Who Will Be Iran's Next Supreme Leader?

Download PDFConstitutional Underpinnings

Iran’s constitution provides broad guidance on the characteristics sought in candidates for the position of supreme leader. Article 5 stipulates that the ideal individual be: “just, pious, knowledgeable about his era, courageous, a capable and efficient administrator…” Article 109 elaborates that the individual should have “[s]cholarship, as required for performing the functions of religious leader in different fields; required justice and piety in leading the Islamic community; and right political and social perspicacity, prudence, courage, administrative facilities, and adequate capability for leadership.” It’s this conglomerate of religious, administrative, and political qualities that will prove pivotal in determining the right figure for the job.

When the supreme leader dies or is incapacitated, the Assembly of Experts is constitutionally charged with selecting his successor. It’s possible that in the interim, Iran will form a leadership council comprised of officials like the head of the judiciary, the president, and a member of the Guardian Council selected by the Expediency Council, while the key stakeholders in succession—like the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Shiite clergy—build consensus.

The Iranian people elect members—88 Islamic jurists—to the Assembly of Experts every eight years and it has a leadership board and six subcommittees. There is a subcommittee within the Assembly which oversees the work of the supreme leader—but its actual authority to provide oversight remains in question given the singular power of the supreme leadership in Iran.

Precedent

In 1989, when the last succession process took place, the Islamic Republic found itself in a challenging situation. Ruhollah Khomeini had spent much of his decade in power with a designated successor—Hussein-Ali Montazeri. It was Montazeri who had the requisite clerical standing—grand ayatollah—to be considered the rightful heir to the Khomeini legacy. But Montazeri had a series of disagreements with Khomeini over politics and policy, resulting in Khomeini questioning even his religious credentials. Because of this rupture, when Khomeini died in 1989, Iran was without an heir apparent.

The first choice among many in the Assembly of Experts was Seyyed Mohammad Reza Golpayegani, a grand ayatollah and one of the most revered senior Shiite clerics in Iran. But Golpayegani fell short of the necessary support from the Experts. The Islamic Republic even briefly considered forming a leadership council comprised of figures like then-President Ali Khamenei, the head of the Assembly of Experts Ayatollah Ali Meshkini, and the head of the judiciary Abdul-Karim Mousavi Ardebili. Finally, then-Speaker of Parliament Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani put his finger on the scale in favor of Ali Khamenei as Khomeini’s successor.

Many in the clerical establishment felt Khamenei would be a placeholder appointment. A video of the Assembly of Experts recently resurfaced, which indicates that Khamenei was only supposed to be supreme leader temporarily—for one year—due in part to his inferior religious credentials as a hojatolislam, rather than as an ayatollah. As Khamenei himself admitted in 1989, “based on the constitution, I am not qualified for the job and from a religious point of view, many of you will not accept my words as those of a leader.” Khamenei became the permanent officeholder after the passage of constitutional amendments that reduced the religious qualifications required to assume the supreme leadership.

As of January 2019, according to Iranian media reports, the Assembly Experts has formed a committee to vet candidates for the next supreme leadership. Only current Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has access to the dossiers compiled by the committee.

Candidates

This resource is divided into first, second, and third tier candidacies for the supreme leadership. UANI has decided to designate individuals as first tier contenders because they have all commanded at least one branch of government in Iran; all hold an equivalent or higher religious rank as compared to Ali Khamenei at the time he ascended to the supreme leadership; and/or have experience in electoral politics. UANI defines second tier aspirants as those who lack wide-ranging administrative experience but whom, by virtue of familial connections, public profile, or membership or leadership within state organs, may eventually enter the decision-making equation. UANI defines third tier candidates as dark horses—those clerics with a more limited public profile, no significant record of administrative experience, but who command consideration by virtue of ties to the current supreme leader or a position within Iran’s religious hierarchy. Candidates who are older than the current supreme leader—like longtime Chairman of the Guardian Council Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati—have not been included given the uncertainty of their longevity and the likelihood that the Islamic Republic will want its third supreme leader to serve for at least a decade, as did Ruhollah Khomeini from 1979-89.

First Tier Candidates

Ebrahim Raisi

Conservative cleric Ebrahim Raisi, born in 1960, has been a fixture of the Islamic Republic’s establishment for decades. Like Supreme Leader Khamenei, Raisi hails from the city of Mashhad, and his extensive political and familial connections to Khamenei and his inner circle are the key to understanding his rise to prominence. Many analysts judge that some elements of the Iranian system are grooming Raisi as Khamenei’s designated successor.

Raisi first encountered Khamenei as a young clerical student in the holy city of Qom at the time of the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Raisi took part in an elite program, which featured courses in Islamic governance, and Khamenei was one of his teachers. Raisi began his career as a prosecutor at age 20, and rose through the ranks of the judiciary by demonstrating loyalty to Iran's revolutionary principles and a willingness to sentence dissidents and political prisoners to death. Most notably, in 1988, he was a member of a four-man panel that sentenced thousands of dissidents and leftists to death. Raisi went on to become deputy chief of the judiciary under Sadegh Larijani and then attorney-general from 2014-16. Attorney-general is an important post in the Islamic Republic—multiple former intelligence ministers have held the post after serving at the helm of the intelligence ministry.

Raisi is married to the daughter of Ayatollah Alam al-Hoda, a reactionary cleric also from Mashhad, who has been a key Khamenei ally since he became supreme leader. Raisi also counts Khamenei's son, Mojtaba, as a prominent backer. These family connections have cemented Khamenei's trust in Raisi and boosted him throughout his career.

In March of 2016, Supreme Leader Khamenei tapped Raisi to head Astan Quds Razavi, Iran's largest charity and the overseer of the Imam Reza Shrine, one of the holiest sites in Shiite Islam and a large source of revenue for the regime. Raisi's appointment offered him the opportunity to court powerful backers, and to build a patronage network of his own. He was once pictured with senior Iranian military commanders seated at his feet, an image which bolstered his authority.

In 2017, Raisi emerged as a presidential candidate, challenging incumbent President Hassan Rouhani. While Raisi lost the race, his entry into electoral politics gave him an opportunity to build a public, electoral brand—an important qualification, constitutionally, in the selection of a supreme leader. Raisi shares Khamenei’s mistrust of the West, favors a confrontational posture, is a populist rhetorically, and promotes efforts to build a resistance economy in Iran. For instance, on April 26, 2017, he stated, “[t]oday Americans are afraid of the word ‘Iran.’ ...This is the solution. The solution is not backing down. We must force them to retreat.” Raisi struck an economic populist tone throughout the campaign, calling for the amelioration of growing income inequality, pledging to increase cash subsidies to poor Iranians, and railing against corruption, which he attributed to Rouhani’s presidency.

Also indicative of the effort to elevate his profile, Raisi was Khamenei’s choice to head Iran’s judiciary, succeeding Sadegh Larijani in 2019. Notably, some reformists, in addition to Raisi’s more conservative supporters, cheered his appointment because they hoped Raisi would initiate institutional reforms to make the judiciary more efficient and less corrupt, given the scandals that swirled around former Chief Justice Sadegh Larijani. After taking office, Raisi increased his profile—spearheading an anti-corruption campaign that ensnared top regime officials, including an aide to the former chief justice. Speculation has mounted that Raisi has launched this campaign, in part, to eliminate Larijani from contention as a potential candidate for the supreme leadership. Raisi’s judiciary also targeted Rouhani allies in the last months of his tenure—with the brother of his First Vice President Eshaq Jahangiri, his Information and Communications Technology Minister Mohammad-Javad Azari Jahromi, his Vice President for the Environment Issa Kalantari, and his former Vice President for Women and Family Affairs Shahindokht Molaverdi all facing legal troubles. Such efforts are another front in Raisi’s battle to marginalize his political opponents. The U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned him in November 2019 as a member of the supreme leader’s inner circle under Executive Order 13876, and also cited his role in political repression in the Islamic Republic.

In August 2021, Raisi assumed Iran’s presidency after mass disqualifications by Iran’s Guardian Council—including of leading politicians in the Islamic Republic like former Speaker of Parliament Ali Larijani and then First Vice President Eshaq Jahangiri. This produced record-low voter turnout in the June election, heightening the Iranian people’s distrust of the system. Analysts assess that this heavy-handed approach was due to the desire by Iran’s supreme leader to ensure Raisi held the presidency during a potential leadership transition in the coming years given Khamenei’s old age.

After taking office, Raisi has stuck very closely to Khamenei’s world view—envisioning the formation of a resistance economy to neutralize sanctions, prioritizing development of economic and political relations with the region, and deepening partnerships with China and Russia. Indeed, Raisi has been pictured in Khamenei-like settings—praying over the graves of martyrs—as well as sporting similarly-styled clerical garb as the supreme leader, complete with a walking stick and keffiyeh. The majority of Raisi’s administration—which is the most sanctioned and wanted since 1979—has close ties to Khamenei, especially Raisi’s First Vice President Mohammad Mokhber, who headed financial conglomerates controlled by Khamenei’s office, and Deputy Foreign Minister for Political Affairs Ali Bagheri Kani, whose brother is married to the supreme leader’s daughter.

Religiously, while Raisi is a hojatolislam, Khamenei held that rank before he ascended to the supreme leadership. But the Iranian press is already giving him a promotion to ayatollah, following the precedents set by Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi and Sadegh Larijani after they assumed the helm of the judiciary. This trend has continued with Raisi as president, with the Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA), which is controlled by the government, referring to him as an ayatollah as well, in addition to Raisi’s official presidential website. However, Iran’s supreme leader has not gone that far, continuing to refer to Raisi as a hojatolislam. Politically, Raisi’s winning presidential campaign has bolstered his stock as a candidate for the supreme leadership, after a loss in 2017. This presidency will allow him to expand his political brand and network, and will position him with significant constitutional authority should Iran’s supreme leader pass away during his presidential tenure and an interim leadership council is formed thereafter. Raisi serving as the deputy chairman of the Assembly of Experts further augments his considerable institutional power. But there are risks for Raisi during his presidency, especially given his predecessors emerging from the position diminished as the office absorbs most of the accountability in the Iranian system. Administratively, Raisi is arguably the most qualified individual in terms of resume to succeed Khamenei. No other cleric will have commanded two branches of Iran’s state—the judiciary and presidency.

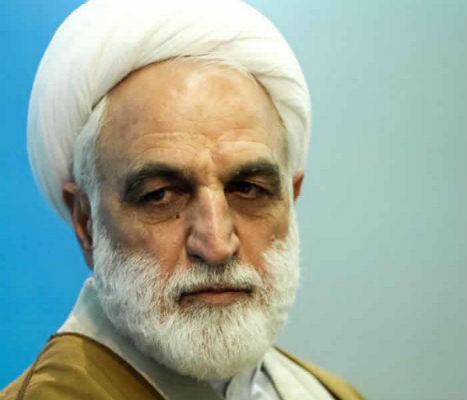

Gholam Hossein Mohseni Ejei

Gholam Hossein Mohseni Ejei, born in 1956, is a hojatolislam, although some reports refer to him as an ayatollah. Mohseni Ejei has spent his career in Iran’s judiciary and intelligence apparatuses—he served as a minister of intelligence under President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, attorney-general, and first deputy chief of and spokesman for the judiciary. He is currently chief justice, with Iran’s supreme leader naming him to the post in 2021.

Significantly, Ahmadinejad fired Mohseni Ejei as minister of intelligence due to his perceived closeness with the supreme leader after a disagreement over Ahmadinejad’s choice for first vice president, Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei. Many leading clerics also consider Mashaei as questioning of and undermining their role in Iran. However, the judiciary, an organ under the complete control of Ayatollah Khamenei, quickly took Mohseni Ejei under its wing.

The U.S. government sanctioned Ejei in 2010 for his role in suppressing unrest during the Green Movement of 2009. According to the U.S. Treasury Department, “Mohseni Ejei has confirmed that he authorized confrontations with protesters and their arrests during his tenure as Minister of Intelligence. As a result, protesters were detained without formal charges brought against them and during this detention detainees were subject to beatings, solitary confinement, and a denial of due process rights at the hands of intelligence officers under the direction of Mohseni Ejei. In addition, political figures were coerced into making false confessions under unbearable interrogations, which included torture, abuse, blackmail, and the threatening of family members.” Mohseni Ejei also stands accused of biting a journalist during a fight at a meeting of a press advisory council in Iran. As Radio Free Europe found in 2009, Mohseni Ejei’s website even included the infamous incident in his official biography at one point.

Mohseni Ejei served as deputy chief justice under both Raisi and his predecessor. Significantly, there are reports that Mohseni Ejei does not get along with Raisi—Raisi never had the chance to play a role in selecting his own new deputy chief justice during his time as chief of the judiciary.

Religiously, Mohseni Ejei has the requisite religious qualification, given he is a hojatolislam—a similar ranking that Khamenei held upon his ascension as supreme leader. Politically, Mohseni Ejei has developed a public following given his high-profile appointments within the Islamic Republic. Additionally, Ahmadinejad removing him from his post as intelligence minister may be attractive to many in the clerical establishment, given their distrust of the former president. However, Mohseni Ejei does have political baggage as he is one of the most feared members of the Iranian establishment. Administratively, Mohseni Ejei’s role as chief justice positions him as a potential contender for the supreme leadership given that many of his predecessors themselves have been considered candidates over the last few decades. The chief justice also plays a constitutional role on an interim leadership council—should one be formed upon Khamenei’s death—and has a seat on the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC). Thus, this provides Mohseni Ejei with a significant platform institutionally. Mohseni Ejei’s path to power is similar to that of Ebrahim Raisi—holding the positions of attorney-general, deputy chief of the judiciary, and finally chief justice. However, Raisi has a superior resume given his command of two—not just one—branches of Iran’s state.

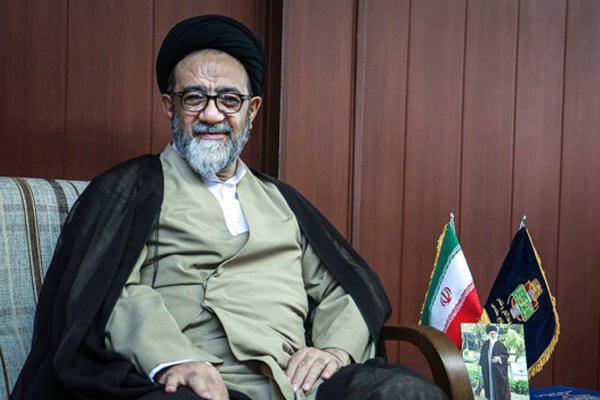

Sadeq Amoli Larijani

Sadeq Larijani, who was born in 1960 in Iraq, is a member of the Larijani dynasty—his father was a grand ayatollah, his brother Ali has served as speaker of the parliament, and his other brother, Mohammad-Javad, was a longtime diplomat for the Islamic Republic and served as secretary-general of Iran’s High Council for Human Rights. According to one account, his father-in-law, Grand Ayatollah Hossein Vahid Khorasani, opposed Ali Khamenei’s elevation as a source of emulation, and once even told Khamenei, “[y]ou be the sultan, but leave marjaeiyat to others.” Many consider the remark as questioning Khamenei’s religious credentials as supreme leader. Ironically, like Khamenei’s ascension from the president to supreme leader, Larijani himself started his tenure as head of the judiciary as a hojatolislam before Iranian news outlets suddenly began referring to him as an ayatollah later on. Most importantly, Larijani’s decade as head of the judiciary has provided a platform for wide-ranging administrative experience. There were even rumors that Larijani would be a candidate to succeed Ahmad Jannati as head of the Guardian Council, given that Jannati is a nonagenarian.

Electorally, Larijani has proven his mettle after winning a seat on the Assembly of Experts in 1999. Khamenei also gave him a seat on the Guardian Council, which vets candidates for state elections. Likewise, in a nod to Larijani’s continued status as a favorite son of the Islamic Republic, the supreme leader named him in 2019 as the new chairman of the Expediency Council, which is tasked with resolving disputes between parliament and the Guardian Council. In this new role, Larijani has been able to name a loyal figure, Mohammad Bagher Zolghadr, as secretary of the Expediency Council, following Mohsen Rezaei’s elevation as vice president for economic affairs, thus enhancing his control of the institution. Rezaei had served as secretary for decades.

In addition to his solid resume, Larijani fits well within the Islamic Republic’s prevailing governing ideology. He once stated, “[w]e support a society which is based on the spirit of Islam and religious faith, in which Islamic and religious values are propagated, in which every Koranic injunction and the teachings of the Prophet of Islam and the Imams are implemented. It will be a society in which the feeling of servitude to God Almighty will be manifest everywhere, and in which people will not demand their rights from God but are conscious of their obligations to God (Jahanpour).”

Nevertheless, Larijani’s career hasn’t been without controversy. Then-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad accused the Larijani family of monetizing their positions of trust in the government. For example, in 2013, Ahmadinejad showed a video to lawmakers depicting Fazel Larijani, another brother of Sadegh, soliciting a bribe from a member of Ahmadinejad’s administration in exchange for convincing Ali Larijani, then-speaker of the parliament, to support a pet project. Sadegh Larijani has also feuded with President Hassan Rouhani. There was speculation in Tehran that Larijani maintained illicit bank accounts totaling $77 million. Some parliament members even accused Larijani of depositing bail funds into his personal bank accounts, with one claiming Larijani held 63 such accounts. After he stepped down from the judiciary, Larijani was a focus of his successor Ebrahim Raisi’s anti-corruption probe, with his former top deputy, Akbar Tabari, being implicated.

Separately, in 2018, Sadegh Larijani was sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department under Executive Order 13553 for human rights abuses. According to the U.S. government, “[a]s head of Iran’s [j]udiciary, Sadegh Amoli Larijani has administrative oversight over the carrying out of sentences in contravention of Iran’s international obligations, including the execution of individuals who were juveniles at the time of their crime and the torture or cruel, inhumane, and degrading treatment or punishment of prisoners in Iran, including amputations.” Lastly, during the populist unrest which continues to sweep across Iran, protesters have at times focused their ire on Larijani personally.

The allegations of corruption have left a black mark on Larijani’s stock as a supreme leadership candidate. Additionally, following the Guardian Council’s disqualification of his brother Ali Larijani as a candidate in the 2021 presidential election, Larijani abruptly resigned from the Council. While he retains his role as chairman of the Expediency Council—and this makes it difficult to completely discount him as a contender for the supreme leadership—his stock within the Iranian establishment has clearly fallen as Iran’s supreme leader seeks to consolidate control ahead of the leadership transition.

Hassan Rouhani

Although President Rouhani hails from the pragmatic wing of Iranian conservative politics, he is a loyal regime insider committed to upholding Iran’s revolutionary Islamist ideology. Rouhani has held numerous top positions in Iran’s political, security, and clerical echelons during his decades-long career, including stints as president, secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council under two different presidents, and lead nuclear negotiator with the European Union (EU) from 2003-05. He is also a sitting member of the Assembly of Experts. While Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei retains sole authority over virtually all Iranian foreign policy and nuclear decisions, President Rouhani was a reliable soldier in defending and implementing the supreme leader’s dictates. Rouhani infamously boasted in his 2011 memoir that he had succeeded as Iran’s chief negotiator in covertly advancing Iran’s enrichment efforts under the cover of negotiations with the EU from 2003-05.

While in office, Rouhani denigrated the United States and Israel, praised Hezbollah and other terrorist proxies, and backed Iran's regional adventurism. However, compared with Iranian hardliners, Rouhani has pursued a tactically pragmatic approach, at times favoring expanding civil liberties domestically and economic and diplomatic engagement with the West in order for Iran to maintain its image internationally while preserving its regime and spreading the Islamic Revolution.

Rouhani’s principal achievement in office was the nuclear deal his administration reached with the P5+1 countries in July 2015, which granted Iran sanctions relief and a windfall of more than $100 billion in exchange for accepting temporary constraints on its nuclear program. However, in the aftermath of the U.S. withdrawal from the accord, the president was under a great deal of pressure from hardline elements in the regime. With the rial rapidly losing value against the dollar, inflation soaring, unemployment rising, and protests enveloping Iran, Rouhani’s political standing eroded. In fact, there were repeated accounts of Rouhani’s resignation. But the supreme leader intervened to prevent Rouhani’s impeachment by a conservative parliament. Nevertheless, Rouhani is a weakened political figure—with Khamenei siding with the parliament over Rouhani’s objections in implementing a new nuclear law in December 2020 to increase Tehran’s leverage as it seeks sanctions relief from the Biden administration. Khamenei voiced his displeasure with Rouhani’s administration at the end of his presidency, saying in July 2021 that “future generations should use this experience. It was made clear during this government that trusting the West does not work.” His office went on to release posters and videos that were critical of Rouhani. Indeed, Khamenei would not even allow Rouhani’s government to conclude the negotiations with world powers to revive the Iran nuclear deal. Rouhani also failed to receive any new state appointment after his presidency ended—even Mahmoud Ahmadinejad became a member of the Expediency Council following the end of his term as president.

Religiously, Rouhani is in a similar position to other contenders for the supreme leadership—like Ali Khamenei in 1989, he holds the rank of hojatolislam. Administratively, Rouhani is also qualified—he served two terms as president in addition to his collection of sensitive national security positions like secretary of the Supreme National Security Council. But politically, his toxic standing among hardliners, members of the IRGC, and many reformists—because of a lack of progress in easing social restrictions and the economic freefall—will hamper his ability to unite various factions in support of his candidacy. This is not to mention Khamenei’s scathing criticism of his government at the end of his tenure. Nevertheless, Rouhani remains relevant given his seat on the Assembly of Experts and his status as a former president.

Second Tier Candidates

Mojtaba Khamenei

Mojtaba Khamenei, born in 1969, is the second oldest child of current Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. His wife is the daughter of former Speaker of Parliament Gholam-ali Haddad-Adel. Some analysts argue Mojtaba does not even hold the rank of hojatolislam—though reports indicate he was taught by leading conservative ayatollahs including Mohammad Taghi Mezbah Yazdi and the late Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi. Some accounts describe him as a “gatekeeper” for his father, similar to Ahmad Khomeini's role for his father Ruhollah Khomeini. These same reports consider Mojtaba second-only to Mohammad Golpayegani, the head of the Office of the Supreme Leader, according to leaked U.S. State Department cables. The U.S. government confirmed his importance within the Supreme Leader's Office in November 2019, when he was sanctioned. According to the U.S. Treasury Department, “[t]he Supreme Leader has delegated a part of his leadership responsibilities to Mojtaba Khamenei, who worked closely with the commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Qods Force (IRGC-QF) and also the Basij Resistance Force (Basij) to advance his father’s destabilizing regional ambitions and oppressive domestic objectives.”

While occupying no official position in the Islamic Republic, officials have often portrayed him as an enigmatic kingmaker in Iranian electoral politics, interfering in both the 2005 and 2009 elections. Mehdi Karroubi, a former speaker of the Iranian parliament and then a candidate for president, alleged that Mojtaba had provided crucial backing to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2005 after initially backing Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf, causing Ahmadinejad’s rise in the first round of balloting. In 2009, reports claimed Mojtaba engineered Ahmadinejad’s victory and even instructed the Basij to aggressively clamp down on Green Movement demonstrators. In 2009, the British government froze a bank account rumored to belong to Mojtaba containing $1.6 billion, allegedly used to buy equipment for the Basij.

Despite the familial ties to Ayatollah Khamenei, Mojtaba will likely encounter religious, political, and administrative obstacles to becoming supreme leader. Opponents will seize on reports that he does not even hold the rank of hojatolislam in Iran. Politically, Mojtaba doesn’t have a natural constituency that other players—like Ebrahim Raisi—have going into the succession process. This will make it difficult for Mojtaba to argue he has the “capability for leadership.” But Mojtaba’s support within the IRGC could figure in his favor, especially if Raisi’s presidency encounters difficulties. There have also been unofficial attempts to increase his popularity as a potential supreme leader, with posters recently being found in Tehran promoting his candidacy. Administratively, while Mojtaba has experience working in the shadow of his father, learning at his feet, and being second-in-command in the Supreme Leader's Office, he lacks experience overseeing one branch of government. Even more challenging, Mojtaba is not an official member of a stage organ like the Guardian Council, Assembly of Experts, or the Expediency Council to compensate for his administrative shortcomings.

Hassan Khomeini

Hassan Khomeini, born in 1972, is the grandson of the founder of the Islamic Revolution and first supreme leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Hassan is the son of Ahmad Khomeini, who effectively served as chief of staff to his father during the Islamic Republic's nascent years. Following Ayatollah Khomeini’s death in 1989, Ahmad found himself sidelined. The Assembly of Experts had passed him over as a candidate for the supreme leadership—reports indicate Ahmad had wanted to succeed his father as supreme leader or at least be a member of a leadership council. In the years after his father’s death, Ahmad went on to become a custodian of Ruhollah Khomeini’s shrine and the supreme leader’s representative to the Supreme National Security Council.

After Ahmad died in 1995 from a heart attack, Hassan assumed control as custodian of Ruhollah Khomeini’s mausoleum. Iranian media reports indicate Hassan holds the rank of hojatolislam. Yet in 2016, when Hassan announced his candidacy for a seat on the Assembly of Experts, the Guardian Council barred him from running because his religious credentials could not be established due to his failure to participate in an examination. Some reports speculate his disqualification was due to his reformist leanings. At the time, Hassan wrote on Instagram, “All my support from top clerics has been ignored, as have been my religious publications.” In recent years, hardliners have also criticized Hassan Khomeini’s family for their extravagant lifestyle during a time of economic turmoil. Ahead of the 2021 presidential election, Hassan Khomeini’s name appeared on lists of potential candidates, including for the Executives of Reconstruction Party. However, reports later emerged that Iran’s supreme leader advised Khomeini against running for president in 2021, and he never registered his candidacy.

Religiously, while Iranian media technically refer to Hassan as a hojatolislam, the same rank that Ali Khamenei held before he ascended to the supreme leadership, the fact that the Guardian Council wouldn’t even bless his candidacy for a seat on the Assembly of Experts will hamper his candidacy for an even higher office. Politically, the Khomeini family has not had a role in the daily governance of the Islamic Republic in decades. However, Ruhollah Khomeini remains an enduring symbol as the founding father of the Islamic Republic. His family name, coupled with his standing among reformists, may make Hassan a topic of debate and discussion during a succession process. But opponents of his candidacy may point to Ruhollah Khomeini’s remarks from 1980 in which he said “I will that those who are related to me not enter political currents… I do order you based on Shariah not to enter political games.”

Administratively, Hassan Khomeini hasn’t overseen a branch of government or even served as a member of a state organ. This deficit stands in contrast to candidates like Mojtaba Khamenei, who serves as a trusted advisor to his father, and even Hassan’s father Ahmad, who served as aide-de-camp to Ruhollah Khomeini immediately prior to the 1989 succession. Thus, beyond symbolism, which is important, Hassan Khomeini lacks the confidence of many in the clerical establishment in addition to state management experience.

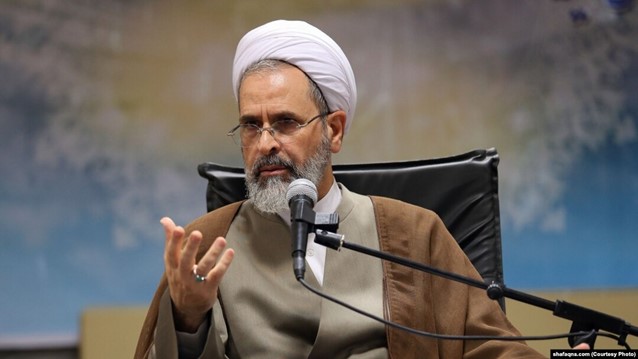

Ahmad Khatami

The cleric Ahmad Khatami was born in 1960. Khatami’s rise began in 1999 after winning a seat on Iran’s Assembly of Experts, and continued when Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei appointed him as Tehran’s substitute Friday Prayer Leader in 2005. It’s from this religious platform that Khatami built his brand—one of fire, fury, and fight.

Early on in his tenure as a Friday Prayer leader in 2006, his remarks in reaction to the Pope giving a speech in Germany that many found offensive to Muslims drew international attention. Khatami said “[t]he pope should fall on his knees in front of a senior Muslim cleric and try to understand Islam so he would never again say such absurd remarks.” At the same time, Khatami has used the tenets of Christianity as a means to attack America. Recently, he remarked, “I send my blessings to the Christians throughout the world, and I say to them: protect the honor of Christ. Unfortunately, the arrogant leaders who consider themselves Christians – and Trump says he hasn’t read anything but the New Testament all his life – bring disgrace upon this great prophet [Jesus]. [The Christians say:] Tell us what to do. [The Christians should] renounce America in a loud voice, and, like the [Iranian] people, they should say: “Death to America!”

Khatami has also engaged in bombastic international taunts. He routinely threatens Israel, recently warning “[t]he holy system of the Islamic Republic will step up its missile capabilities day by day so that Israel, this occupying regime, will become sleepless and the nightmare will constantly haunt it that if it does anything foolish, we will raze Tel Aviv and Haifa to the ground.” Khatami also brags about Iran’s nuclear prowess even under the auspices of the nuclear deal. In February 2019, Khatami claimed Iran “has the formula for building a nuclear bomb.”

The cleric has also cautioned the Iranian public about the dangers of Westoxification in Iran: “[T]oday they talk about legalizing alcoholic drinks, tomorrow they will say freedom of hijab, and the day after they will say we should have a referendum on the Islamic aspect of the regime. Know that you will take these dreams to your grave.” It’s this formula of using his clerical platform for headline-grabbing, hair-raising, shock value commentary that has endeared him to hardliners in the Iranian regime’s establishment.

In 2016, Khatami won a leadership role on Iran’s Assembly of Experts as secretary of its board of directors. Such a promotion could put Khatami in a key role to influence the process when the supreme leader dies and the succession process begins. In a sign that Iran’s supreme leader continues to value his loyalty, he named Khatami as a member of the Guardian Council in November 2020. Such a promotion has increased Khatami’s profile and importance within the system.

Religiously, Khatami’s rank as a hojatolislam wouldn’t disqualify him from consideration. Some Iranian news accounts even rank him as an ayatollah. Politically, Khatami’s voluminous record of public pronouncements on all kinds of matters of state leaves behind a paper trail with supporters and detractors alike. However, his lack of administrative experience in overseeing major institutions of state will hamper his candidacy.

Alireza Arafi

Born in Meybod in 1959, Ayatollah Alireza Arafi has risen steadily through the ranks under Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s supreme leadership. Some accounts suggest his father was a close friend of the founding Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini. He has occupied key Friday Prayer leadership positions in Meybod and later Qom. A review of Arafi’s official curriculum vitae also reveals a series of high-level appointments such as membership on the Supreme Council for Cultural Revolution, the head of the Islamic Seminaries of Iran, the former educational sciences faculty dean of the Imam Khomeini Educational Research Institute, and the chairman and former president of Al-Mustafa International University.

The common denominator in all these appointments is that his career has been spent at the cross-section between academia and the clergy. His associations with Al-Mustafa International University and the Imam Khomeini Educational and Research Institute are particularly important. Al-Mustafa International University was founded by Khamenei, and has branches in over 50 countries. Most significantly, the U.S. government has found that it enables “IRGC-QF intelligence operations by allowing its student body, which includes large numbers of foreign and American students, to serve as an international recruitment network.” Additionally, the IRGC has used Al-Mustafa International University to recruit for its Fatemiyoun and Zaynabiyoun Brigades for combat in Syria. Such experience for Arafi is important for two reasons: first, it offered him visibility as a leader of a Khamenei initiative, which has expanded rapidly through the years. Second, Arafi likely gained exposure to Iran’s proxy network as a result of his presidency of the university, on which the U.S. government levied terrorism sanctions in 2020.

Likewise, Arafi’s profile increased by virtue of his tenure at the Imam Khomeini Educational and Research Institute. This institute was led for many years by the late Ayatollah Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi. When he was alive, Mesbah-Yazdi, despite being older, was himself considered a contender to succeed Khamenei at one point. Thus Arafi likely increased his stature and network while at the institute.

Apart from these academic and religious roles, Arafi’s political experience has been more limited. Despite losing an election for a seat on the Assembly of Experts in 2016, in 2019, Khamenei named him to the Guardian Council, where he replaced Mohammad Momen, a moderate conservative. Such a plum appointment is noteworthy as Arafi plays a key role in vetting candidates for state elections and parliamentary legislation. This will diversify his resume, adding political heft.

In terms of ideology, Arafi has been a reliable conservative regime messenger, saying “America will take its wish for Iran to abandon production of military hardware to the grave.” In one Friday Prayer sermon in 2019, he pledged “We will stay with our imam and leader to the end, when we humiliate [global] arrogance. Together with the sayyed of the resistance we say: Oh great leader of the world of Islam, we will be with you until the end, when the arrogant people in the world are defeated, and Israel is erased.”

Religiously, Arafi has the status to be a contender to succeed Khamenei given his rank as an ayatollah. Politically, while he is a member of the Guardian Council, Arafi’s lack of a successful electoral track record—especially after his loss in the Assembly of Experts election of 2016—may present a hurdle to his candidacy. But his closeness to Khamenei coupled with his reliability as a conservative voice in the Islamic Republic could bolster his chances. Administratively, while Arafi has never headed a branch of Iran’s government, his management role as the head of Islamic Seminaries of Iran coupled with his tenure at Al-Mustafa International University potentially positions him to compensate for that deficit. Lastly, given that the current secretary of the Guardian Council Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati is a nonagenarian, there is speculation that Arafi could be a contender to replace him at the helm of the council. If this happens, Arafi’s stock as a contender to replace Khamenei will further increase.

Third Tier Candidates

Seyyed Mohammad-Ali Al-e Hashem

Unlike many other candidates for the supreme leadership, Hojatolislam Mohammad-Ali Al-e Hashem is not widely known outside Iran. However, his stock in the Islamic Republic has been rising ever since the Iranian media seized on his popularity as a Friday Prayer Leader in Tabriz. Many admirers see him as an accessible member of the mullahcracy—riding buses, taxis, and having lunch with university students, to cite a few examples.

Beyond his role as Friday Prayer Leader, Hashem is regarded as a loyal enforcer of Ayatollah Khamenei’s policies. In 2009, Khamenei appointed him head of the Iranian Army’s Political Ideology Section. Khamenei has hedged in his support for the nuclear deal, privately providing his blessing, while publicly proclaiming his lack of trust in the West. Hashem has adhered closely to Khamenei’s line, warning after the nuclear accord: “Today, the enemies have extensively plotted against the Islamic Republic so that they can influence and affect the country after the final agreement.” Hashem has also bragged about Iran’s leading role in the Middle East, arguing “[t]oday, the Islamic Republic of Iran is a decision-maker in the regional developments.”

Religiously, Hashem holds a similar clerical ranking—hojatolislam—as Khamenei did when he was named supreme leader. Politically, Hashem has a growing following given his fawning coverage in Iranian media. But he has never been a candidate for office, so outside Tabriz, his “capability for leadership” remains in question. Administratively, Hashem is trusted by Ayatollah Khamenei given his appointment as an ideological enforcer in Iran’s Army. However, Hashem is at a disadvantage because he has neither been the head of a branch of government nor has he been a member of state organs like the Assembly of Experts or the Guardian Council. But his dark horse candidacy, lack of an extensive public record, and lack of political baggage could serve him well in the elevation process.

Mohammad-Reza Modarresi Yazdi

Mohammad-Reza Modarresi Yazdi, born in 1955, holds the rank of hojatolislam, although some Iranian media reports refer to him as an ayatollah. Modarresi Yazdi has quickly become a favorite of current Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, with Khamenei appointing and reappointing him to the Guardian Council. He lost the election for membership in the Assembly of Experts in 2016.

Recently, before Ebrahim Raisi became chief justice, media reports indicated Modarresi Yazdi was on the shortlist to succeed Sadegh Larijani as judiciary chief. He’s been critical of clerics even supporting reformists in Tehran’s political life, speaking out against Grand Ayatollah Yousef Sanei for his support of Mir Hossein Mousavi during the Green Movement unrest of 2009.

Religiously, Modarresi Yazdi holds the requisite clerical ranking for the supreme leadership. Politically, he’s wounded because of his loss in the 2016 Assembly of Experts elections. However, administratively, the fact that Modarresi Yazdi’s candidacy was floated for the next chief justice of Iran, coupled with his longevity on the Guardian Council, makes him worthy of discussion for the post.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox.

Eye on Iran is a news summary from United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI), a section 501(c)(3) organization. Eye on Iran is available to subscribers on a daily basis or weekly basis.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox

The Iran nuclear deal is done. And the world's biggest companies have already visited Tehran ready to strike a deal when sanctions end. These businesses will add even more to Iran's bottom line. And that means continued development of nuclear technologies and more cash for Hamas and Hezbollah.