Organizational Chart of the Islamic Republic of Iran

Parliament

Iran’s parliament comprises of 290 elected representatives. The power of the legislature is limited and has been weakened through the years by other state branches, namely the Office of the Supreme Leader. Apart from the standing seat the speaker of parliament has on the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), the parliament has no direct control over foreign or nuclear policy—apart from the platform the legislative chamber provides for its membership to opine on the nuclear file and Iran’s adversaries and allies in the media. This comes in the form of membership on parliamentary oversight committees like the national security and foreign policy committee. While the parliament technically confirms the president’s nominations for ministerial positions, many of the most sensitive posts—foreign affairs, intelligence, and defense—require preapproval from the Office of the Supreme Leader. Parliament also approves the budget and treaties, can impeach ministers—although again in the more critical ministerial roles, the supreme leader’s consent is usually required for such a step—and issues formal oversight questions to Iran’s government.

In practice, other state organs, like the Office of the Supreme Leader and the Supreme Economic Coordination Council, which is comprised of the speaker of parliament, chief justice, and president, have limited parliamentary authority. For example, in 2000, Iran’s supreme leader ordered that a press law that was aimed at reforming the draconian limits on Iranian media not be debated in the legislative chamber. In November 2019, days after the increase in the price of gasoline, which triggered protests, the supreme leader reportedly intervened to dissuade parliament from opposing the controversial price increases, after the Supreme Economic Coordination Council approved them. Likewise, parliament is often manipulated by other state organs, like the SNSC, for their own ends in the Iranian system. In December 2020, despite President Hassan Rouhani’s reported opposition, parliament passed a law, which was also approved by the Guardian Council, ordering expansion of Iran’s nuclear program and limiting inspections if U.S. sanctions were not lifted within two months. This coincided with the election of Joe Biden as president of the United States and represented a version of Iran’s own maximum pressure campaign to force the United States to reenter the nuclear deal on Iranian terms. The SNSC Secretary Ali Shamkhani, who is technically appointed by Rouhani but is also the personal representative of the supreme leader, supported the law, and there were accusations that the SNSC secretariat lobbied parliament in support of the legislation, without Rouhani knowing about the move. The nuclear law would not have passed parliament or the Guardian Council, whose members are named by the supreme leader, without the greenlight from Khamenei, not to mention the SNSC supporting—and some subunits even lobbying—for the law. Thus, parliament can be empowered or disempowered depending on the needs of the Iranian system.

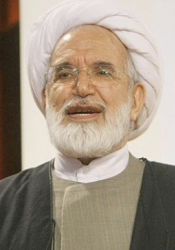

The speaker of parliament does have a significant political role in the Iranian system. However, since 1979, the only speaker of parliament who was able to use the office to successfully advance his career was Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who became president after serving as speaker and occupied a unique revolutionary role in the Islamic Republic. His successors—Mehdi Karroubi, Ali Akbar Nategh Nouri, Gholam-Ali Haddad-Adel, and Ali Larijani—did at times seek higher office, namely the presidency, but lost, and in some cases, were humiliated by being disqualified from running by the Guardian Council. The incumbent speaker of parliament, Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, does have presidential ambitions. But the track record of his predecessors raises questions of whether he will be able to ever successfully secure that office after serving as speaker.