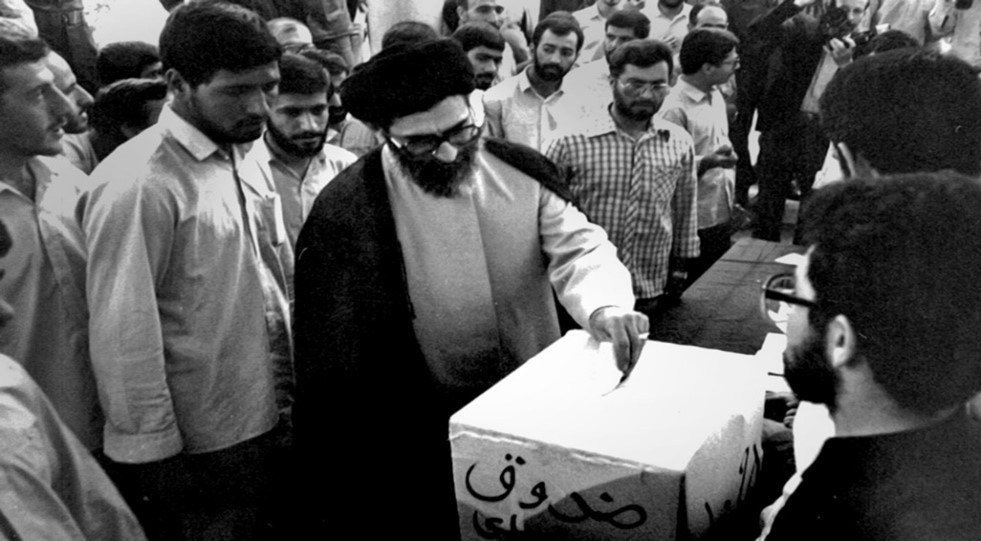

In August 1985, President Ali Khamenei handily won reelection for a second term, prevailing over two other IRP candidates permitted to run with 85 percent of the vote. Immediately following his successful reelection bid, Khamenei’s first order of business was an ill-fated attempt to sack his rival Mousavi, which touched off the largest political crisis in Iran since the removal of Banisadr four years prior.

Frustrated by his lack of power relative to Mousavi and Rafsanjani and by the ongoing political gridlock engendered by the clash between the Islamic Left-dominated majles and conservative-controlled Guardian Council, Khamenei’s animus toward Mousavi rose to the fore. According to Khamenei’s official biography, his dissatisfaction over differences of opinion and the futility of his working relationship with Mousavi was so vexing that he was unwilling to run for a second presidential term and only did so after Ayatollah Khomeini insisted it was his religious obligation.

Khamenei was typically a loyal and obsequious follower of Ayatollah Khomeini. However, his efforts to remove Mousavi were a rare instance of Khamenei asserting his interests and challenging Khomeini’s absolute authority. Rafsanjani’s contemporaneous diaries shed considerable light on Khamenei’s machinations to remove Mousavi. In the days leading up to the election, in which Khamenei’s victory was all but assured, Khamenei enlisted Rafsanjani to query Ayatollah Khomeini over whether he would support Khamenei in selecting someone other than Mousavi to take over as prime minister. From the onset, Khomeini rejected Khamenei’s request, but Khamenei continued to press the matter, urging Rafsanjani to use his influence to change the Imam’s mind. After Khomeini rejected a follow-up request from Rafsanjani, Khamenei upped the ante, issuing a public statement that he would appoint Mousavi to a second term “only if the Imam orders it.”

Imam Khomeini sought to appear above the fray, so he refused to give an official decree mandating Mousavi’s continuance in the role but expressed his opinion that Mousavi should not be replaced. At the inauguration of his second term, Khamenei defiantly spoke out against Mousavi, but the issue remained deadlocked. Rafsanjani continued to mediate behind the scenes, imploring Khomeini to issue a decree supporting Mousavi. However, Khomeini would not relent, although he reportedly remarked in one such meeting, “As a citizen, I pronounce that choosing anybody besides [Mousavi] is treason to Islam.” Khomeini’s statement made clear that Khamenei would be torpedoing his career were he to replace Mousavi. Khamenei finally relented and reappointed Mousavi as prime minister in October 1985.

In a rare show of defiance against the Imam, 99 majles members voted against Mousavi’s reappointment, although Khomeini’s backing of Mousavi was well known, and Khamenei himself later publicly declared he was among those who voted against Mousavi. The crisis led to further tensions between the Islamic Left and conservative factions, poisoning relations between the two sides for the duration of Khamenei’s second term. Khamenei continued to speak out publicly against Mousavi, which irked Khomeini and prompted his son and chief of staff, Ahmad, to intercede on his behalf to implore Khamenei to rein in his criticism, which he did to an extent.

During his second term, Khamenei sought to sideline Mousavi wherever possible and began to carve out a more assertive role for himself where he could, especially in foreign policy. Khamenei’s approach to foreign policy during this period centered on two main imperatives, the first being more traditional diplomacy to establish and broaden relations with non-Western aligned nations to ward off diplomatic isolation, bolster its economy, and secure materiel for the ongoing conflict with Iraq. He traveled to Pakistan, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Angola, Mozambique, Yugoslavia, Romania, China, and North Korea to represent the Islamic Republic of Iran’s government. Khamenei’s secondary foreign policy goal was to spread Iran’s Islamic Revolution and establish Iran’s standing as the leader of the Muslim world. To that end, he focused on bolstering Shi’a political and militant movements around the Middle East and Afghanistan and improving their coordination so these groups could build pockets of Iranian political influence and undertake subversive activities to further Iran’s foreign policy objectives.

Khamenei’s increasing presence and assertiveness on the world stage helped elevate his gravitas and public profile within Iran, which undoubtedly contributed to his ultimate ascension to the Supreme Leadership. In February 1986, Iran achieved a breakthrough in the war with Iraq, capturing and then holding the Faw peninsula in Southeastern Iraq, giving Iran its first major strategic foothold in Iraqi territory and cutting off Iraq’s sole access point to the Persian Gulf. The Iranian capture of Faw sent shockwaves through the Arab world, as it appeared that Saddam was in true danger of losing the war, giving Iranian morale a heavy boost. Saddam abandoned any pretensions of leading the Arab world or establishing dominance over the Gulf region. Instead, he began maneuvering desperately for peace with Iran, insisting on the continued survival of his regime as his only condition for peace. Iran, however, continued to insist on Saddam’s removal, even though subsequent offensives bogged down and the war again stalemated. Still, Iran remained in the driver’s seat so long as it retained control over Faw.

With the tide of the war seemingly turned in Iran’s favor, the high point for establishing Khamenei’s foreign policy bona fides and cementing his stature as a representative of Iran’s revolutionary worldview came in September 1987, when he traveled to the U.S. for the first and only time in his life to address the U.N. General Assembly in New York City. Khamenei’s speech aimed to legitimize the Islamic Republic as a part of the international community, despite its isolation and the efforts of the U.N. to impose sanctions on its government.

Khamenei gave a fiery speech intended as much for domestic consumption – by Iran’s citizenry and revolutionary leadership – as it was for the assembled heads of state. The speech came shortly after the U.N. had proposed Resolution 598, calling for an end to the Iran-Iraq War. In a speech preceding Khamenei’s, U.S. President Ronald Reagan demanded Iran accede to a ceasefire or face further sanctions enforcement actions by the U.N. Security Council. Khamenei began his speech with a religious sermon outlining the basis for Iran’s theocracy predicated on Ayatollah Khomeini’s revolutionary interpretation of Islamic doctrine and culture. He then laid out how the forces of global arrogance – a term referring to the U.S. and its Western allies – had sought to dominate Iran by imposing the Shah’s reign and then fought against the Islamic Revolution, as it represented hope for Muslim and other non-aligned countries to chart a course of independence free of Western domination, corruption, and oppression.

After laying out a litany of Western abuses of Iran and the Islamic world more broadly, including fueling the domestic MEK-led insurgency, Khamenei turned his focus to the “imposed” war with Iraq, a continuation of Western efforts to suppress the Islamic Revolution. While the war was still bogged down, Khamenei maintained Iran’s hardline, insisting that it would not accept any ceasefire that did not meet the condition of labeling Iraq as the aggressor and punishing Saddam Hussein accordingly, as only then would there be a just solution to the conflict that could bring about a lasting peace between Iran and Iraq. He then issued an indictment of the international order more broadly, framing the war with Iraq as one of many conflicts, including the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and the American invasions of Libya and Grenada, where hegemonic powers sought to dominate and subjugate weaker, independent liberation movements.

Khamenei called for a reformation of the U.N. system, particularly attacking the veto power and permanence of the five Security Council powers in favor of a multipolar system predicated on non-interference in smaller nations’ affairs. “Our message to all Third World peoples and governments and to the peoples whose governments have created the order of domination is that the world must not tolerate this abnormal situation any longer. Everybody should tell the superpowers and powerful governments to stay within their own borders and leave the world to the people of the world: you are not their guardian,” exhorted Khamenei. He went on to call upon the Third World to unify and collaborate in self-defense against the immorality and ideological corruption of the world’s major powers.

Khamenei’s incendiary speech triggered the American and Israeli delegations to walk out in protest, a fact that he wore as a badge of honor and assurance of the correctness of his worldview. Following his return to Iran, he organized a week of “National Mobilization Against U.S. Aggression” to further inculcate a spirit of resistance among the Iranian citizenry. Nevertheless, despite the triumphalism of his U.N. address, public sentiment in Iran continued to turn against the futility of prosecuting the Iran-Iraq War in the months after the speech, and revolutionary fervor ebbed.

After losing the Faw Peninsula and with his pleas for peace continually rebuffed by Khomeini, Saddam Hussein concluded that his best chance for the survival of his regime was to increase Iranian suffering. He escalated the tanker war and the war of the cities, attacking strategic energy and economic targets, carrying out aerial bombardments, and launching SCUD-B missiles against major population centers. Iraqi forces also became increasingly brazen in using chemical weapons to repel Iranian offenses. Western powers, who regarded Saddam’s regime as a critical bulwark against the spread of Iranian-inspired Islamist fundamentalism, did not take actions to prevent their use.

Iran miscalculated its retaliations in the tanker war, particularly by targeting Kuwaiti ships due to their support for Iraq. It prompted the U.S. to reflag Kuwaiti ships as American and provide naval escorts for Kuwaiti maritime traffic in the Gulf. This direct American military involvement alarmed Iranian military leaders, forcing Iran to tread cautiously to avoid triggering a muscular U.S. intervention. As a result, Iraq could attack Iranian shipping with near impunity and without reprisals.

The ongoing economic privations and the futility and brutality of the conflict’s combat and heavy losses dampened revolutionary morale. Iran faced the depletion of its reserves, and there was no longer a fresh supply of willing recruits to replenish the basij’s ranks, rendering the human wave strategy unsustainable. Iraq, buoyed by increased intelligence cooperation with the U.S., was reenergized and retook the offensive to reclaim its territory captured by Iran in the Spring of 1988. In a matter of weeks, Iraq recaptured the Faw Peninsula and dislodged Iran from positions around Basra and Majnun Island, rapidly reversing years of hard-fought Iranian gains.

With the tide of the war turned decisively against Iran, continuing the conflict risked outright humiliating defeat, which would imperil the entire Islamic Revolutionary project. By early 1988, Iran’s leading military and political decision-makers increasingly agreed that Iran needed to extricate itself from the conflict. However, Khomeini, who by this time was seriously ailing, remained steadfast in his determination to carry on. Behind the scenes, factional squabbling continued as leaders from the Islamic left and right sought to blame each other for the war's failures. In one telling episode, President Khamenei sought to downplay his responsibility for any shortcomings by arguing that he was powerless within the Iranian political system. He reportedly told a gathering of IRGC commanders in Ahvaz, “Since responsibility for the government does not rest with me but with the prime minister, I am not responsible for the war and the government’s actions...I do not approve of Mir Hossein Mousavi. I accepted him because the Imam ordered it.”

In June 1988, Khomeini appointed Rafsanjani, who had throughout the conflict been the most prominent proponent for continuing the war, as commander-in-chief of the armed forces. This was a last-ditch effort for Iran to reshuffle its military apparatus and an implicit rebuke of IRGC commander Mohsen Rezaei and other military leaders for failing to deliver victory. Khomeini called on Rafsanjani to restore unified command and facilitate greater coordination between the IRGC and the conventional military, which had broken down throughout the conflict. In his decree appointing Rafsanjani, Khomeini said, “I call on the dear people of Iran and the armed forces and security forces to stand steadfast, with revolutionary patience and endurance and with strength and resistance, in the face of the plots of global arrogance, and to be certain that victory belongs to those who are patient. Today’s world is saturated with injustice and treachery and you, the true followers of Islam, are at the height of purity and honor.” Khomeini’s words showed that despite, or perhaps because of, all the costs Iran had sunk into prosecuting the war, he saw continuing the war to victory as essential to the survival of his Islamic Revolution, and he was accordingly prepared to continue devoting lives and resources to his quixotic quest.

By the time he took over as commander-in-chief, Rafsanjani had developed a pragmatic streak that would define him. He recognized that exiting the war was vital for the Islamic Republic’s continued survival. While not outright calling for an end to hostilities, he maneuvered behind the scenes to build the case to Khomeini that Iran could not continue. He gathered assessments from top military leadership on the state of their forces and what it would take to regain the upper hand and pursue victory. IRGC commander Mohsen Rezaei gave a particularly bleak assessment, saying it would take at least five years and require extensive procurement efforts, which were all but impossible due to sanctions, to refurbish the IRGC and have any hope for an Iranian victory.

On July 3, 1988, the U.S. Navy mistook an Iranian civilian airliner for a military aircraft and shot it down, killing all 290 passengers. Although accidental, the incident hammered home to Khomeini and the final clerical holdouts that the U.S. and other forces of “global arrogance” would stop at nothing to deny victory to the Islamic Republic. Israeli historian Efraim Karsh wrote in his analysis of the Iran-Iraq War that the incident “provided the moral cover of martyrdom and suffering in the face of an unjust superior force that allowed the regime to camouflage the comprehensive defeat of its international vision.”

Khomeini finally recognized that continuing the war was imperiling, rather than keeping alive, the Islamic Revolution and decided to accept U.N. Resolution 598 without conditions. In so doing, he prioritized regime survival over fervent adherence to revolutionary principles. President Khamenei sent Iran’s official acceptance of a ceasefire to the U.N. Secretary-General on July 17, 1988, stating, “We have decided to declare officially that the Islamic Republic of Iran – because of the importance it attaches to saving the lives of human beings and the establishment of justice and regional and international peace and security – accepts UN Resolution 598.”

In a letter to the Iranian leadership and public, Ayatollah Khomeini cited Mousavi’s assessments that the war had drained the country’s coffers and Rezaei’s analysis that victory could not be attained for at least five years without extensive procurement as the reasons he took the “bitter decision” to end the war. Khomeini concluded his letter, “You dear ones, more than anyone else, know that this decision is like drinking the poisoned chalice and I submit to the Almighty’s will and for the safeguarding of Islam and the protection of the Islamic Republic, I do away with my honour. O’ God! We rose for the sake of your religion, we fought for your religion and we accept the cease-fire for the protection of your religion. O’ God! You are aware that we do not collude even for a moment with America, the Soviet Union and other global powers, and that we consider collusion with superpowers and other powers as turning our back on Islamic principles. You are aware that, the high-ranking officials of the system have taken this decision with extreme sadness and with their heart filled to the brim with love for Islam and our Islamic country.” While the outcome did not deliver the victory they had sought, Khomeini and Iran’s leadership framed the end of the war as a triumph of sorts since Iran, a fledgling power, had withstood the efforts of the U.S. and other superpowers to vanquish the Islamic Revolution.

Although it ultimately suffered defeat, the IRGC and basij emerged from the conflict as battle-hardened forces whose ideological commitments to the Imam and the Islamic Revolution never wavered. There was a brief debate on the role of the IRGC going forward, as their peacetime role was not clearly defined. Iran’s clerical leadership considered folding the group into the regular armed forces and assigning them to defend the nation’s borders. However, ultimately, the Khomeinists saw their ideological fervency and vast human resources as too valuable a tool to give up. The IRGC was kept intact and given peace-time religious and national service missions, including construction and engineering roles in rebuilding the country. This helped the IRGC take on an outsized role in Iranian non-military and economic affairs, which also translated into greater political power.

The end of the Iran-Iraq War ushered in a period of uncertainty over the future direction of the country and the revolution. For eight years, the war had destroyed Iran’s infrastructure, ravaged its economy, and led to hundreds of thousands of Iranian deaths. However, despite hardships, it also served to unify much of the country behind the Khomeinist movement. In the immediate term, Iran’s most pressing priority was rebuilding its military and energy sector. This necessitated Iran modifying its “neither East, nor West” ethos, and in the months after the war, Iran set about reestablishing diplomatic and trade ties with the Soviet Union, Canada, the UK, France, and West Germany. Because of the sectarian nature of its war with a leading Sunni-led power, the luster of the Islamic Revolution was dulled in the Sunni Arab world. Except for Lebanon, where Iranian-inspired Amal and Hezbollah wielded significant influence, it appeared the threat of the export of the revolution had receded, and the Khomeinists would have to be content with an Islamic Revolution simply within Iranian borders.