Hezbollah Imports Iranian Fuel for Lebanon

In August, Lebanon’s Central Bank Governor Riad Salameh announced an end to its fuel subsidies, which have drained the bank’s reserves since the country began descending into a financial crisis. The move, which was expected to cause already high fuel prices to quadruple, plunged Lebanon further into collapse. Shortly thereafter, the Lebanese government partially reversed Salameh’s decision, raising fuel prices by the comparatively low 66% instead, in a partial reduction of fuel subsidies. But this was only a partial fix, and a temporary one at that. The Lebanese government essentially had to borrow against its 2022 budget to continue this partial subsidization of fuel.

The detrimental impact of the rise in fuel prices has far-reaching implications for Lebanon. Long queues of customers are now regular sights at Lebanese gas stations, each waiting in line to fill up their gas tanks. Desperation has even resulted in killings over the increasingly scarce commodity. With no public transportation to speak of, fuel shortages have impacted unemployment rates, which are almost at 40 percent. The fuel shortage has also forced further cutbacks in Lebanon’s already-anemic supply of electricity. As a result, even hospitals have reduced their activities, and the country’s supply of potable water has also become jeopardized. Without electricity, supermarkets, restaurants, and private homes have been unable to store food, resulting in increased cases of food poisoning. Hospitals and the medical sector, which have already been forced to reduce their activities due to the electricity shortage, have been stretched to their breaking point.

Hezbollah has stepped in to help alleviate the impact of this latest Lebanese crisis. The group’s Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah had been offering to import fuel for Lebanon from Iran to combat the country’s energy shortages since June of 2020, claiming this would additionally alleviate the country’s dollar shortages because Tehran was willing to accept Lebanese Liras – instead of increasingly scarce dollars – for its fuel. He reiterated this proposal on March 18, 2021, saying he had not waited for permission from Lebanese officials to facilitate the deal. “I went and spoke to the Iranians, and they’re ready to supply Lebanon with fuel,” he claimed.

Now, Hezbollah seemed ready to deliver. On August 19, Nasrallah announced that the first ship – identified as National Iranian Tanker Company (NITC) owned and operated tanker FAXON (IMO: 9283758), carrying 280,000 barrels of Iranian diesel/gas oil, had set sail for Lebanon. Nasrallah had been promising to do precisely that since June 8, when he vowed that “if [Lebanon’s] fuel crisis continues without a solution, Hezbollah will buy ships of fuel from Iran and bring them to Beirut Port,” challenging the Lebanese government “to prevent the delivery of gasoline and diesel to the Lebanese people.”

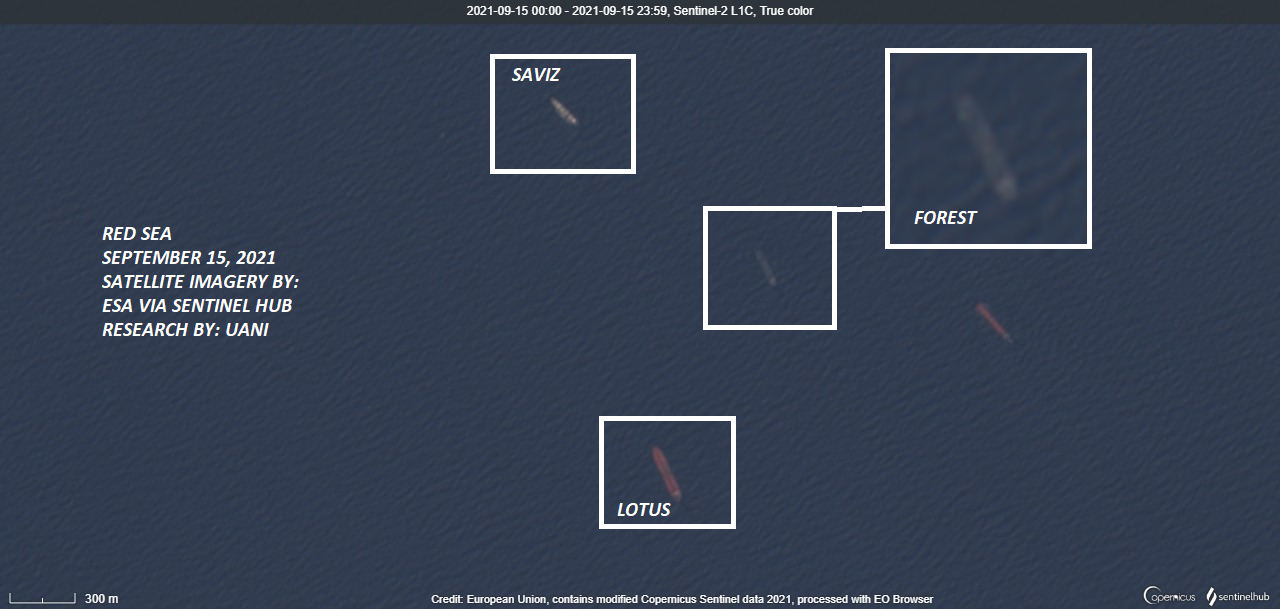

Within a week of announcing that the first Iranian fuel ship had set sail for Lebanon, Nasrallah said Tehran had agreed to send two additional fuel ships to Lebanon. The second ship is most likely the NITC owned and operated tanker FOREST (IMO: 9283760). Based on satellite imagery, from September 15, 2021, the vessel FOREST is anchored in the Red Sea near the Iranian ‘spy-ship’ SAVIZ along with the Iranian crude oil tanker LOTUS (IMO: 9203784). FOREST departed Iran’s Shahid Rajaee port on August 29, 2021, and is estimated to be carrying around 265,000 barrels of Iranian oil.

(Source: ESA via Sentinel Hub)

The third tanker is believed to be the FORTUNE (IMO: 9283746). FORTUNE, also owned and operated by NITC, began loading at Shahid Rajaee Port on September 14, 2021.

FAXON, FOREST, and FORTUNE are the same three Iranian-flagged tankers that were part of a fleet of five tankers that have brought Iranian gasoline to Venezuela on numerous occasions since May 2020. Following the deliveries to Venezuela, the United States sanctioned the captains of all five ships used to make the deliveries.

After almost three weeks of silence on the fate of the ships, Nasrallah announced on September 13 that the first of the three ships – the FAXON – had docked in Syria’s Banias Port the night before, and on September 14, it began discharging its cargo from at Bandar Mahshahr, Iran. He said the fuel would be transported to Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley by Thursday, where it would be “stored in specific fuel tanks in Baalbek,” one of the group’s stronghold cities.

According to Lebanese fuel importers and private generators, the FAXON’s cargo would only cover the country’s needs for three days. Nasrallah addressed this in his September 13 speech, saying, “we wanted to set priorities. Of course, the amount [of fuel we imported] won’t cover all of Lebanon’s needs, because we don’t want to enter competition with other companies. We’re capable of doing this, and I will comment on this later.” In the meantime, Nasrallah laid out Hezbollah’s plan to deliver targeted batches of the imported fuel to specific sectors, in two consecutive phases: a humanitarian phase during which fuel would be distributed for free, followed by a phase where the fuel would be sold. Nasrallah also said that the fuel – whether gifted or sold – would be delivered in batches, “in order to maximize benefit, we won’t give a requested full month’s supply upfront.”

Nasrallah said the first phase would have a “humanitarian” focus and would last between September 16-17 and October 16-17. Hezbollah plans to offer fuel “as a free gift” to help satisfy “all or part of” the needs of “public hospitals… nursing homes… orphanages…special needs homes, public water institutions…[poor] municipalities with wells, as well as firefighters, the civil defense, and the Lebanese Red Cross” for a month. During this month-long “humanitarian” phase, Nasrallah said the group would not reach out to the institutions in question but would wait for them to contact Hezbollah to receive fuel.

During the second phase, which would start after October 16-17, Nasrallah said the group would begin selling fuel “for an appropriate price” to private hospitals, drug and serum laboratories, drug and serum factories, grain mills, bakeries, supermarkets and coops, food industry factories, farming, and the owners of generators providing electricity subscriptions. For the time being, he noted, Hezbollah would not sell fuel on an individual basis, “but in the future, of course we will sell to individuals, particularly as the winter season approaches.”

As for the sale price, Nasrallah said Hezbollah would sell at lower than the total cost of purchasing and transporting the fuel. “We don’t want to make a profit, and we’re going to bear a specific portion of the cost, and we’ll consider it a gift to help the Lebanese people from the Islamic Republic of Iran and Hezbollah.” Nasrallah didn’t set the exact fuel price in his speech, saying that it would depend on the prices set by Lebanon’s Ministry of Energy. He noted that Hezbollah would announce that price by Thursday, September 16, at the latest, and that in any case, the group would sell the fuel in exchange for Lebanese Liras, not dollars.

Nasrallah said the responsibility for fuel distribution would devolve upon Amana Fuel Co., which, as he noted, has been designated by the U.S. Treasury Department. Amana Fuel Co. is one of many subsidiaries belonging to Atlas Holding SAL, also a designated entity, which is in turn controlled by Hezbollah’s Martyr Association, which itself ultimately answers to the group’s Executive Council.

Malek Yaghi, the head of Hezbollah’s “Fuel Office” in the Beqaa, appeared in a video shortly thereafter, explaining the group’s fuel distribution. Yaghi said the “convoy of victory” carrying the fuel to “break the [American] siege on Lebanon” would enter the country from Syria through the Beqaa Border Crossing. He said the convoy’s cargo would fill “dozens” of designated fuel tanks, whose contents would be distributed by Amana Fuel Co. According to Yaghi, Amana would set up Call Centers, where fuel orders could be placed.

Amana Fuel Co. listed the numbers of five such “call centers,” Lebanon’s 25 districts where fuel requests could be placed: the first call center would serve Beirut, and the Baabda, Aley, and Chouf districts in of the Mt. Lebanon Governorate, in the country’s center. The second call center would serve the districts of Tyre, Marjayoun, Bint Jbeil, and Hasbaya in south Lebanon. The third call center is designated to serve the Nabatieh, Sidon, Western Beqaa, Rachaya, and Jezzine districts, covering the rest of south Lebanon and the Beqaa Valley. The fourth call center will serve the districts of Baalbek and al-Hermel, which are Hezbollah strongholds in northeastern Lebanon, and Zahle, in the northern Beqaa Valley. The fifth call center will serve the districts of Northern Metn, Jbeil, Tripoli, Keserouan, Zgharta, Bcharre, Batroun, Koura, Dinieh-Al-Miniah, and Akkar, covering the northern portions of Mt. Lebanon, northward.

Per Yaghi, these call centers will collect the requisite information from potential fuel recipients and submit the orders to the corresponding stations belonging to Amana Fuel Co., which would then deliver the requested fuel. Yaghi also reiterated Nasrallah’s claim that Hezbollah had designated an oversight team to ensure that the fuel would only be delivered to institutions that were truly in need, and not to groups or individuals intending to hoard the materials or re-sell it on the black market.

The arrival of the FAXON’s shipment at Banias Port was met with notable silence from the U.S. administration, despite sanctions on Iran’s exportation of fuel, as well as sanctions on the FAXON itself. The only comment from U.S. officials on the matter came on August 19, when U.S. Ambassador to Lebanon Dorothy Shea effectively gave tacit U.S. approval for Hezbollah’s importation of fuel.

Ambassador Shea told Al-Arabiya at the time that she didn’t believe Lebanon needed fuel from Iranian tankers, citing “a whole bunch” of other tankers anchored off the country’s coast waiting to offload their cargo. Ultimately, she said, “Lebanon can do whatever it wants,” adding that, “I don’t think anyone is going to fall on their sword if someone’s able to get fuel into hospitals that need it.” Shea’s only objection was to note that “the Lebanese people deserve importers of fuel to distribute it equitably,” asking, “can you count on Hezbollah to do that?”

Whether Hezbollah will indeed distribute its Iranian-supplied fuel fairly remains to be seen. At the moment and at least on paper, however, the group's distribution plan seems to aim for equitable distribution, even considering the preferential treatment, which Hezbollah’s partisans and apparatchiks are almost certainly receiving. That’s not to say that the group has transformed into a humanitarian organization overnight. From a purely pragmatic standpoint, Hezbollah has an interest in preventing Lebanon’s further descent into chaos. Not necessarily because it has suddenly discovered some long-lost sense of Lebanese patriotism, but because further collapse will have a detrimental impact on the group’s fortunes and its ability to continue its military, political, and social growth. Chaos is not conducive to expansion.

Moreover, Hezbollah is interested in placating a periodically restive Lebanese street, including its supporters, who are suffering under the increasing weight of Lebanon’s unraveling. Periodically, fingers of blame for the crisis are pointed at Hezbollah, which risks eroding its support base over time. To survive the economic upheaval that has roiled Lebanon for almost two years, the group has been feeding its supporters a steady stream of propaganda, blaming all of the country’s woes on a “financial siege” by the United States, and positioning itself as Lebanon’s would-be savior. But propaganda won’t keep the lights on. To survive with minimal loss of supporters, Hezbollah will have to show that it – and not its foes among the protesters or political opponents – can act, deliver on its promises, and do so responsibly.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox.

Eye on Iran is a news summary from United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI), a section 501(c)(3) organization. Eye on Iran is available to subscribers on a daily basis or weekly basis.