Proscribing the IRGC: Whitehall vs. Westminster

Since the killing of Mahsa (Jina) Amina on September 17, 2022, no fewer than 55 British parliamentarians have called for the proscription of the IRGC. In the same six-month period, there have been just under 200 references to the IRGC during parliamentary debates. At the current tempo, the IRGC (or “Revolutionary Guard(s)”) will have been cited more times in a single year than in the preceding 43 and a half years since its founding in 1979 (342 references). Evidently this is not going away (much like the IRGC itself) and, despite powerful counter-forces, Whitehall will find it increasingly difficult to deny Westminster.

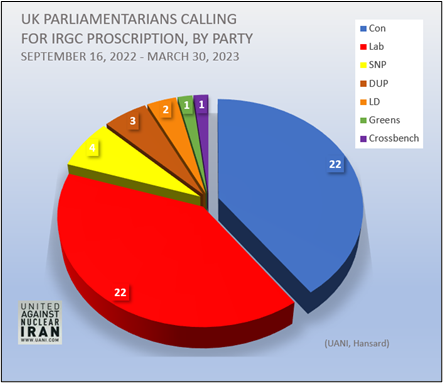

The plea is clear, consistent, and equally distributed across party lines. MPs typically at variance on every other issue – former Tory leader Sir Iain Duncan Smith and Labour’s shadow foreign secretary David Lammy make unusual bed-fellows – are here united. Outside the two main factions, minority party MPs from the Liberal Democrats, Scottish Nationalist Party (SNP), and Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) have all echoed the call.

It is also endorsed in the Upper House, usually characterized by a measured approach consonant with its primary power to delay legislation. The Lords, in particular Lords Polak (Conservative) and Coaker (Labour), have been as explicit as their Commons counterparts in the plea to add the IRGC to the list of 78 groups already banned under the Terrorism Act 2000. Also common to both Houses is a repeated demand for government action without further delay. The sense of urgency is only heightened by the fact that the present, limited sanctions on the group will expire in 7 months. “We need to act now,” noted Alicia Kearns, “if we are to make sure that, in October, we do not end up with the IRGC no longer being sanctioned by the British Government.”

It would be an understatement to say such unity is unusual. In fact it is difficult to think of many topics in British politics perhaps outside of the National Health Service that have inspired such resounding cross-party, cross-chamber consensus.

Still the Government vacillates, with a stock response that while sympathizing with the general sentiment, it “does not preview” potential sanctions.

More candidly, many believe the Foreign Office is to blame for the stoppage. Last month, Labour’s Lord Coaker bluntly stated “there is a real problem at the heart of government because the Foreign Office is blocking what the Home Office wants to do,” specifying that “the core of it” is a reluctance to designate a government agency as a terrorist organization.

Others hold responsible the U.S. State Department, which has reportedly “argued that the UK can play a key role as interlocutors with Tehran that would be undercut by the designation.” This would perhaps explain the several tepid State Department responses in press briefings to the idea that Britain follow U.S. policy and explicitly proscribe the IRGC. The Foreign Office has seemingly expressed similar reservations about a consequent loss of “access,” which “could harm British interests.”

Regardless of the source, both arguments are feeble. Semantics do not and should not outweigh the fact that, as Lord Polak stressed, “Hezbollah and Hamas, which we all proscribed, are in fact the unruly children of the parent body—the IRGC, which needs to be proscribed.” Moreover, the opposition Labour Party has already provided an obvious remedy to assuage Whitehall mandarins, having affirmed it “would proscribe the IRGC, either by using existing terrorism legislation or by creating a new process of proscription for hostile state actors.” Likewise, the UK’s supposedly helpful position as “interlocutor” is another canard: “access” to the regime proved utterly ineffectual in stopping the Islamic Republic’s execution of British national Alireza Akbari on January 14, in spite of thunderous demands from both the Prime Minister Sunak and his Foreign Secretary James Cleverly.

In a Guardian oped in December, Cleverly wrote that Britain had “regained the power to impose independent national sanctions” following Brexit, with a chance to “act swiftly and robustly.” Nowhere is there so great an opportunity to put these fine words into action than in the blacklisting of the IRGC, a rare policy decision that would enjoy overwhelming political support.

Receive Iran News in Your Inbox.

Eye on Iran is a news summary from United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI), a section 501(c)(3) organization. Eye on Iran is available to subscribers on a daily basis or weekly basis.