Iran’s War on Workers and the Middle Class

Download PDFPage Navigation

Iranian workers are victimized by the regime in Tehran and have few legal rights or protections. Those who support the fundamental rights of workers—to assemble freely, protest unfair labor conditions, collectively bargain, receive fair contracts, and form independent unions—must oppose the Iranian regime’s abuses.

On the first May Day after Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the Islamic Republic’s founder, proclaimed, “Dedicating [only] one day to the labourer, is as though we dedicate [only] one day to the light, [or only] one day to the sun.” In practice, however, the regime tramples the rights of workers and responds with repression to their demands for independent unions, fair wages, timely payment, and safe working conditions.

According to the U.S. Department of State’s 2021 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, Iranian authorities still “[do] not respect freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining”; have “severely restricted freedom of association and interfered in worker attempts to organize”; ban “strikes… in all sectors”; treat “labor activism … as a national security offense” punishable, in some cases, by the death penalty; and “harassed trade union leaders, labor rights activists, and journalists during crackdowns on widespread protests.”

Labor Unions

The Islamic Republic’s Labor Code does not grant citizens the right to form independent unions, violating Iran’s commitments as a ratifier of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and a member of the International Labor Organization. Iran has not ratified three ILO core conventions that guarantee freedom of association, the right to organize and collectively bargain, and the minimum worker age. However, the ILO’s Declaration of Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work states, “All members, even if they have not ratified the Conventions in question, have an obligation arising from the very fact of membership in the Organization, to respect, to promote, and to realize these core conventions.”

Iran is also a party to the UN’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which guarantees freedom of association. The Iranian constitution also guarantees freedom of association and assembly (in articles 26 and 27), putting Iran’s labor policies at odds with its own laws. The “Islamic labor councils” approved by the Labor Code are chiefly ideological and do not function as defenders of workers’ rights. They fall under the jurisdiction of the Worker’s House, a state-sponsored labor organization beholden to the government. According to the State Department, Iran’s labor councils “consist[ing] of representatives of workers and a representative of management, [are] essentially management-run unions that undermined workers’ efforts to maintain independent unions.”

Persecution

Amnesty International notes that many trade unionists face lengthy prison sentences on concocted national security charges, undergo torture and ill treatment in detention, and face continued harassment and violence from security forces and dismissal from their jobs, even after release.

Iran continues to imprison or unjustly detain, torture, convict, imprison, and even sentence to death trade unionists for their peaceful activism and efforts to organize workers. Amnesty International reports many trade workers face continued harassment and violence from security forces and dismissal from their jobs, even after release. The International Trade Union Confederation places Iran in its worst category (“no guarantee of rights”) for non-failed states when it comes to upholding the rights of trade unionists.

The regime frequently suppresses peaceful annual demonstrations on International Workers’ Day (May 1). On that day in 2021—according to the State Department, which cited media and NGO reports—“Police attacked and arrested at least 30 activists who had gathered for peaceful demonstrations demanding workers’ rights in Tehran and elsewhere. All detainees were later released on bail.” On May 1, 2019, the police attacked and jailed 25 Iranians, 35 Iranians peacefully protesting by the parliament. The 35 included labour rights activists Atefeh Rangiz and Neda Naji, “who were sentenced, respectively, to five years and five and a half years in prison for participating in the protest,” according to Amnesty International.

One case of the regime’s oppression of trade union leaders is that of Jafar Azimzadeh, head of the Free Union of Iranian Workers. He served a six-year prison sentence for organizing a widely-signed petition to increase Iran’s minimum wage—including 13 months tacked on for “propaganda against the regime” after he had already been released. He reportedly became infected with COVID-19 behind bars—a common experience in Iran’s notoriously overcrowded, unsanitary prisons—and the authorities refused to provide him with medical care. In response, he and 11 of his fellow inmates went on a three-week hunger strike. He was released again in April 2021.

Hostage Taking

Another persecuted labor rights activist is British-Iranian dual national Mehran Raoof, whom the regime holds hostage. In October 2020, IRGC intelligence functionaries raided and searched Raoof’s home and arrested him, confiscating his computer and several other belongings. The Iranian regime arrested other labor rights activists throughout the country that month.

A colleague of Raoof who lives in London told the Daily Telegraph that Raoof helped translate news articles from English to Farsi. He added that the Iranian government had detained Raoof and 15 other workers because a young girl had surreptitiously recorded their conversations about labor rights at a coffee shop.

The authorities threw Raoof into Iran’s notoriously brutal Evin Prison. He has been in solitary confinement for months, and the authorities have refused to let him contact his immediate family—none of whom live in Iran—or meet with the judiciary-certified Iranian attorneys whom his family hired to represent him. His friends have attempted to hire another attorney of Raoof’s choice, but the government has refused to make Raoof’s case file available to that lawyer before Raoof’s trial.

The regime has never publicly stated the precise charges against Raoof and the status of his case. His trial date was set for April 28, 2021, but little or no news from his trial was reported publicly. Raoof was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment by Branch 26 of Tehran’s Islamic Revolutionary Court, according to an August 4, 2021, tweet by his lawyer. The attorney, Mostafa Nili, said that Raoof was sentenced to ten years for the crime of “participating in the management of an illegal group” and eight months “for propaganda activities against the regime.”

Truck Drivers

Truck drivers have served as the engine of the revived Iranian protest movement due to their prominent role and their demonstrated capacity to organize and plan effective strikes and demonstrations. Truck drivers, particularly oil transporters, can cripple Iran’s economy through prolonged work stoppages. However, the regime has responded to their protests over low wages and high maintenance costs with threats, intimidation, arrests, and violence.

Truck drivers in dozens of Iranian cities have participated in a series of strikes and demonstrations in recent years to bring attention to their grievances, including low wages and the rising cost of gas, parts, and supplies. Iranian authorities arrested hundreds of truck drivers, including at least 261 drivers in 19 provinces, following a round of protests in September and October 2018. Iranian officials called for harsh penalties for striking truck drivers, and Iran’s prosecutor-general went as far as issuing a public statement calling for the death penalty for the initiators of the protests.

Teachers

In recent years, teachers’ associations have become a central target for government repression. Police have initiated crackdowns on teachers who have been found to belong to these associations; have publicly celebrated International Workers’ Day, World Teachers’ Day, or National Teachers’ Day; and/or have been involved in protests. The regime blocked teachers from celebrating International Workers’ Day and Teachers’ Day and “continued to arrest and harass teachers’ rights activists from the Teachers Association of Iran and related unions,” according to the State Department.

Two prominent leaders of the Teachers Association, Mahmoud Beheshti-Langroudi, and Esmail Abdi, remain incarcerated in Tehran’s infamously brutal Evin Prison on national security charges for their past peaceful activism. Abdi received a medical furlough in March 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, which was rampant in Iranian prisons. However, the authorities ordered Abdi back to prison one month later to serve a suspended sentence of 10 years that he had been given in 2010 for “gathering information with the intention to disrupt national security” and “propaganda against the state.” Abdi came down with COVID after going back to Evin.

Another teacher activist, Hashem Khastar, was sentenced to 16 years imprisonment in March 2021. Khastar was arrested in 2019 after adding his name to an open letter calling for the supreme leader to step down.

Hostage Taking

The regime also used hostage-taking to crack down on teachers-union activity. In May 2022, the authorities arrested Cécile Kohler, a French national and educator who heads the National Federation of Education, Culture and Vocational Training (FNEC FP-FO), reportedly the largest federation of teachers’ unions in France. Jacques Paris, her partner, was also arrested.

Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security said on May 11, 2022, that it had arrested two Europeans for “promoting unrest and instigating chaos,” in the words of the Iran International news service. The ministry claimed the two had entered Iran in order to exploit ongoing protests to undermine Iranian society and had met with the Coordination Council of Iranian Teachers’ Trade Associations, which has organized numerous demonstrations.

Iranian state television broadcast more particulars on May 17, identifying both Kohler and Paris by name and claiming “the two spies intended to foment unrest in Iran by organizing trade union protests.” The broadcast said the two “took part in anti-government protests and met members of the so-called Teachers' Association,” displaying footage of the detainees meeting with demonstrating Iranian teachers and participating in demonstrations. A recording of the arrest was also shown.

Oil Workers

Strikes by thousands of oil and petrochemical workers in Iran began in June 2021, protesting low wages, exploitative contracts, and poor living conditions. The organized strikes are referred to as Campaign 1400, corresponding to the contemporary Iranian calendar year. The strikers were mostly employed on temporary contracts by private subcontractors for Iran’s oil ministry.

The regime-owned National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) has increasingly relied on subcontractors during the last 20 years. The subcontractors largely hire workers on temporary, rolling contracts that pay a fraction of what employees at NIOC and other state-owned companies make.

According to Middle East Eye, “the minimum wage for contract workers is around 25 million rials ($100) a month and their maximum salary is a little over 40 million rials ($160),” well below the cost of living. One striker said, “Our salaries are less than half of the permanent oil workers, employed officially by the oil ministry, and we are denied many benefits of official staff, including access to the oil ministry's hospital facilities. We are oppressed by the subcontractors and are deprived of the bonuses of the permanent workforce of the oil ministry. This is while we have the same expertise and experience of the permanent workers.”

And many contract workers work seven days a week for the duration of their rolling, temporary contracts. “I currently work 25 days a month,” another striker stated, “and I have only five days off, while commuting itself destroys two days, leaving me only three days to live along with my beloved family. While I sometimes work more than permanent workers who get 480 million rials [$1,920] as their monthly salary, I get around 55 million rials [$220] a month, and this is not fair at all.” The striker added that months could go by before subcontractors pay their employees’ wages, even as the laborers must work over 12 hours per day.

According to IndustriALL, an international union claiming to represent 50 million laborers in the energy, mining, and manufacturing sectors, living conditions for the contract workers are poor. The workers live on-site in unsanitary dormitories and eat low-quality food in their canteens. “Contractors also routinely underpay social security contributions by misclassifying workers, which affects their pensions, unemployment and sickness cover.”

As Middle East Eye has reported, the strikes’ organizing committee made seven demands, including “a salary of not less than 120 million rials ($480) and an increase in wages as inflation rises; a ban on the dismissal of workers; improved health and safety standards; and freedom of association and protest.”

Initially, subcontractors refused to meet strikers’ demands. A July 2021 news report claimed that the Tehran refinery, which is state-controlled, terminated 700 striking employees. However, a refinery spokesperson disputed that report, claiming a subcontractor it dealt with had laid off 35 employees. Eventually, some concessions were made, but laborers on scaffolding projects went on strike in June 2022, repeating several past demands. In September 2022, oil ministry employees, in turn, protested outside the ministry’s headquarters in Iran, reportedly “demand[ing] better wages and working conditions, and lower taxes as well as proper healthcare services.”

A critical question is whether permanent employees of NIOC and other firms run by the oil ministry will eventually also go on strike, protesting their own wage levels and in solidarity with their striking private-sector counterparts.

In 1979, strikes by both NIOC employees and contract workers in protest of low pay disrupted oil production, contributing to the fall of the monarchy and the success of the Islamic Revolution. With Iran’s economy currently in a tailspin due to regime mismanagement and U.S. sanctions, if broader strikes further reduced the oil revenues going into the regime’s coffers, the survival of the Islamic Republic itself could be imperiled.

Thus far, senior Iranian officials, including then-President Hassan Rouhani and then–Oil Minister Bijan Zangeneh, have tried to deflect responsibility for the strikers’ grievances. Both Rouhani and Zangeneh claimed in late June 2021 that the strikes were unrelated to the oil ministry. Rouhani tried to blame the subcontractors, and Zangeneh said the striking contract workers should direct their calls to the labor ministry, not his own. The oil minister added that his ministry would soon fix any issues regarding the pay of permanent workers. The regime has yet to use force or threaten to use force against the strikers.

Child Labor

Many severe types of child labor are permitted by Iranian law. While the law does not allow most types of labor for children under age 15 and limits what work children under 18 can do (e.g., no hard labor or night shifts), children under 15 may be employed as domestic servants or in agriculture, and some small businesses.

The authorities do not sufficiently implement child labor laws or monitor or penalize child labor. Children who work on the streets (street vendors, for example, many of whom are Afghans) are economically and sexually exploited, including by police, and some children have been compelled to become involved in begging rings. According to the U.S. Department of State, “the managing director of the Tehran Social Services Organization… [stated] in 2018 that, according to a survey of 400 child laborers, 90 percent were ‘molested.’”

Unpaid Wages

The failure of the state and private employers to pay wages on schedule, mainly due to the regime’s economic mismanagement and growing international isolation, has become a touchstone for recurring worker demonstrations.

According to the State Department, “many workers continued to be employed on temporary contracts, under which they lacked protections available to full-time, noncontract workers and could be dismissed at will… Large numbers of workers employed in small workplaces or in the informal economy similarly lacked basic protections… Low wages, nonpayment of wages, and lack of job security due to contracting practices continued to contribute to strikes and protests.” And via arbitration and as authorized by the Labor Ministry, employers have been given the right to interpret indefinite contracts as temporary. Consequently, reportedly over 90 percent of contracts in Iran are treated as temporary, leaving workers powerless and subject to their bosses’ caprice.

In August 2018, police reportedly arrested five employees of the Haft Tappeh sugarcane company and charged them with national security crimes amid protests over unpaid wages and benefits. Iranian authorities released the protesting employees after their labor representatives struck a deal with judiciary officials. However, according to Amnesty International, “in September of 2019, jailed labour rights activists Sepideh Gholian and Esmail Bakhshi were sentenced to, respectively, 18 years and 13 and a half years in prison and 74 lashes in relation to their participation in peaceful protests over unpaid wages at Haft Tappeh… and to public statements in which they said they were tortured in detention.” According to the Center for Human Rights in Iran, Haft Teppeh labor representative Ali Nejati is currently serving a five-year sentence.

Unemployment and Rising Prices

The bleak plight of workers goes beyond the regime’s lack of labor protections. Tens of millions of people remain trapped in an endless cycle of joblessness and poverty.

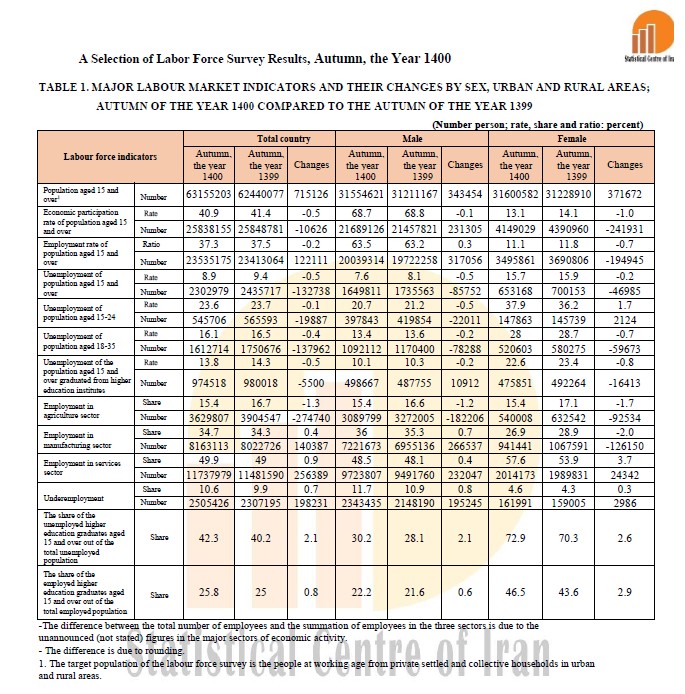

Per the Iranian Statistical Center, the official unemployment rate for the fourth quarter of 2021 stood at 8.9 percent, the women’s unemployment rate was 15.7 percent, youth (15–24) unemployment stood at 23.6 percent, and 16.1 percent of those 18 to 35 remained jobless.

Actual levels of unemployment are likely much higher. The Iran International news website has reported that the government’s definition of being employed includes people who work as little as one hour a week. The governor of the Iranian province of Khuzestan said in 2021 that “usually unemployment figures [in Iran] are not real” and Khuzestan’s actual unemployment rate is 45 to 50 percent.

Iranians are also sinking deeper into poverty due not only to high unemployment but to rising inflation, and the COVID pandemic, for which Iran served as an epicenter. According to a conservative estimate from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), annual inflation in Iran is 32.3 percent as of April 2022. The Free Workers’ Union of Iran lambasted the labor ministry in March 2021 for instituting minimum wage hikes that do not keep up with the actual inflation rate. Moreover, millions of Iranians get paid under the table, and therefore receive no benefits and do not receive government-mandated wage increases.

“More than 60 per cent of Iranian society live in relative poverty because the workers’ wages are enough for about a third of their costs of living,” stated Faramarz Tofighi, chief of the Islamic Labour Council’s wages committee, and “[h]alf of those who live below the poverty line struggle with extreme poverty.” A Statistical Center of Iran report from September 2020 states that half of Iranians live in poverty. The cost of staple foods like eggs, chicken, rice, beans, and vegetable oil has reportedly risen by 100 to 200 percent. Tellingly, the regime has stopped publishing poverty statistics.

Budget Battles

Iran’s hardship comes on the heels of repeated austerity budgets presented by former President Hassan Rouhani and current President Ebrahim Raisi. In March 2018, Rouhani sought a $104 billion budget that slashed popular subsidies for the poor. In late December 2018, Rouhani unveiled his proposed $47.5 billion budget for March 2019–March 2020, which, due to the impact of sanctions and the precipitous devaluation of Iran’s currency, was less than half the previous year’s budget. The 2019–20 budget proposal was premised on an optimistic forecast for oil exports, leading to a large budget deficit.

Rouhani’s March 2020–March 2021 budget proposal suffered from the same problem. It anticipated that Iran would sell about a million barrels per day of oil, even though at the end of 2019, Tehran was reportedly only exporting about 300,000. It also proposed a 13 percent tax increase that would bring revenues to almost two trillion rials, but Rouhani himself indicated that 1.5 trillion would be a more likely outcome. The parliament decisively rejected Rouhani’s budget in February 2020. However, two weeks later, after parliament speaker Ali Larijani asked Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei to intervene, Khamenei ordered that the budget take effect without parliamentary approval. The final budget did incorporate amendments by the parliament’s budget committee, the Guardian Council, and the Expediency Council that increased spending by 15 percent, including hikes to civil service wages and spending on defense, police, and development.

Even as Iranians suffered from increasing poverty, the government prioritized funding revolutionary guns over butter. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) budget was increased by over 60 percent—one-third more than Rouhani requested. Spending on the IRGC’s Basij volunteer militia also increased by more than 100 percent above Rouhani’s proposal and roughly a third more than the prior year.

In his first year in office, President Raisi has continued and sometimes intensified the government’s economic mismanagement of Iran. His budget for March 2022–March 2023 exacerbated austerity, poverty, and inflation while increasing funding for the regime’s power centers.

Total government spending decreased by 22 percent after adjusting for inflation. The regime increased the salaries of government employees and payments to pensioners by 10 percent in current rials, meaning that those groups’ incomes decreased in real rials. Raisi’s budget assumes a whopping eight-percent year-over-year growth in GDP (the IMF projected only three percent growth, and GDP has contracted in six of the prior ten years).

However, the regime’s security and propaganda arms flourish under the new budget. IRGC funding went up by 131 percent, the Basij’s by 45 percent, the Army’s Joint Staff’s by 60 percent, and the Army’s General Staff by an astonishing 977 percent. Spending on Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting increased by 46 percent. The budget also hiked funding for religious organizations, including the Seminaries Services Center (180 percent), the Waqf and Endowments Organization (67 percent), and the Islamic Propagation Organization (76 percent).

Rather than benefits to the public trickling down, they are flowing up, being gifted to the highest echelons of the Islamic Republic. Likewise, the supreme leader continues to draw from Iran’s National Development Fund to increase Iran’s defense budget. Thus, ordinary Iranians are being left on the margins of society while ‘millionaire mullahs’ enrich themselves and their patronage networks, and Iran continues to implement its hegemonic ambitions.

The bleak economic picture in Iran has laid bare the limits of the nuclear deal, which was expected to pay dividends to Iran in reconnecting the country, at least in part, to the global economy. While conservative elements of the Islamic Republic seek to lay blame at Washington’s doorstep for thwarting the fruits of the deal as an answer to the protesters, the structural problems inherent in Iran’s economy—for example, its banking sector’s role in the financing of terrorism and the prevalence of money laundering—are the true culprits. Iranian workers will continue to demand fair wages and improved working conditions, but as Iran’s ability to provide these public goods diminishes due to the regime’s mismanagement and increased isolation, it will likely rely increasingly on repression, ensuring continued unrest.

The Political Equation

It is significant that the first Iranian official to comment on the unrest in recent years was then-President Hassan Rouhani. But final authority and responsibility rests with the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who hasn’t been shy about blaming the Rouhani administration for the country’s woes. For example, in August 2017, the supreme leader chastised the Rouhani government about its statistics, saying, “the economic statistics presented [by the government] are based on scientific rules, but these statistics do not fully and comprehensively reflect the country’s real situation and people’s living conditions… [b]ased on these statistics, the inflation has been decreased from tens of per cent to under ten per cent, but has people’s buying power increased accordingly?”

Khamenei has adopted a hedging strategy—rarely taking responsibility for government decisions and passing the buck to whoever is president to avoid blame and preserve maximum flexibility for future political utility. We’ve seen this movie before with the Iran nuclear deal—while he endorsed the accord, he indicated his lack of trust in Washington to carry through on its commitments so as to be able to demonstrate his “wisdom” if he decided later on that the costs of remaining a party to the nuclear deal outweighed its benefits.

Lastly, the bleak economic picture in Iran has laid bare the limits of the nuclear deal, which was expected to pay dividends to Iran in reconnecting the country, at least in part, to the global economy. Conservative elements of the Islamic Republic will continue seeking to lay blame on Washington for thwarting the fruits of the deal as an answer to the protesters. But the structural problems inherent in Iran’s economy will dampen the ability of the authorities to make a difference.