The Wilting of State Department Discourse on Iran Nuclear Deal

The two rhetorical pillars of President Biden’s Iran strategy are a “longer, stronger” deal and “mutual compliance.” The 135 State Department press briefings between January 26 and June 4 reveal that senior officials have uttered these two phrases more than 100 times.

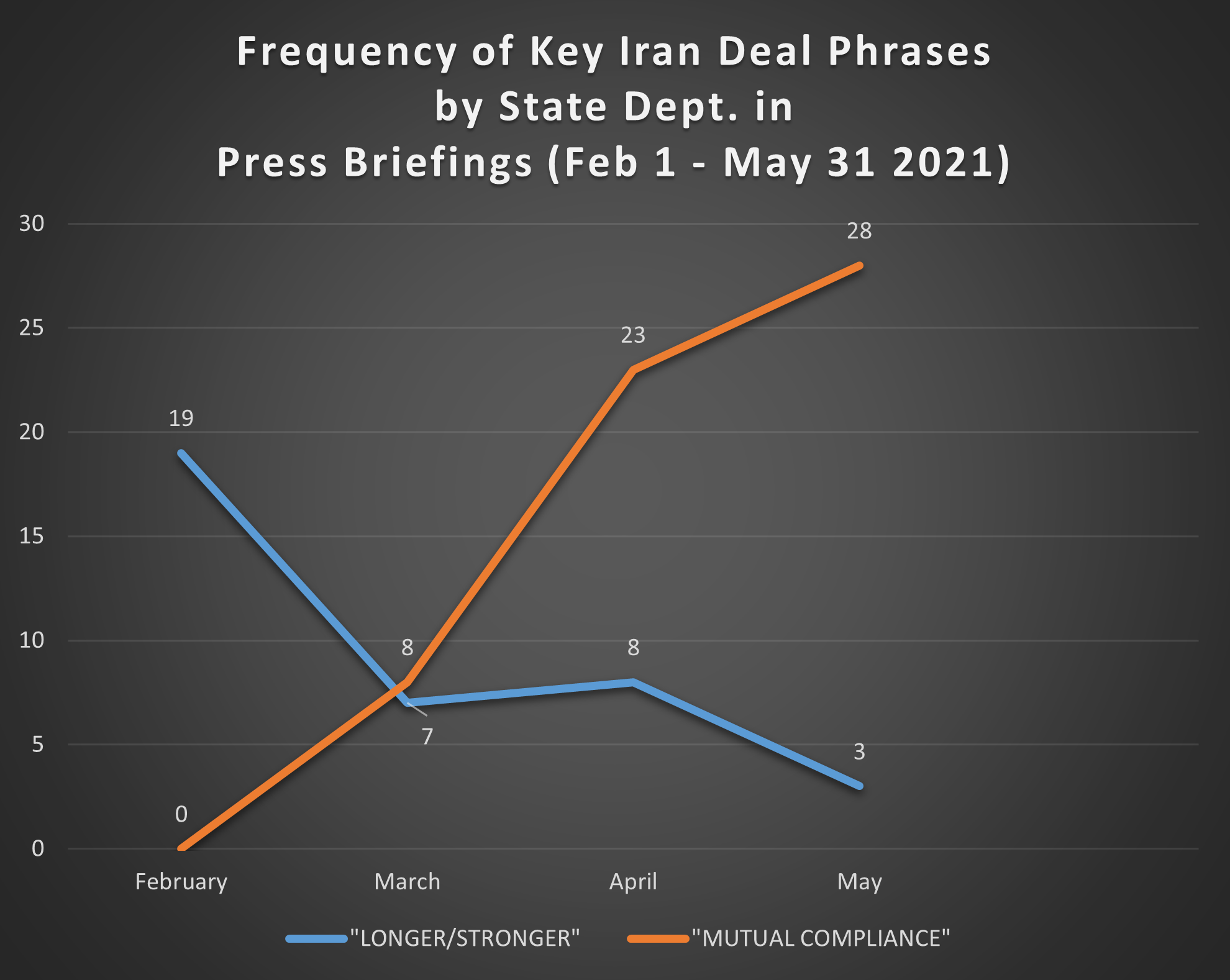

However, in the same period “longer/stronger” mentions have nosedived while “mutual compliance” mentions have soared:

- In the first 33 days (January 26 – February 28):

- “longer/stronger” was mentioned 20 times

- “mutual compliance” was mentioned 0 (zero) times

- In the last 33 days ( May 1 - June 4):

- “longer/stronger” was mentioned 4 times.

- “mutual compliance” was mentioned 34 times

The waning of longer/stronger versus the waxing of mutual compliance is shown here:

Longer, stronger

In February, State Department officials affirmed Joe Biden’s campaign pledge to get a “longer, stronger” deal no less than 20 times, calming the worst fears of JCPOA skeptics.

A “stronger” deal would entail a broader JCPOA 2.0 to address “other areas of concern” neglected in the original deal. “We all know them,” affirmed State Department Spokesman Ned Price on February 2, “ballistic missiles, support for proxies; a number of other issues are included in that.”

While the “longer” part of the equation has never been defined, any significant extension would again provide at least some comfort to JCPOA skeptics alarmed by the fact the current arrangement lifts all restrictions by 2031. As it stands, Tehran has a 10 year glide-path, when it will be completely free to produce uranium to weapons-grade with the full ‘sunsetting’ of the JCPOA.

But as noted, the use of this phrasing has plummeted.

Mutual Compliance

While “longer, stronger” was February’s mantra, the phrase “mutual compliance” did not appear once during that month. Its first mention occurred on March 1.

Prior to then, the formula for JCPOA reentry was articulated in quite different terms. Critically it was Tehran that would be required to go first. This was unequivocal.

“If Iran comes back into full compliance with its obligations under the JCPOA,” stated Ned Price (emphasis added), “the United States would do the same…” He reiterated on the same day “the proposition on the table – as President Biden has said – is that if Iran resumes full compliance with the JCPOA, we will be prepared to do so.”

Likewise, Secretary Blinken stressed that the ball was in Iran’s court, since “Iran is out of compliance on a number of fronts. And it would take some time, should it make the decision to do so, for it to come back into compliance in time for us then to assess whether it was meeting its obligations.”

However, three months later, on May 5, this “hardball” formula explicitly softened into the notion that both Iran and the U.S. would need to “come in to compliance.” The onus was no longer exclusively on Iran to go first. Today, the expressed formula is for Iran and the U.S. to come to some kind of synchronized arrangement.

What does it mean?

This rhetorical 5-month swing, from emphasizing a longer, stronger deal to emphasizing mutual compliance, tracks a worrying shift in U.S. negotiating strategy.

“Longer, stronger” made sense when the full weight of existing U.S. sanctions pressure built up since President Trump’s 2018 withdrawal remained on the table. However, once “mutual compliance” entered State’s lexicon – signaling an American willingness to lift the bulk of those sanctions -- it became increasingly implausible that a better deal could really be achieved.

The shift suggests that the U.S. is no longer bullish about improving on the original deal and has already accepted a lowering of the bar. It suggests that the U.S. is willing to make further gestures and concessions even in the face of escalating Iranian provocations and violations. And it suggests, despite the early tough rhetoric, that the U.S. is set to make another bad deal with the Iranian regime.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox.

Eye on Iran is a news summary from United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI), a section 501(c)(3) organization. Eye on Iran is available to subscribers on a daily basis or weekly basis.