Asghar Mir-Hejazi: The Supreme Leader’s Enforcer

Download PDFPage Navigation

Asghar Mir-Hejazi is one of the most influential actors in Iran’s establishment. But he flies under the radar of most Western coverage of Iran. This is because he represents the very essence of Iran’s deep state. Mir-Hejazi’s power stems from the longevity of his closeness to Iran’s supreme leader. His rise through the ranks of Iran’s intelligence community and the Office of the Supreme Leader have wielded him considerable stature in Tehran.

Asghar Mir-Hejazi’s Career

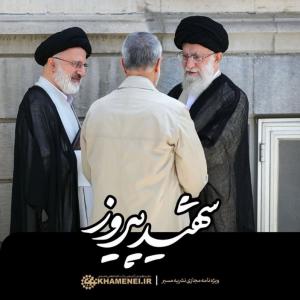

Photo of Asghar Mir-Hejazi, Qassem Soleimani, and Ali Khamenei

Photo of Asghar Mir-Hejazi, Qassem Soleimani, and Ali Khamenei

Mir-Hejazi was born on September 8, 1946, in Esfahan, Iran. He was educated for six years in Esfahan, and then underwent clerical training in Qom. After the founder of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, returned to Iran in 1979, Mir-Hejazi was a commander in the early Committee of the Islamic Revolution and became a founder of the Islamic Republic’s intelligence service. In 1983, Iran’s parliament approved the formation of the Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS). After its establishment, Mir-Hejazi became a deputy minister in MOIS, in charge of the Office of International Affairs. MOIS was established after three separate intelligence organizations—Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps intelligence, the Komitehs, and the Prime Minister’s Intelligence Office—were folded into one body. Mir-Hejazi became a deputy minister under Mohammad Reyshahri, the first intelligence minister of the Islamic Republic. He, in turn, served under Ayatollah Ali Khamenei when he was president and Mir-Hossein Mousavi as prime minister.

When Mir-Hejazi was at MOIS, its power was ascendant. According to a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) assessment from December 1987, Reyshahri “has acquired substantial power over the past two years as his ministry has gradually taken over internal security from the Revolutionary Guard and other revolutionary bodies.” It also indicated that he had “built a strong base in the Consultative Assembly, where he can command the support of about 100 of the 270 deputies.” Reyshahri used the ministry as a platform for his own ambitions, with some reports listing him in the 1980s as a potential successor to Khomeini. In a declassified document from 1986 in the files of the CIA, it cited his “bid to gain more influence at the expense of both [Akbar Hashemi] Rafsanjani and [Hossein-Ali] Montazeri.” Reyshahri, who had come to MOIS after holding judicial posts, was the son-in-law of the powerful Ayatollah Ali Meshkini, the first chairman of the Assembly of Experts. Thus Mir-Hejazi held a senior position in MOIS at a time when its minister as well as his father-in-law were powerful operators in the Iranian system, jockeying for position as Khomeini aged.

Mir-Hejazi was also on the scene as Reyshahri presided over the investigation, amid an internal power struggle, of Mehdi Hashemi, who was the brother of the son-in-law of Deputy Supreme Leader Ayatollah Hossein-Ali Montazeri. Hashemi was later executed, but this episode triggered a rift between Khomeini and Montazeri that ultimately impacted succession in the Islamic Republic as Montazeri, who was Khomeini’s designated heir at one point, lost his position.

After Khomeini died and Khamenei became supreme leader in 1989, Mir-Hejazi’s fortunes rose. Khamenei inherited the supreme leadership as a mid-ranking cleric in the shadow of Khomeini’s singular political and religious status. Additionally, Khamenei received the post in no small part due to Rafsanjani, who was at the time the powerful speaker of parliament and felt he could manipulate the new supreme leader. Feeling insecure, Khamenei was motivated to build his own power base in the Office of the Supreme Leader, bringing in figures like Mohammad Mohammadi Golpaygani as his chief of staff, and Mir-Hejazi as deputy chief of staff in charge of intelligence and security. Khamenei was likely familiar with Mir-Hejazi as their tenures overlapped when Khamenei was president and Mir-Hejazi was at MOIS.

Mir-Hejazi’s career was on the rise as Reyshahri’s waned after Khamenei’s succession. Reyshahri was soon replaced by Ali Fallahian as intelligence minister when Rafsanjani assumed the presidency. Thereafter, apart from a short stint as attorney general, Reyshahri assumed a number of less influential postings, for example, as representative of the supreme leader for Hajj affairs and as custodian of the holy shrine of Abdol Azim al-Hasani. This reflected Khamenei’s desire for control, and Mir-Hejazi, being dependent on Khamenei personally for most of his career and lacking an independent power base of his own, was a safe bet for the new supreme leader.

Throughout Khamenei’s tenure, there have only been glimpses of Mir-Hejazi’s handiwork and fingerprints in public. But he has been involved in the most consequential moments of Khamenei’s supreme leadership. Mir-Hejazi emerged as a messenger, conveying the supreme leader’s opinions and orders to other parts of the Iranian system, including the president, speaker of parliament, and chief justice. In the U.S. government’s sanctions designation of Mir-Hejazi in 2013, it said he is “considered the working brain behind the scenes of important events” and “is closely involved in all discussions and deliberations related to military and foreign affairs.” In a separate designation in 2020, the U.S. government also noted Mir-Hejazi “maintains close links to the IRGC’s Quds Force.” This can be seen in photographs of Iran’s supreme leader and the late Quds Force Commander Qassem Soleimani, where Mir-Hejazi is clearly visible engaging with Khamenei and Soleimani.

Photo of Mohammad Hassan Hejazi via Al-Arabiya

Photo of Mohammad Hassan Hejazi via Al-Arabiya

Mir-Hejazi appears in the files of the late Argentinian prosecutor Alberto Nisman who investigated Iran’s complicity in the bombing of the AMIA Jewish center in Buenos Aires in 1994. One document recounts Iranian involvement in the murder of Kazem Rajavi, a onetime Iranian ambassador to the United Nations who later became a dissident, in Switzerland in 1990. According to an investigation, a co-conspirator Hadi Najafabadi, who arrived in Geneva four days before the assassination and was seen as a trusted confidante of then-President Rafsanjani, placed calls to Mir-Hejazi’s office in Tehran from a hotel in Switzerland. He was seen as a “coordinator” of this operation. Thus Mir-Hejazi can be seen in this episode as playing a key role as a link between the Iranian leadership and the assassins.

Mir-Hejazi also participated in the deliberations leading up to the bombing of the AMIA Jewish center itself as a member of the Committee for Special Operations. According to the 2006 indictment in the case prepared by Nisman, “with regard to the committee’s role in the decision to carry out the AMIA attack, Moghadam stated that this decision was made under the direction of Ali Khamenei, and that the other members of the committee were Rafsanjani, Mir-Hejazi, Rouhani, Velayati, and Fallahian.” Mir-Hejazi is once again at the center of decision-making on security matters.

In researching this profile, UANI discovered that many media accounts cited the late IRGC commander Mohammad Hejazi, who served in a variety of senior roles, including as deputy commander of the Quds Force, as participating in these deliberations. However, a careful reading of the indictment clearly indicates that it was Asghar Mir-Hejazi, not Mohammad Hejazi, who was present at the Committee for Special Operations deliberations. These are two different men. Mohammad Hejazi is listed as Khamenei’s intelligence and security advisor in some reports. But in fact that was likely Asghar Mir-Hejazi, who serves in that position to this day. This is not to say that Mohammad Hejazi did not play a role in the bombing. According to some Israeli media accounts, citing international intelligence sources, Mohammad Hejazi played a role in planning the attack. But that is not necessarily the same function as Mir-Hejazi, who was involved in the decision-making as a part of the committee.

Later, Mir-Hejazi played messenger in August 2000 when he delivered a letter from Iran’s supreme leader to the parliament speaker, where Khamenei came out against a new press law which would deregulate the draconian limits on media in the Islamic Republic. This was a centerpiece of the reform agenda of Iran’s then-President Mohammad Khatami. Khamenei wrote, “it will be great danger to the national security and people’s faith if the enemies of the Islamic Revolution control or infiltrate the press. The present press law has prevented such disasters so far. The proposed bill is not legitimate, and amending it is not in the interests of the country.” In this episode, Mir-Hejazi served as Khamenei’s enforcer in sensitive political matters directly impacting the equities of multiple institutions in Tehran.

Mir-Hejazi has also been intimately involved in government appointments. Former Foreign Minister Javad Zarif recounted in his memoirs that when he was named Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations in 2002, Khamenei had told Mir-Hejazi that Zarif was “the best choice to be sent to New York” and that when his name as U.N. ambassador “is officially presented to us, you [Mir-Hejazi] officially accept that [on our behalf].”

Mir-Hejazi was also later sanctioned by the European Union in 2012 and the United States in 2013 for his role in suppressing dissent over the disputed reelection of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as Iran’s president in 2009. In the European Union’s sanctions designation, it referred to him as “part of the Supreme Leader’s inner circle, one of those responsible for planning the suppression of protests which has been implemented since 2009.” Likewise, the United States considers him “one of the primary officials in the oppression following the June 2009 post-election unrest” and that he “used his influence behind the scenes to empower elements from Iran’s intelligence services in carrying out violent crackdowns against the Iranian people.” It is in this context that Mir-Hejazi likely played a key coordinating role from the Office of the Supreme Leader in relaying orders to the IRGC, Basij, and MOIS in the repression.

There are also glimpses of Mir-Hejazi’s role in the birth of the secret back channel between Iran and the United States brokered by Oman during the presidency of Barack Obama. According to an interview with Ali Akbar Salehi, who served as foreign minister at the time, Salehi recounted a letter from the then Sultan of Oman to Iran’s supreme leader. He said, “it was in this letter that it became apparent that the Americans really want to enter a serious dialogue…After this letter was received, I got in touch with the Office of the Supreme Leader, and I told Mr. [Mir-]Hejazi that such a letter exists, and how I should deliver it. Mr. [Mir-]Hejazi said he will let me know. He later got in touch and said that we should give the letter to Mr. [Ali Akbar] Velayati. I gave the letter to Mr. Veleyati and he delivered it to the supreme leader.” In this episode, Mir-Hejazi is seen as a gatekeeper for Khamenei.

Mir-Hejazi also reportedly played a role in the elevation of Khamenei’s longtime associate Ahmad Jannati as the chairman of Iran’s Assembly of Experts in 2016, despite Jannati just meeting the threshold for entry into the Assembly after the election that year. According to Al-Arabiya, Mir-Hejazi met with the then chairman of Iran’s Expediency Council, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, when it appeared Jannati would lose the election, and suddenly another rival candidate was removed from contention, which paved the way for Jannati to assume the chairmanship.

In recent years, revelations about Mir-Hejazi’s son(s) have surfaced. His son, Mohammad Hassan Hejazi, has reportedly been a Quds Force operative tasked with intelligence collection and has managed operations in Europe, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East. Al-Arabiya reported that Hejazi had a “passion for expensive cars and fine dining.”

In another episode, a son of Mir-Hejazi named “Seyed Mir-Hejazi” surfaced in the case of former FBI agent Robert Levinson, who disappeared in Iran in 2007. It is unclear if this is the same Mir-Hejazi as above or another son of the Ayatollah’s deputy. According to Barry Meier in his book The Missing Man, Mir-Hejazi’s son reportedly offered at one point to secure Levinson’s freedom in exchange for money and even floated arranging for a phone call with Levinson. Meier described Seyed Mir-Hejazi’s routine: “[Mir-]Hejazi, who didn’t speak English, would arrive accompanied by a translator, another man who said he was an officer in the Quds Force, and a small coterie of attractive Iranian women. Each time he promised to deliver proof that Bob was alive and then never did.” According to Meier, the “FBI suspected he was acting with his father’s approval, because Iranian operatives were spotted keeping watch on the hotels where he met…” with an intermediary. But the FBI also thought it possible that Mir-Hejazi “was simply using the [indermediary] to underwrite his jaunts outside Iran while his father’s underlings monitored the American government’s interest in Bob’s case.” Mir-Hejazi’s son had at one point even suggested Khamenei had authorized him to broker an exchange, and proposed an escape plan via a Swiss Embassy vehicle for Levinson, according to Meier. But then the plan fell through as the Swiss Embassy warned he was not to be trusted because of his Asghar Mir-Hejazi’s role in the intelligence service, the book recounted. This situation reveals the closeness of Mir-Hejazi to Iranian security services, the luxurious lifestyle of his family, as well as the shadowy circles in which he operates.

Conclusion and Future Prospects

Having worked in the Office of the Supreme Leader since 1989, Asghar Mir-Hejazi will likely continue to serve at Khamenei’s side until his death. Mir-Hejazi may also play an important part should Khamenei ever become incapacitated and unable to discharge his duties. Nevertheless, some Iranian media accounts claim that there has been competition between the head of the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization, Hossein Taeb, and Mir-Hejazi, with Taeb as a potential replacement. In the end, Mir-Hejazi’s power may wane when a new supreme leader takes the stage, as those formerly close to Khomeini found themselves iced out when Khamenei ascended to the leadership.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox.

Eye on Iran is a news summary from United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI), a section 501(c)(3) organization. Eye on Iran is available to subscribers on a daily basis or weekly basis.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox

The Iran nuclear deal is done. And the world's biggest companies have already visited Tehran ready to strike a deal when sanctions end. These businesses will add even more to Iran's bottom line. And that means continued development of nuclear technologies and more cash for Hamas and Hezbollah.