naval officers, and military experts to Eritrea to support Eritrea’s proxy war in Somalia. In 2009, ostensibly in exchange for Eritrea’s open statement of support for Iran’s nuclear program, Iran deposited $35 million in Eritrea’s Central Bank.

In 2012, despite Iran’s naval deployment and despite the IRGC-Quds Force's presence to assist in the planning and coordinating of Eritrea’s subversive operations in Somalia and Ethiopia, Eritrean officials allowed Israel to deploy naval and intelligence assets in its territorial waters. Iran and Israel, therefore, were vying for permission to establish military positions at Eritrea’s ports. In addition to a listening post, Israeli submarines and ships were present in the Dahlak Archipelago to monitor Iranian activities. Given that Israel and Iran both deployed naval capabilities to Eritrea at this time, Eritrea was a potential flashpoint for conflict between Israel and Iran.

That same year, Ethiopia, frustrated by Eritrea’s support for rebel groups in its territory, launched a ground offensive into Eritrean territory, killing several Eritrean military personnel. However, this still did not turn international opinion in Eritrea’s favor. Eritrea would remain isolated until the outbreak of war in Yemen in 2015, which allowed it to reverse course by joining the Saudi-led coalition of states fighting the Iran-backed Houthis. In exchange for allowing access to the Port of Assab and its airspace, Eritrea received an unspecified amount of Saudi and Emirati funds. Additionally, Sudanese contingents moved through the Port of Assab into the Yemeni theatre, and the UAE’s air force flew sorties out of Eritrea. Eritrea itself contributed 400 troops to deploy in Emirati units.

Eritrea’s international position improved in April 2018 when the UAE brokered a deal between Eritrea and Ethiopia that effectively ended the two countries’ border dispute. The agreement restored Eritrea’s relations with Somalia, resolved its conflict with Djibouti, and lifted some international sanctions due to Emirati lobbying. On some accounts, Eritrea began providing military aid to Ethiopia as part of the deal that would be used to degrade the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), their shared adversary, which had ruled Ethiopia for almost three decades and partnered with the U.S.

Political Interests: The war in Yemen was the initial impetus for Eritrea’s positive relations with Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The war effectively forced Eritrea to choose its partner—either Riyadh or Tehran—and it chose Riyadh. However, given the cessation of hostilities between the Houthis and Saudi Arabia, partly due to the Chinese-brokered normalization agreement between Iran and Saudi Arabia, there will likely be less pressure from Saudi Arabia on Eritrea to avoid relations with Tehran. Saudi Arabia appears intent on preventing another escalation with the Houthis, mainly as it focuses on its economic development. This initiative could be jeopardized by cross-border Houthi missile and drone strikes. Saudi Arabia did not participate in the U.S. and U.K. airstrikes against Houthi targets in January 2024. If hostilities flare up again in Yemen between the internationally recognized government and the Iran-backed Houthis, Iran’s interest in Eritrea will be to ensure that Eritrea does not allow the Saudi-led coalition to conduct anti-Houthi operations from Eritrea.

When Saudi Arabia was under regular cross-border attacks from the Houthis, Eritrea angered Saudi Arabia in 2017 by maintaining diplomatic relations with Qatar, despite Qatar’s support for terrorist groups and its warm relations with the world’s leading state sponsor of terrorism, the Islamic Republic. Eritrea did not join the Saudi-led diplomatic and economic embargo against Qatar. The Eritrean government, however, backed a Saudi censure of Qatar, saying, “[the censure was] one initiative among many in the right direction that envisages full realization of regional security and stability.” In 2018, Saudi Arabia welcomed Eritrea and Ethiopia to a summit in Riyadh, where the two former rivals signed agreements building on the UAE-brokered peace deal from earlier that year. Eritrea’s relations with Saudi Arabia appear to be in a more advanced stage than Iran’s. Saudi Arabia’s ability to offer various forms of financial compensation likely continues to entice Eritrea.

Conclusion: Eritrea became estranged from the U.S. in the mid-2000s due to its support for terrorist organizations in Somalia and due to its efforts to destabilize Ethiopia, its adversary, and the U.S.’s counterterrorism partner. It moved closer to Tehran, but the outbreak of the Yemeni civil war in 2015 allowed Eritrea to part ways with Iran. The UAE-brokered peace deal in 2018 further guards against Iranian infiltration, as it restored Eritrea’s positive standing internationally, making Iranian support less critical. However, Tehran’s historical ties with the former pariah state should not be understated. Eritrea may be increasingly open to improving relations with Iran, given that the March 2023 Saudi-Iranian normalization agreement took the pressure off Eritrea to remain distant from Tehran. Therefore, Tehran’s use of Eritrea’s ports to smuggle weapons must be closely monitored. To that end, Combined Task Force 151, a counter-piracy 38-nation naval partnership, must implement tracking and interdiction efforts that target Iranian weapons shipments through the Red Sea.

Ethiopia

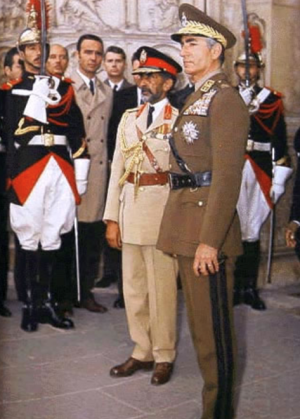

Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie and Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in Ethiopia (Source: Iran Politics Club)

Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie and Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in Ethiopia (Source: Iran Politics Club)

Overview: Ethiopia is one of Africa’s fastest-growing economies. Over the past two decades, Iran’s exports to Ethiopia increased at an annualized rate of 6.68 percent, reaching $1.5 million in 2021. In addition to these burgeoning economic ties, Iran has become a security partner to Ethiopia’s Abiy administration since the start of a civil war in November 2020 between the Ethiopian government and the Tigrayan rebels. Ethiopia’s longstanding ties with the U.S. and Europe were damaged because of Abiy’s brutal military campaign against the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which ruled Ethiopia for over three decades and acted as an important partner in the U.S.-led Global War on Terror in East Africa.

Historical Background: Under the Shah, Iran allied with pro-Western Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, who ruled Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. A Soviet-backed military coup ousted Selassie in 1974, causing Iranian-Ethiopian relations to deteriorate. In 1977, Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam came to power in Ethiopia and implemented the Ethiopian Red Terror, a violent purge of his political rivals. That year, the Shah backed Somali dictator Mohamed Siad Barre in the year-long Ogaden War against Mengistu’s Ethiopia to prevent Soviet penetration.

After the Islamic Revolution, Iran’s relations with Ethiopia’s pro-Soviet military junta, also known as the Derg, improved. Mengistu sided with the Islamic Republic, establishing bilateral relations and opposing the U.S. Moreover, he took Iran’s side in condemning Iraq’s invasion.

In 1991, Ethiopia’s military junta fell, and the TPLF took power, shepherding better relations with the West. After the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania, the U.S. re-prioritized the Horn of Africa and formed closer relations with the TPLF. Following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks against the U.S., additional American military aid was surged to the TPLF, much of which was directed to counterterrorism efforts in Somalia. Israel also contributed military aid to Ethiopia’s counterterrorism program. In 2009, Israeli Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman visited the country.

Ethiopia was a reliable U.S. partner throughout the Global War on Terror. In 2018, however, a change in Ethiopia’s leadership called into question this arrangement. Abiy Ahmed took power, ending the TPLF’s almost thirty-year reign. The TPLF was forced to relocate its operations to the Tigrayan region, where it is still based. The UAE then brokered a deal between Ethiopia and Eritrea in which both states agreed to cease hostilities towards each other.

Abiy’s rise to power marked a turn in the political fortunes of the TPLF. Its standing in the government was diminished as the new administration removed high-profile Tigrayan officials, whom it accused of corruption and repression, from their posts. Abiy sought to institute reforms to the federal system of government that would curtail the Tigray region’s influence. In late 2020, these tensions came to a head when the TPLF attacked the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF), triggering a civil war. Abiy’s brutal response as commander-in-chief of the ENDF caused Western capitals, including the U.S., to withdraw support for him.

Political Interests: In the absence of American support, Abiy sought military assistance from Tehran. The Iranian regime likely noticed a rift between Ethiopia and the U.S. after Washington demanded that Abiy end his military campaign in May 2021. Ethiopia was angered because it viewed the Tigrayan rebels as responsible for the war and control of the Tigray region as integral to its security. After the rebels took control of Mekelle, the capital of the Tigray region, in June 2021, Iran began sending the Mohajer-6 unmanned combat aerial vehicle (UCAV), one of its most advanced drones, to Ethiopia to put down the uprising. The U.S. Treasury Department confirmed the transfers in an October 2021 sanctions package targeting Iran’s drone proliferation network. The U.S. Department of State noted that the transfers violated UN Security Council Resolution 2231, which requires the Council’s approval to import and export certain weapon systems to and from Iran. However, because that provision of Resolution 2231 expired in October 2023, Iran now has legal cover for its drone exports, which could result in more shipments to Ethiopia.

However, Iran’s ability to influence the Abiy administration is not a foregone conclusion. Iran competes for influence in Ethiopia with the UAE, which also has positive relations with the Abiy administration. The UAE, for instance, trained Abiy’s forces and directed drone strikes against Tigrayan positions. Emirati support flights regularly trafficked supplies from the UAE, including the Chinese-made Wing Loong drone, which was delivered to Ethiopian air bases by the UAE throughout the civil war. Ethiopia’s dependence on the UAE likely checks Iranian influence.

Terrorist Activity: In the fall of 2020, Iranian intelligence operatives activated a sleeper cell in Addis Ababa to attack the Emirati embassy and gather intel on the U.S. and Israeli embassies. Ethiopia uncovered the 15-person cell and a cache of weapons and explosives and thwarted the plot. The East African country didn’t blame Iran for the alleged plot. Still, U.S. and Israeli officials indicated it was part of a broader effort to seek revenge for the assassinations of high-ranking Iranian officials. The Emirati embassy might have been targeted due to the UAE’s normalization of ties with Israel in September 2020.

Conclusion: The civil war in Ethiopia ended in November 2022, as both officials from the Abiy administration and the Tigray region agreed to a peace deal contingent upon the disarmament of the Tigrayan rebels. In March 2023, Ethiopian lawmakers revoked the TPLF’s designation as a terrorist group, signaling that the peace deal was durable. The U.S. should no longer seek to impose costs on the Abiy administration for its brutal conduct during the war because doing so would force Ethiopia further into a nascent security partnership with Iran. The proliferation of drones in this volatile region could further destabilize it. Therefore, the U.S. Department of the Treasury should publicly identify and sanction the Iranian actors involved in producing and increasing drones in Ethiopia and the Ethiopian actors responsible for their procurement.

Kenya

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi and Kenyan President William Ruto in Kenya in 2023 (Source: CNN)

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi and Kenyan President William Ruto in Kenya in 2023 (Source: CNN)

Overview: Located on the shore of East Africa, Kenya is a gateway into the continent. Indeed, its major port in Mombasa is a critical transit hub. It is a relatively stable country, making it a safe bet for foreign investment. The former British colony prioritizes its relations with the U.S., but Iran has achieved key ideological goals in Kenya, allowing it to commission various anti-Western plots. The sheer volume of thwarted Iran-linked plots and arrests indicates that Iranian clandestine activity—targeting U.S., Israeli, Saudi, and British interests in the country—is significant and ongoing.

Historical Background: Kenya was a fixture in the Ahmadinejad administration’s African outreach. In 2009, Ahmadinejad traveled to Kenya to solicit trade and investment from the East African country. It was the first Iranian presidential delegation to Kenya since President Rafsanjani traveled there in 1996. Ahmadinejad’s team persuaded Kenyan officials to deepen bilateral relations, and the two nations agreed to establish a shipping route between Bandar Abbas and the Port of Mombasa. Kenya also, at this time, allowed Iran to set up a commercial center in Nairobi. Further, Kenya reportedly sought Iranian technical advice on developing a nuclear program and had already employed Iranian companies to build hydroelectric and gas-powered plants in the country.

After the Trump administration withdrew the U.S. from the JCPOA, Iranian companies contacted Kenya. In 2019, Kenya engaged in talks with them over sharing water management, environmental protection, and renewable energy technology but did not reach any publicly reported agreements. Kenya’s foreign ministry released a statement in January 2021 promoting mutual trade and technological ties and noting that a delegation of Iranian tech companies would travel to Kenya to discuss cooperation in various fields. Still, it was not clear that the delegation ever went to Kenya. The lack of a public record of business deals at this time indicates that they were probably not a priority for President Rouhani.

The Raisi administration continued to pursue economic relations with Kenya as it sought alternatives to Western markets. The Iranian regime downgraded nuclear diplomacy and accelerated the nuclear program, making such options more critical. In 2023, Raisi traveled to Kenya, where he visited Iran’s House of Innovation and Technology, an Iranian network of knowledge-based companies. According to IRGC-linked media, this center comprises more than 35 Iran-based companies that export products to Kenya. During this visit, Kenyan President William Ruto announced that Iran would set up an automobile manufacturing plant in the port city of Mombasa and requested greater access to Iranian tea, meat, and agricultural markets and trade routes through Iran to Central Asia. The two foreign ministers signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) on information technology, fisheries, livestock, and investment promotion.

Political Interests: Kenya is a foreign policy priority for Iran, as Raisi’s recent trip shows. Meanwhile, Kenya seeks to preserve its relations with the West and Iran, so it tends to avoid making statements critical of either. Kenya does not voice its opposition to Iran’s brutality at home or its support for terrorism abroad.

Iranian operatives have been caught red-handed in several attempted terror plots in Kenya, and Kenya has made efforts to thwart and detain those responsible. Still, it has seldom pointed a finger at the Islamic Republic. In 2012, two Iranians were found with 33 pounds of RDX explosives. A Kenyan Anti-Terrorism Police Unit official admitted that “the [suspects] have a vast network in the country meant to execute explosive attacks against government installations, public gatherings, and foreign establishments,” but the official fell short of identifying an Iranian intelligence operation. Other reports indicated that Kenyan officials did say the Iranian suspects were members of the IRGC-Quds Force and that the highest levels of the Iranian regime must have authorized the operation. This admission was a notable exception to Kenya’s approach, which centers on charting an independent foreign policy.

Economic Interests: Although Kenya complied with post-JCPOA U.S. sanctions on Iran’s oil sector, it continues to foster cooperation with Iran, where it believes its commercial and technological interests are beneficial. Instead of openly flouting U.S. sanctions, Nairobi engages Iranian companies in niche markets that are not easily sanctioned. Beginning during the latter half of the Rouhani administration and continuing to this day, Iranian companies are looking to access markets for goods classified as humanitarian and exempted from sanctions. According to U.N. data, in 2021, Kenya imported $34 million worth of goods—mostly mineral fuels, oils, and distillation products—from Iran, exploiting a loophole in the U.S.’s energy sanctions to Tehran. Iran continues importing Kenyan tea, Kenya’s number-two hard currency earner.

Ideological Interests: Kenya is ripe for Iranian ideological infiltration, given its population of over half a million Shia. When Ahmadinejad arrived in the capital in 2009, he was greeted by a massive crowd of Muslims chanting “God is great” in Arabic. With a network of cultural and religious centers in Kenya, such as the Islamic Culture and Relations Organization (ICRO), Iran has the institutional cover it needs to deploy elements tasked with radicalizing and recruiting members of the Shia community. These types of institutions tend to be sheltered from sanctions and efforts to close them down because of their seemingly innocuous humanitarian value, which makes them useful tools for the Iranian regime.

Terrorist Activity: The 1998 U.S. embassy suicide truck bombings in Kenya and Tanzania led to an American foreign policy focus on East Africa. Al-Qaeda carried out the bombings, which closely resembled Hezbollah’s bombing of a Marine barracks in Beirut in 1983. A U.S. federal court later concluded that the Islamic Republic and Hezbollah had aided al-Qaeda chief Osama Bin Laden in conducting the attacks. In response to the bombings, President Clinton authorized cruise missile strikes against the terrorist infrastructure in Sudan and Afghanistan. Israel assassinated Abu Muhammad al-Masri, Osama Bin Laden’s deputy and the mastermind behind the Kenya and Tanzania bombings, in Iran in 2020.

Iran has planned and directed several (mostly unsuccessful) terrorist plots in Kenya over the years. In 2012, 33 pounds of RDX explosives were found in Kenya in the possession of two IRGC-Quds Force operatives: Ahmad Abolfathi Mohammad and Sayed Mansour Mousavi. The Iranian nationals admitted to targeting U.S., Israeli, Saudi, and British interests in Kenya and were convicted. Their arrest gave Kenya a pretense to cancel an announced deal from 2009 in which Iran was supposed to ship four million metric tons of crude oil annually to Kenya, but reports indicated that Kenya probably would have made this decision anyway, given international pressure to comply with U.S. sanctions.

In 2015, Kenyan authorities arrested two individuals employed by Iran’s security services to conduct attacks against Western interests. Abubakar Sadiq Louw, 69, and Yassin Sambai Juma, 25, admitted to plotting the attacks in Kenya and allegedly traveled to Tehran on several occasions. Louw was a leader in Kenya’s Shia community. In 2016, Iranian operatives were arrested in Kenya for targeting the Israeli embassy there. In January 2020, days after the U.S. struck and killed Soleimani, al-Shabaab attacked Manda Bay, a U.S. military installation in Kenya, killing 3 U.S. citizens. Again, in 2021, an Iranian national was arrested in Kenya for planning terrorist attacks against Israeli interests. Iranian agents remain active in Kenya, recruiting terrorist cells and plotting attacks against Western interests.

Conclusion: Kenya wishes to preserve its relations with Iran, but the threat of economic costs has disrupted this relationship. Most notably, in 2012, Kenya canceled the announced agreement to import oil from Iran. Therefore, the U.S. Department of the Treasury should target Kenyan individuals and entities seen to be doing business with Tehran to disincentivize new deals and raise the costs of business in the Iranian market. It must pay particularly close attention to trade in goods that have been deemed humanitarian. U.S. diplomacy should also promote cooperative projects between U.S. and Kenya-based companies to support Kenya’s technological advancement in the fields where Iranian companies currently have a foothold.

Morocco

Overview: Morocco is a pro-Western North African country bordering the Atlantic Ocean and Algeria. Iranian-Moroccan relations have declined as Israeli-Moroccan ties have improved. Israel and Morocco are exploring arms deals, intelligence-sharing arrangements, and even a jointly-operated military base. Iran, in turn, has sought to undermine Morocco’s external security through cooperation with Algeria and the Polisario Front and its internal security through ideological infiltration. With the help of its proxy Hezbollah, Iran is attempting to encircle Morocco in pro-Iran sentiment in the hopes that such sentiment will penetrate Morocco itself.

Historical Background: The territorial conflict between Morocco and the Polisario Front refers to Spain’s unilateral withdrawal from Western Sahara in 1975. Morocco won control over the contested area, defeating Algeria’s and Mauritania’s claims to sovereignty. However, the Polisario Front, which controlled some of the territory then, declared the sovereign Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). This led to a protracted conflict that continues to be fueled by Algeria’s support.

In 1979, Morocco received the deposed Shah, causing Iranian Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini to sever diplomatic relations with Rabat and to recognize SADR. In 1991, the Polisario Front was driven back into Algeria’s Tindouf area, and Tehran and Rabat reestablished diplomatic relations. Seven years later, Iran reversed its recognition of SADR. However, these gestures were nominal. Rabat was determined to build close relations with Washington throughout the 1990s, hoping the U.S. would recognize its sovereign claims to Western Sahara. In 2009, Morocco severed diplomatic relations with Tehran in response to the latter’s sectarianism and an Iranian official’s statement that Bahrain was “the fourteenth province” of Iran, a reference to Iran’s historical territorial claim to Bahrain that reaches back to the Persian Empire. Moroccan King Mohammed VI characterized Iran’s efforts to convert Sunnis, which comprise 99 percent of Morocco’s population, as an attack on the monarchy, known for its moderate approach to Sunni Islam.

Notwithstanding these lingering tensions, in 2012, Morocco hedged on the issue of Iran’s nuclear program, referring to sanctions as a last-resort measure that should not impact the Iranian people. Morocco’s acquiescent position warmed relations with Iran. In 2014, Iran promised to respect the Kingdom of Morocco’s sovereignty and the role of King Mohammed VI, effectively lobbying for renewed diplomatic relations on the grounds that it would not use its diplomatic presence in the country to spread Shiism.

In January 2017, Iran and Morocco reestablished diplomatic relations. Later that year, though, Morocco arrested a Hezbollah agent named Kassim Tajideen on an Interpol warrant, leading the group to retaliate against Morocco. After Tajideen’s arrest and subsequent extradition to the U.S., Morocco believes that Iran facilitated Hezbollah’s supply of SAM and Strela missiles to the Polisario Front through its embassy in Algeria. As a result, in 2018, Morocco severed diplomatic relations with Iran, and relations have been on ice since then. In June 2023, Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian voiced his support for better relations with Morocco at a summit in Tehran.

Political Interests: The Iranian regime’s recent charm offensive extends to Morocco but is unlikely to counteract its isolation. Saudi Arabia and Israel have far more diplomatic influence in Morocco than Iran does. Morocco joined the Saudi-led international coalition formed in 2015 to restore the internationally-recognized government of President Hadi in Yemen. In 2016, King Mohammed VI attended a Moroccan-Gulf summit to improve ties with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). In 2018, Morocco’s relations with Saudi Arabia, while tense given Morocco’s neutrality on the conflict between Qatar and the other Gulf States, improved after Morocco severed relations with the Islamic Republic. In 2022, the Arab League endorsed a Saudi-led resolution calling for solidarity with Morocco vis-à-vis Iran.

After Morocco severed relations with the Islamic Republic, Moroccan-U.S. relations also improved. Morocco’s distance from Tehran fit into the U.S.’s isolation strategy, which went into full effect after the Trump administration withdrew from the JCPOA in 2018. The Trump administration’s ultimate decision to recognize Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara facilitated Morocco’s agreement to normalize ties with Israel under the Abraham Accords in December 2020. In November 2021, Israeli Defense Minister Benny Gantz signed a defense MOU with his Moroccan counterpart in Rabat. The MOU would facilitate intelligence sharing, research, and joint military training. Although specific weapons deals were not reported then, Rabat has expressed interest in buying Israel’s Iron Dome air defense systems. Moreover, Israel may be looking to establish a military base in Morocco.

Ideological Interests: In 2008, Morocco uncovered two Shia clerical networks. In 2018, reports emerged on Hezbollah’s infiltration of educational systems in the Ivory Coast through Lebanese investments to fund schools there. While details on the schools remain scarce, they were reported to be set up as part of a joint effort on behalf of Hezbollah and the Lebanese investors, suggesting that the schools’ leadership likely had ties to Hezbollah and that radical Shia Islam, anti-Americanism, and antisemitism influenced their curriculums. Allegedly, the investors concurrently launched a lobbying campaign to undermine Morocco’s agenda, which is centered on moderate Sunni religious influence. In response, Morocco established its schools to protect the Moroccan diaspora from Iranian ideological and religious influence. In 2022, Moroccan Foreign Minister Nasser Bourita accused Tehran of spreading radical Shiism on the African continent.

Conclusion: Tehran views Morocco as an adversary, given the latter’s relations with Saudi Arabia and Israel, and Morocco perceives Tehran’s support for militant Shiism, the Polisario Front, and Algeria as a threat to its regime. Iran’s efforts to destabilize Morocco may accelerate as Tehran tries to impose costs for Rabat’s participation in the Abraham Accords. The U.S. should, therefore, consider maintaining its recognition of Morocco’s claim over Western Sahara as a means of ensuring Rabat’s continued adoption of a pro-Western and pro-Israeli foreign policy. This will undermine Iran’s diplomatic offensive and Hezbollah’s ideological infiltration and promote further security cooperation to deter Iran.

Niger

Nigerien Foreign Minister Ibrahim Yacouba and Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif in Tehran in 2016 (Source: Iran Front Page)

Nigerien Foreign Minister Ibrahim Yacouba and Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif in Tehran in 2016 (Source: Iran Front Page)

Overview: Located in West Africa, Niger is one of Africa’s poorest countries despite its abundant natural resource wealth. This landlocked nation has large deposits of uranium, coal, and gold, which make up a large share of its economic activity. Since its independence from France in 1960, Niger has experienced several successful coups and dozens of aborted coup attempts. Its most recent coup in July 2023 pitted the West against a newly installed military regime led by a previously low-profile general, Abdourahmane Tchiani. The military leadership mobilized behind him and recognized the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland as the legitimate government of Niger, with Tchiani as its head, until elections could be held in three years. Iran’s position on the military coup—at first marked by silence, then by implicit recognition of the new government—has been calibrated to preserve its interests in West Africa while not foreclosing potential cooperation with the Nigerien junta.

Historical Background: When Ahmadinejad visited Niger in April 2013, Western analysts speculated that he was seeking to procure Nigerien uranium, given Iran’s aggressive extraction of its deposits. The trip occurred weeks after Iran announced the inauguration of two uranium mines and a milling plant. Ahmadinejad claimed the Iranian mines were sufficient for Iran’s uranium needs. Niger’s foreign minister said that Niger’s sale of uranium was not on the agenda and that any such arrangement would have to be compliant with international laws and regulations. No uranium deals were reported.

Rouhani’s foreign minister, Javad Zarif, went to Niger in October 2017 and May 2019 to bolster bilateral economic ties. Details on the outcomes of these talks were scarce. Still, Iranian media reported that Zarif also met with President Mahamadou Issoufou to discuss broader regional and international topics and how to boost trade. It was unclear if any significant agreements were reached at this time.

In September 2020, before the UN arms embargo was set to expire against Iran, the U.S. invoked the “snap back” mechanism to restore all UN sanctions against Iran. The other JCPOA signatories (France, the U.K., Germany, China, and Russia) rejected Washington’s initiative. President Rouhani reached out to Niger, which had assumed the UN Security Council’s rotating presidency, to request that it stand against the U.S. initiative, and Niger took the same position as the other JCPOA signatories.

Mohamed Bazoum’s election to the presidency in April 2021 marked Niger’s first post-independence peaceful transfer of power. However, the military overthrew his government in July 2023 and detained him. General Tchiani’s seizure of power called into question the continuity of U.S. and French support to the Nigerien government’s counterterrorism program.

The Nigerien coup was particularly damaging to France’s counterterrorism interests in the region in the context of recent coups in Mali and Burkina Faso—both of which resulted in France’s military expulsion. France receives 15 percent of its uranium from Niger, its former colony. Tchiani called on the foreign powers that had partnered with the previous government, namely the U.S. and France, to recognize his claim to power and continue to support Niger’s counterterrorism efforts. He may not be expected to take the country in a hardline anti-Western direction, as was the case in Mali and Burkina Faso after their coups, but continuing the U.S. and France-backed counterterrorism efforts in Niger depends in part on the U.S. and France’s openness towards recognizing the military junta.

After the military takeover, the U.S. declared it a coup, demanded the restoration of civilian rule, and signaled its readiness to impose costs on the military leadership, as did France. The New York Times noted that due to the U.S. labeling the event as a coup, it could no longer provide counterterrorism assistance to the Nigerian government. As a result, troops stationed at U.S. Air Base 201 in Niger, a $100 million base, are idle. The base has been described as the most important U.S. military asset in a region fast-becoming more vulnerable to terrorist activities and groups. Other Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) regional powers released more neutral statements than the U.S. and European countries.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), a regional political and economic bloc, threatened to intervene militarily if Bazoum was not restored and immediately suspended the bloc’s commercial activity with Niger and froze its state assets. Mali and Burkina Faso—former members of ECOWAS that had their memberships suspended because of military coups in their countries—said that such an intervention by ECOWAS could trigger their military involvement in defense of Tchiani. The U.S. joined Europe and ECOWAS, imposing crippling sanctions and pausing its economic assistance program, which was valued at $200 million per year. In October 2023, France began withdrawing its troops from Niger after weeks of pressure from the junta.

Political Interests: Publicly, the Raisi administration has taken a cautious, if not neutral, position on the military coup. In October 2023, President Raisi said his government was ready to cooperate economically with Tchiani’s government. However, if Iran calculates its economic relations in the region are at stake, it will limit its cooperation with the new government. For instance, Iran may not wish to damage relations with Nigeria, an African trading partner with Iran and a member of ECOWAS who would likely respond negatively if Iran pursued relations with Niger’s current leadership.

As Niger’s relations with the West and ECOWAS deteriorate, Iran will likely try to draw the isolated group of coup leaders in the Sahel into its orbit. Niger’s isolation could also disrupt its ability to form relations with Israel, which benefits Tehran. In 2021, Israeli Minister of Intelligence Eli Cohen said that Israel and Niger engaged in secret talks regarding normalization. However, as with the October 2021 military coup in Sudan, the coup in Niger could make it more difficult to build closer relations. Tchiani's seizure of power from a democratically-elected government makes him unwelcome in Western capitals.

Saudi Arabia’s interests are also at stake. In 2017, Saudi Arabia and Niger signed three bilateral agreements, agreeing to a security arrangement, the Kandadji Dam project, and rural development projects. These projects and Saudi Arabia’s construction of local primary schools in Niger were likely conditioned on Niger’s cooperation on regional matters involving Iran. Saudi Arabia unequivocally condemned the military takeover, which seems to suggest that the Saudi deals could be in jeopardy.

Terrorist Activity: Tchiani will need external partners to ensure his regime’s security and combat Islamic extremist organizations in its territory, leading some analysts to believe he could reach out to Russia or Iran. The Wagner Group, a Russian private security contractor known for meddling in the political affairs of African countries, has long sought inroads in the Sahel to counter the West, which the coups in this area have provided. Tchiani’s need for a new counterterrorism partner in lieu of Western support could make Tehran appealing, but such an arrangement constitutes a risk for Tchiani, given that the IRGC-Quds Force is itself the special operations wing of a U.S.-designated terrorist organization. If and when the Quds Force deploys to the region, it will import its terrorist enterprise, which would imperil the weak state and further undermine security in the volatile Sahel region.

Conclusion: The U.S.’s punitive actions against Tchiani risk pushing him closer to Tehran, but American acceptance of Tchiani will come as a challenge in the context of its human rights priorities. The Tchiani regime will likely impede fundamental political and economic freedoms, which the U.S. prioritizes as a foreign policy matter. Suppose the U.S. decides to sanction the military regime to show its commitment to human rights and curtails or discontinues its counterterrorism support to the junta. In that case, the U.S. must find ways to conduct counterterrorism operations covertly in the country—even without the central government's approval.

Nigeria

Sheikh Ibrahim Zakzaky with a photo of Supreme Leader Khamenei (Source: BBC)

Sheikh Ibrahim Zakzaky with a photo of Supreme Leader Khamenei (Source: BBC)

Overview: In West Africa, Nigeria is Africa’s most populous country, largest economy, and biggest oil producer. In 2022, Nigeria’s gross domestic product (GDP) of $477 billion beat out that of Egypt ($475 billion) and South Africa ($405 billion). As such, it is Iran’s third-largest trading partner on the continent after South Africa and Kenya. Nigeria is also an ideological battleground, given its religiously diverse demographic composition. According to the Pew Research Center, Muslims and Christians make up a near-even split within a population of 216 million. However, Muslims make up the majority and are concentrated in the north of the country.

While pursuing formal diplomatic initiatives in Nigeria, Iran also seeks ties with non-state actors that threaten state security, namely the Shia Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN), which Nigeria banned in July 2019. A Nigerian court granted the government permission to designate the group as a terrorist organization, but the government has not. Iran has continued to cultivate influence among Nigeria’s Shia population, with the IRGC leading efforts to empower the IMN financially, ideologically, and materially.

Historical Background: Iran and Nigeria maintained diplomatic relations, established around 1976, following the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The Revolution did not lead to a rupture but dramatically altered Iran’s interests in the country. Under Supreme Leader Khomeini, the Islamic Republic swore to export its system of government and the radical beliefs and traditions upon which it is based, causing fear among the leaders of the Sunni Muslim world, including Sunni heads of state. These fears were not only felt across the Middle East but also in Africa.

Shia Islam took root in Nigeria after the Islamic Republic entered what the CIA referred to as its “activist phase” on the continent. Following Iran’s attempted counteroffensive into Iraq in the spring of 1982, Iran went on a diplomatic and ideological offensive in Africa. Iran recruited and engaged a previously obscure Nigerian Islamic preacher, Ibrahim Zakzaky. His outspoken hatred of secularism and his advocacy for an Islamic state attracted Iran’s attention. However, it wasn’t until 1996 that he converted to Shiism, leading many followers to convert with him (other accounts assert he converted in 1979). After his conversion, he and his followers formed the IMN.

Iranian-Nigerian relations gained traction after Olusegun Obasanjo was elected to the presidency in 1999, promising to improve the economy, stabilize the political system, and form relations with foreign powers. In 2000, reports suggested that Nigeria and Iran sided with each other in disputes within OPEC over oil production levels (both have a history of cheating on their quotas to take advantage of high oil prices, pitting them against Venezuela and Saudi Arabia). The following year, President Obasanjo traveled to Tehran and met President Khatami to discuss their respective oil and agriculture industries. Khatami said the two leaders considered “cooperation and coordination in the field of oil,” seemingly affirming the countries’ shared OPEC agenda. Obasanjo also met Supreme Leader Khamenei and condemned Israel for its treatment of the Palestinians. In 2005, Khatami signed several bilateral agreements in Nigeria over power generation and industry.

When Ahmadinejad was elected later in 2005, Iran became more isolated and viewed Nigeria as a higher priority. In 2010, Nigeria assumed the UN Security Council’s rotating presidency, increasing Tehran’s interest in a diplomatic partnership. Iran sent Ahmadinejad on a state visit, but Nigeria nevertheless voted in support of a UN Security Council resolution against Iran. On his trip, Ahmadinejad advocated for cooperation in power generation, going so far as to suggest that Iran would help Nigeria develop its nuclear program if it so desired. Nigeria turned the proposal down due to U.S. pressure and domestic opposition.

During the Rouhani administration in the mid-2010s, tensions between the Nigerian state and the IMN influenced Iranian-Nigerian relations. In 2014, Zakzaky, then leader of the IMN, accused the Nigerian military of killing three of his sons and 30 of his supporters at an IMN-organized anti-Israel rally. Then, in 2015, Nigerian forces killed over 300 IMN members after they blockaded a convoy led by Nigerian Army Chief of Staff Lieutenant General Tukur Buratai, allegedly seeking to assassinate him. The army reportedly opened fire on the protesters after a projectile thrown at the general’s vehicle was mistaken for gunfire. Subsequently, the army firebombed the IMN’s religious center and sent troops and tanks to Zakzaky’s home to arrest him.

This brutality sparked fears that state security forces would inadvertently radicalize the group, as observers argue Boko Haram was radicalized after the extrajudicial killings of its leader and other suspected members in 2009. Zakzaky was arrested and detained without charge. In 2016, he was charged with conspiracy to kill Buratai. Iran’s then-Deputy Foreign Minister for Arab and African Affairs, Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, held the Nigerian government responsible for the deaths of the IMN members but maintained that bilateral relations were stable. Rouhani called for an investigation into Zakzaky’s imprisonment and the army’s use of force against the protesters.

According to Iranian state-linked media, in June 2022, Iran’s minister of industry, mines, and trade, Reza Fatemi Amin, and Nigeria’s minister of state for foreign affairs, Zubairu Dada, signed nine MOUs in Tehran to boost economic and trade ties. During Dada’s trip to Tehran, Abdollahian invited Nigeria’s president to Iran. In August 2022, the two countries’ oil ministers agreed to an MOU on energy in which Nigeria would receive Iranian engineering assistance in its oil fields and refineries. In 2023, however, Nigeria’s Central Bank issued a statement urging banks and financial institutions to increase monitoring of transactions with Tehran, given the high risk of money laundering.

Political Interests: Nigeria is considered a member of the anti-Iran bloc at the African Union (AU). Nevertheless, it has maintained uninterrupted diplomatic relations with Iran since 1976. Successive Iranian administrations have kept a heavy diplomatic presence in Nigeria. At the same time, Iran’s overt support for the IMN—a security threat in the eyes of the Nigerian state—strains bilateral relations and diminishes the Iranian embassy’s ability to elicit support for its positions. This duality is a sign of discord within Iran’s foreign policy bureaucracy, which the IRGC dominates. If security in Nigeria deteriorates because of the IMN’s activities, Iranian-Nigerian relations likewise will deteriorate. Under those circumstances, Nigeria would likely take a more active role in the AU in speaking out against Iran.

Ideological Interests: Iran’s ideological interests in Nigeria date back to the early 1980s, when the CIA identified Nigeria as one of the countries in which Iran sought to recruit students for religious courses in Iran. Though Sunni at the time, Zakzaky was one of the first African Islamic leaders to receive an invite from the Islamic Republic. After returning to Nigeria, he combined Khomeini’s symbolism and rhetoric with the Sunni Muslim Brotherhood’s ideology, thereby appearing to stay true to his roots as a leader of the Nigerian Muslim Brotherhood. Zakzaky was a follower of Sayyid Qutb, the Muslim Brotherhood’s thought leader. At first, Zakzaky retained his radical Sunni beliefs, which called for Islamic governance, but his inspiration quickly shifted in 1979 to the successful Islamic Revolution and Khomeini’s ideological system, known as velayat-e faqih, which also calls for Islamic governance.

The number of Shiites in Nigeria has grown steadily since the early 1980s as a result of the radical cleric’s sectarian and political campaign to establish an Islamic theocracy in Nigeria. A majority of Nigeria’s 100 million Muslims are Sunni, but the Shia population totals four million people. Although not all Nigerian Shia belong to the IMN, they are a target demographic for the Iranian regime. Iran finances the IMN’s propaganda, social services, schools, and mosques—not unlike its engagement with Hezbollah—and provides critical ideological support. In October 2023, Zakzaky traveled to Tehran and met with Supreme Leader Khamenei, indicating the current supreme leader’s intention to continue to spread his influence in Nigeria.

Terrorist Activity: The IMN’s leadership is committed to the Islamic Republic’s ideological principles. However, the group seems to differ from other Iran-backed proxies and partners in that it does not openly espouse violence as a means of achieving its political aims. The Combatting Terrorism Center (CTC) at West Point published an analysis in 2013 that claimed the group does not promote violence while acknowledging that IMN members occasionally turn to more radical groups. The American Enterprise Institute found that converting to Shiism may be a way to distinguish one’s identity from mainstream Sunni elites, who tend to favor a pro-Western view of the world; and Nigerian Christians, who are more skeptical than Muslims about Iran’s nuclear program. At the same time, Iran expert Matthew Levitt at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy published a report in 2016 citing a former Iranian foreign ministry advisor who said that Iran had trained the IMN to assemble explosives.

The IRGC and Hezbollah have been caught on several occasions plotting attacks against Western and Israeli interests in Nigeria. In 2010, an IRGC operative and three Nigerians were charged in a Nigerian court for attempting to transfer mortar rounds and 107 mm Katyusha rockets through Nigeria’s Port of Lagos, intended for the Gambia. In 2012, the U.S. Department of the Treasury tied IRGC-Quds Force Commander Esmail Qaani to the intercepted shipment of 240 tons of arms, which were loaded into 13 shipping containers at the Iranian port of Bandar Abbas. As previously noted, Qaani was deputy commander in the Quds Force in charge of the Africa portfolio at the time of this operation.

Azim Adhajani, the individual accused of conducting the operation, was identified as a Tehran-based businessman and denied working for the IRGC, presumably to preserve the regime’s plausible deniability. However, the UN had already blacklisted him as an IRGC operative.

In 2013, Nigerian security services arrested Mallam Abdullahi Mustaphah Berende on charges that he headed an Iran-backed terrorist cell tasked with assassinating Nigerian officials, including the president, and plotting attacks against Western and Israeli interests. He confessed to studying Shia teachings in Iran and being recruited to surveil targets in Lagos, where his handlers believed an Israeli intelligence facility was located. In a separate incident later that year, three suspected Hezbollah operatives of Lebanese descent were arrested in a raid that uncovered anti-tank rounds and landmines, 122 mm artillery rounds, rocket-propelled grenades (RPG), and AK-47 rifles and ammunition.

Conclusion: Iran will continue to enflame sectarian tensions in Nigeria (as it does in the Middle East) as long as violence against the Shia minority fuels the Islamic Republic’s propaganda. The U.S. should, therefore, consider facilitating inter-faith dialogue in Nigeria to lower the sectarian tension. The U.S. has an interest in convening faith leaders from different sects of Islam and Christianity to promote tolerance and moderation, which would directly counter Tehran’s radicalism. However, ties between Hezbollah, the IRGC, and the IMN need to be carefully probed. Although the IMN has not always openly espoused violence, the group’s terrorist capabilities should be kept in check by working with the Nigerian government to prevent Iranian infiltration and the proliferation of arms.

Somalia

Overview: Strategically located in the Gulf of Aden, Somalia is a critical transit hub for weapons. The East African country has a long history of weak central governance that fails to contain the violence that affects large swathes of its territory. Thus, Somalia is a fertile ground for insurgent groups, terrorist organizations, and foreign meddling. In the mid-2000s, for example, Iran armed and equipped an Islamic insurgency in Somalia that opposed the transitional government. The group, known as the Union of Islamic Courts (UIC), splintered into the al-Qaeda affiliate al-Shabaab, which remains active in the country today and continues to receive Iranian material, financial, and logistical support.

Historical Background: Mohamed Siad Barre ruled Somalia from 1969 to 1991. After taking power in a coup, he remade Somalia into a one-party communist state with the Soviet Union’s backing. The Barre regime coopted the communist ideology and called for national unity among the clans to neutralize the clans threat to his rule. Somalia’s neighbor, Ethiopia, had already experienced a communist revolution in 1974, which overthrew Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie. The Shah perceived the two communist states as a dual threat to Iran’s security interests in the Horn of Africa.

In 1977, the Soviet-backed regime in Somalia invaded a disputed border region with Ethiopia, triggering the year-long Ogaden War. Disapproving of the invasion, the Soviet Union withdrew its support for Barre and rushed support to Ethiopian dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam. The Shah, seeing an opportunity to partner with Barre after the latter’s break with the Soviet Union, backed Somalia’s war against Ethiopia to counter further Soviet penetration. That year, the Carter administration likewise offered its first military assistance to Somalia to supplant Soviet influence. However, Somalia lost the unpopular Ogaden War despite the backing of the U.S., Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Sudan. Then, it allied with the U.S. for the duration of the Cold War.

After the war, Barre turned to the clans to sustain his rule, parting ways with his former communist ideology and instituting a bloody crackdown on all internal political opponents, including those backed by Ethiopia’s military junta, the Derg. At the same time, Barre’s regime continued receiving U.S. military assistance. Throughout the 1980s, the Derg backed various insurgencies in Somalia instead of the Barre government. However, Barre remained in power until 1991, largely because of his relations with local armed clans, whom he played off against each other. In particular, his government funded and armed paramilitaries picked from subdivisions within the clans in exchange for their loyalty, which weakened the clans.

In 1985, U.S. military aid to Somalia approached $33 million in order to counter the Soviet Union. Barre’s son-in-law, also known as the “butcher,” led Somalia’s state forces in the late 1980s in a brutal repression campaign targeting the main opposition group, the Somali National Movement. By the late 1980s, the military began to disintegrate along clan-based lines, leading to Barre’s growing reliance on his own clan and eventual demise.

During this period, Somalia and the Islamic Republic did not maintain the friendly terms that characterized relations under the Shah. The rupture was due to Somalia’s Western orientation and the newly established Islamic Republic's inward focus on consolidating its power amid the post-revolutionary tumult. However, Barre’s dependence on and favoritism towards his own clan brought about infighting within the military and finally led to the overthrow of the Barre government by clan-based armed opposition groups in 1991, resulting in a power vacuum and civil war that continues to this day.

Iran’s direct involvement in the Somali civil war dates back to 2006, when it began transferring weapons and ammunition to the Islamist UIC—allegedly in exchange for access to Somali uranium—in violation of a 1992 UN arms embargo against Somalia. By 2006, the UIC had seized large swathes of the country’s south, where uranium mines and the capital, Mogadishu, are located, triggering the Ethiopian National Defense Forces to intervene and stand up a pro-Western government. However, although Ethiopia had U.S. support and quickly routed the UIC in December of that year, a more resilient and extreme terrorist organization splintered off and continued receiving Iranian arms. In exchange for Iran’s support, al-Shabaab dispatched fighters to aid Hezbollah in its 2006 war against Israel.

An international coalition mobilized behind the Ethiopian-backed Transitional Federal Government (TFG) in Somalia. The UN approved the deployment of a regional intervention force to arm and train the TFG’s security forces. In 2007, it allowed weapons transfers to the Somali state to enable it to build a security sector and combat terrorist organizations on its soil. In 2009, Ethiopia withdrew its forces, claiming victory over the rebels, and the U.S. began supplying arms to Somalia. In June of that year, the U.S. provisioned 40 tons of small arms and ammunition. Still, al-Shabaab was able to launch a violent insurgency and subsequently gain control over the majority of the country.

Later, in 2009, al-Shabaab claimed responsibility for a suicide bombing that killed three government ministers and 16 others at a ceremony in Mogadishu. After this incident, Iran appeared to withdraw its support for insurgent groups, at least publicly. Iran recognized the government of Somalia and called for a peaceful diplomatic process to end the conflict. However, Somalia’s relations with Tehran never improved, especially given that Somalia had positive relations with the U.S., which backed the Ethiopian military operations that overthrew the former government and installed the TFG. Furthermore, the U.S. had become heavily involved in Somalia’s counterterrorism program. Not only has the U.S. provided weapons to Somalia, but it has carried out dozens of air strikes against al-Shabaab and other terrorist targets in Somalia since the late 2000s, with the cooperation and approval of Somalia’s government.

U.S.-Somalia relations improved in 2012, when the latter held parliamentary and presidential elections and then adopted a provisional constitution, leading the U.S. to formally recognize the federal government of Somalia in January 2013. The UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon then called for an end to the 1992 UN arms embargo because Somalia needed arms to consolidate its gains against terrorist groups—a position that the U.S. at the time also adopted against critics who argued that the security sector had close links to the warlords and clan-based militias.

Somalia’s decision to close down Iranian religious centers in 2014 gave further indication that Somalia had little to no interest in developing relations with Iran, preferring relations with the U.S. and Western-aligned states. Two years later, Somalia, Sudan, and Djibouti severed diplomatic relations with Iran following an attack on the Saudi embassy in Tehran.

Terrorist Activity: Throughout the civil war that followed the fall of the Barre government, Somalia remained a “failed state” from which al-Qaeda, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), and ISIS affiliates operated. According to the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), ISIS has its own branch in Somalia that conducts assassinations and improvised explosive device (IED) attacks in the pursuit of an African Islamic caliphate. The Sunni extremist group represents a security threat to the Islamic Republic. It has been held responsible for and claimed several terrorist attacks in Iran, including a January 3 suicide bombing attack in Kerman, Iran, that took over 80 lives. However, the same cannot be said about al-Qaeda and its Somali affiliate, al-Shabaab. Iran provides al-Qaeda with a safe harbor for its leadership and has coopted al-Shabaab, which splintered from the UIC, its former insurgent partner.

External actors have sought to capitalize on the chaos and instability of civil war by taking sides with subversive force. For example, in the mid-2000s, Eritrea supported Islamist militias, including al-Shabaab, in Somalia against the Ethiopian-backed government. At this time, Iran began supporting the UIC and then al-Shabaab. In 2008, Iran sent IRGC-Quds Force specialists to advise Eritrea on the war in Somalia, as noted in the above report on Eritrea.

After Eritrea restored relations with Somalia in 2018 as a result of the UAE-brokered accord between Eritrea and Ethiopia, Eritrea pledged to end its support for the militias, but al-Shabaab continued to receive Iranian material, financial, and logistical support in Somalia. In 2017, Somalia’s minister of foreign affairs alleged that al-Shabaab had seized uranium mines and intended to extract uranium for Iran in exchange for Tehran’s ongoing support. In 2018, the Associated Press reported that embargoed charcoal exports from Somalia were flowing to Iran, earning al-Shabaab millions of dollars in annual revenue.

According to Somali officials, Al-Shabaab’s terrorist capabilities have grown significantly since 2017 as a result of foreign-supplied arms. In 2019 and 2020, al-Shabaab attacked U.S. military bases in Somalia and Kenya and a European Union military convoy in Mogadishu. The deadly January 5, 2020, al-Shabaab attack against a U.S. base in Kenya was notable because it occurred two days after the U.S. assassinated IRGC-Quds Force Commander Qassem Soleimani in Iraq. Iran has allegedly offered bounties to al-Shabaab to attack U.S. forces in Somalia and the region.

Arms have also flowed out of Somalia towards Yemen and from Yemen towards Somalia. In 2013, the UN Security Council found that Iran and the Houthis armed Islamist militants in the south of Somalia—accusations which Tehran denied. In 2017, the IRGC shipped weapons to the Houthis via Somalia to utilize sea lanes that are less closely monitored by Western naval assets. The Houthis moved Iranian-origin arms, including AK-47 rifles, RPGs, and ammunition, from Yemen to Somalia via the semi-autonomous Puntland in northern Somalia. Somalia is also a gateway to Africa’s lucrative arms market, which has extended from Somalia into Kenya, Ethiopia, South Sudan, Mozambique, and Tanzania.

Conclusion: Iran resorted to subversive activities in Somalia to thwart Western counterterrorism objectives in the Horn of Africa. Adopting the same playbook it uses in the Middle East, Iran believes U.S. interests are vulnerable to attacks on the African continent. Despite religious differences, Tehran has coopted violent Sunni extremist organizations like al-Shabaab based on their shared hatred of the U.S. The U.S. should, therefore, consider building up the naval interdiction capabilities of the Somali Navy and bolstering the Somali government’s counterterrorism operations.

South Africa

South African President Nelson Mandela and Supreme Leader Khamenei in Iran in 1992 (Source: Iran Project)

South African President Nelson Mandela and Supreme Leader Khamenei in Iran in 1992 (Source: Iran Project)