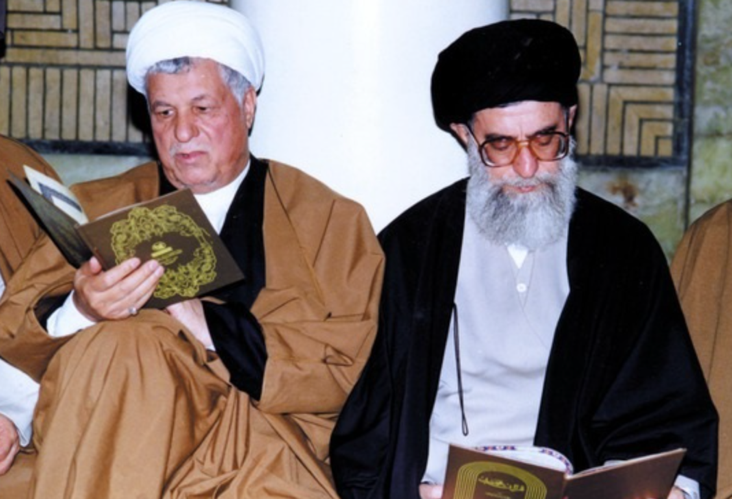

As he set forth on his mission to rebuild Iran and prop up its failing economy, Rafsanjani appointed a cabinet primarily comprised of technocrats loyal to him, with Khamenei opting not to use his veto power over Rafsanjani’s selections. Rafsanjani saw the need for Iran to tamp down on its revolutionary extremism to rebuild speedily and exhorted that Iran “cannot build dams with slogans.” While Khamenei remained publicly committed to the extremism of the Islamic Revolution and continued his fiery rhetoric, he nevertheless gave Rafsanjani the backing he needed to carry out his agenda. Khamenei’s idealistic extremism gave the impression of tensions between his worldview and Rafsanjani’s pragmatic commitment to technocratic nation-building, but in reality, Khamenei’s style complemented Rafsanjani’s, assuaging his most hardcore revolutionary supporters without preventing Iran from rebranding as a more moderate, responsible actor on the world stage. This good-cop, bad-cop dynamic would repeatedly serve Iran, convincing Western audiences that Khamenei was playing to his base and that it was necessary to cooperate with and appease Iran to empower more moderate forces in the Islamic Republic’s government.

While Khamenei lacked the power to marginalize Rafsanjani and Iran desperately needed rebuilding, Khamenei put aside his hardline disposition and worked cooperatively. President Rafsanjani’s signature initiative inaugurated a five-year development plan, which could not have been done without the Supreme Leader’s acquiescence. With Iran’s currency reserves depleted, Rafsanjani led Iran through a series of structural reforms to reorient Iran as a market economy and secure needed International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank loans. Rafsanjani’s measures aligned with these institutions’ best practices and included reopening the Tehran stock exchange, cutting government subsidies, raising taxes, devaluing the national currency, promoting trade liberalization and increasing exports, and privatizing nationalized industries. In addition to economic liberalization, Rafsanjani relaxed social and cultural controls as well, and the government largely tolerated women wearing brightly colored veils and makeup, public socialization between the sexes, the proliferation of banned satellite dishes, and the flourishing of the arts, as well as literary and intellectual journals. Rafsanjani’s Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance, Mohammad Khatami, who would succeed him as president, oversaw much of the social reforms during this period.

Rafsanjani’s reforms were largely intended to coopt the bourgeoisie, giving them new chances to profit and become consumers. Whereas Ayatollah Khomeini had called on Iranians to sacrifice and embrace asceticism to meet the revolutionary demands of the war with Iraq, Rafsanjani justified the bazaaris flooding Iran with imported products and the creation of a consumerist ethic, stating, “Why should you forbid yourself things that God made permissible?... God’s blessing is for the people and the believers. Asceticism and disuse of holy consumption will create deprivation and a lack of drive to produce, work and develop.”

While Rafsanjani’s embrace of neoliberal reforms stimulated economic growth, the benefits tended to accrue to the wealthy and well-connected, increasing the gap between the rich and the rest of society. The middle and lower class were also negatively affected by increased taxes and the cutting of subsidies. However, efforts at privatization were plagued by endemic corruption, as the spoils went primarily to elites with whom Khamenei and Rafsanjani sought to cultivate patronage links. This need for patronage links served to hamstring Iran’s development and curtail widespread privatization, which led to the state retaining a central role in the economy. The more market-oriented Rafsanjani had set a goal of reducing the sector by 8 percent, but it instead grew by 3 percent during the early 1990s, driven by the IRGC and the labyrinthine system of bonyads taking over the operation of numerous semi-public enterprises.

Rafsanjani’s family benefited tremendously from the regime’s corruption, building up an opaque network of foundations and front companies. The family’s holdings included Iran’s largest copper mine, a company that dominated Iran’s lucrative pistachio export sector, an oil engineering firm, and an automobile factory. Rafsanjani’s relatives were also selected for key politically advantageous posts, including the provincial governor of Kerman province, positions in the oil ministry, and director of Iran’s main state-owned TV network. The vast wealth accrued by his family buttressed Rafsanjani’s political power but also created vulnerabilities that Khamenei would exploit as part of his politically expedient crackdown on corruption when his relationship with Rafsanjani soured.

During Rafsanjani’s initial five-year development plan, the IRGC came to take on an outsized role in Iran’s economy. Initially, Khamenei and Rafsanjani were concerned with the IRGC encroaching into the political realm. They sought to make them an economic powerhouse to bribe them to constrain their political ambitions effectively. Khamenei signed off on transforming the IRGC’s engineering corps, which had been primarily engaged in the rapid construction of fortifications and bridges during the war, into a megalith construction consortium known as Khatam Al-Anbiya (KAA). KAA was given a virtual monopoly on projects related to Iran’s reconstruction, including revamping oil and gas infrastructure and constructing dams, roads, tunnels, and water transfer projects. In addition to co-opting the IRGC’s top brass, KAA served as a jobs program for thousands of IRGC conscripts who had returned from the frontlines with scant employment prospects, ensuring their loyalty to the regime. The IRGC framed its transition of spearheading Iran’s development and entering the economic realm as the continuation of its revolutionary mission to ensure the supremacy of the Islamic Revolution over Western cultural encroachment and imperialism. Iran’s economic modernization became the frontline of a new holy mission, as Iran’s development into an economic powerhouse would serve as a rebuke to the U.S.’s desire to weaken or replace the revolutionary regime.

Khamenei and his traditionalist backers chafed against some social reforms during this period. Likewise, the bazaari constituency aligned with Khamenei’s emerging coalition opposed some aspects of Rafsanjani’s industrialization-focused economic agenda, as modern trade centers threatened their more traditional informal mercantilism. Regardless, Khamenei maintained his alliance with Rafsanjani primarily to marginalize the Islamic left. Whereas Khomeini sought to balance the right and left factions, Khamenei has sought to dominate the left wherever possible. However, he has proven adept at providing the left space to operate when backed into a corner. Through its control of the majles, the main lever of power available to it at the time, the Islamic Left sought to hamstring Rafsanjani’s economic agenda, which they saw as contributing to the spread of corruption and rising inequality. The Islamic Left’s opposition threatened to derail Rafsanjani’s transformative economic agenda and suggested political instability, which imperiled foreign trade and investment inflows.

While the early Rafsanjani years sparked optimism for economic and social liberalization, the specter of infighting and instability made political liberalization unpalatable. Working through the Islamic Republican system, Khamenei and Rafsanjani conspired to neutralize the left. In the 1992 majles elections, Khamenei endorsed the Guardian Council’s decision to disqualify nearly 1,000 candidates, predominantly on the left, including many prominent sitting members of parliament. Speaker Mehdi Karroubi was among those banned from running. The left decried these summary disqualifications as signs of an emergent dictatorship but was powerless to prevent them. Those on the left who did stand for election did not fare well given the broad-based support for Rafsanjani’s agenda, and only 20 percent of incumbents retained their seats as conservatives and pragmatists came to fully dominate the majles, with the hardliners as the most numerous faction. Karroubi was replaced as majles speaker by a hardline Khamenei backer, Ali Akbar Nateq Nuri.